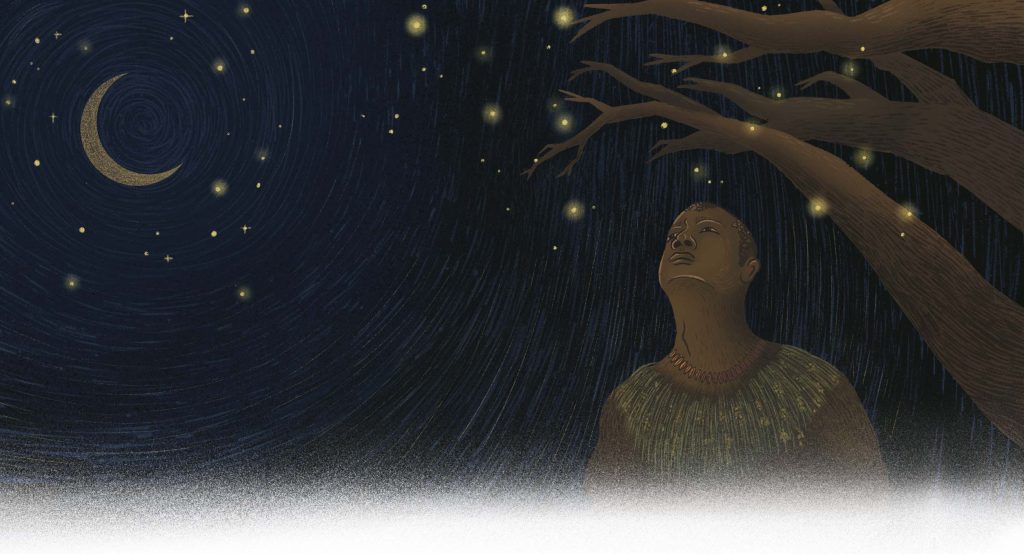

I am the last born and I have a long following/ Everything and everyone is my elder/

I move through the relatives in my green leaves/ I eat canoes and drink inlets…

(from Maori writer Hinemoana Baker’s 2008 poem Last Born)

At the beginning of the Bhagavad Gita, seven war conches are named as their owners sound them at the start of the climactic Kurukshetra battle. War conches are shankha, the sacred or divine conch that is used in Hindu and Buddhist ritual, and in sacred ceremonies in different saltwater cultures around the world. There is a three to four thousand year tradition of diving to collect shankha from the waters of India and Sri Lanka, including Palk Strait.

The conch seems an unlikely candidate to reach the level of reverence it does in India, Sri Lanka and other cultures. In scientific terms, it is a large marine gastropod, a big sea snail. They are predators, feeding on other marine invertebrates and especially species of sand-living worms. The specific animal revered as shankha is Turbinella pyrum in Latin. It lives on sandy sea bottoms, and is common and restricted to the southern coasts of India, parts of Sri Lanka and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. In its living form it is not obviously attractive, the shell being covered by a dark brown mantle of soft tissue. Once processed, it is a shining white symbol of the divine.

On these coasts on both sides of Palk Strait, the material properties of the living environment of land and ocean continue to be reshaped into the built form of local human beach communities. From the land, palmyra and coconut trunks, stalks and leaves become furniture, fences, roof framing, thatch, fishing boats, paddles, bailers, shade covers, walls. From the sea, sand becomes concrete, shells become lime, coral becomes construction blocks. Local artisans have specially woven the roof thatch on our buildings in both India and Sri Lanka. There are no nails or synthetic materials, and room dimensions are determined by the bearing capacity of palm beams.

But these places are not held in the past. Threaded through these continuities, the persistent materials of modernism are rethought and repurposed, as well as discarded. Polystyrene packing becomes boat hulls, worn fishing nets become all kinds of containers and wrapping, plastic bottles become fishing floats, old clothes become flags and markers. All these same things line the tidemark on beaches. Every turtle skeleton I find is entangled in an indestructible nylon net.

Underwater, the experience changes daily and hourly. The sand is rippled by the tide, pitted and tracked by the activities of hosts of small invertebrates. Tiny fish speed through the mid and upper levels in dense and tightly choreographed shoals. Jellyfish with two metre streams of stinging tentacles drift silently. The calligraphy of tiny lives marked in the sand is layered over with dead and living animals and plants. The hard calcium carbonate of shells, exoskeletons, bones and claws persists while the soft flesh, mantle, muscle and organs are consumed by predator and detrivore.

Like all species, shankha are both eater and eaten. They hunt for the polychaete tube worms in the sand while divers, stingrays and other predators hunt for them. The divers that hunt shanka now are varied in skill levels and access to equipment. Many approaches are used: breath-hold with various equipment, scuba, scuba variants, hookah, and likely more than this as cheap innovation is applied to technologies to get divers underwater. These are all dangerous to different degrees.

The shankha is collected alive, but cannot live out of water, and likely dies while still on the boat. This is the beginning of the shankha’s journey into ritual. The large muscle comprising much of its body is kept for food by some divers, the elements of the living animal diffusing into the muscles of the living diver. The shell is processed into the ceremonial instrument, and its opercula ground into fixative for incense.

The calcium carbonate of the shankha’s exterior shell is shaped inside as a perfect receptacle for its strange yet familiar body. As humans, as vertebrate mammals, we carry the calcium carbonate of our skeletons inside, our bodies vulnerably open to the world, just our brain protected inside bone. When we die, both shankha and humans, the bone or shell parts of our bodies persist after the detrivores have finished with our flesh. Everything living survives through the deaths of others, who are all our/their relatives, close or more distant – we all eat our relatives, evolutionarily speaking, sometimes distant (molluscs, plants) and sometimes closer (mammals). Our interspecies interdependence is based not just in the biology of food but in the biology of evolutionary reproduction: both eating and sex. It is no accident that we recognise that the warm involuted whorls of the shankha reflect the human birth passage, and that both conches and oysters are aphrodisiacs in many cultures. The reproductive processes of all species are implicated and reflected in our own, including the lowly molluscs. Eating oysters increases dopamine that boosts libido, and their high levels of zinc are important for testosterone levels in both men and women. The creative generation of life on Earth endlessly recycles the available constituents on the planet, from the elements to the forms.

More than five hundred million years ago, an impossibly long time to imagine, we shared a common evolutionary ancestor with marine molluscs: our bodies are composed of the same elements, we come from the same ancient World Ocean. Humans do not just share the building blocks of our bodies, but the patterns of composition that put them together. We share this kinship with shankha and everything else living on the planet, as well as innumerable now extinct species, and they share that kinship with us.

For the shankha itself, it lives in a world we can hardly know, the sentient context of Palk Strait. Hindu belief depicts the very rare reverse turning shell, the dakshinavarti shankha, as reverently attended by hundreds of normal spiralled shells on the sea floor. Have human eyes seen this?

For shankha divers there are tactile engagements with the living animal in its underwater world, they earn their connection through skill, effort and knowledge. For people who purchase shankha as an emblem of luck and prosperity, the shining shell functions as a mnemonic, a reminder to embrace and also to transcend the mundane. For the ordained users of shankha in Buddhist and Hindu ritual, and in saltwater cultures around the world, they put the polished shell to their mouths, its shining form an embodiment of the sacred, and its sound calling the divine into presence. The shankha connects us to the universe of the ocean, and the ocean connects us to the origins of all life.