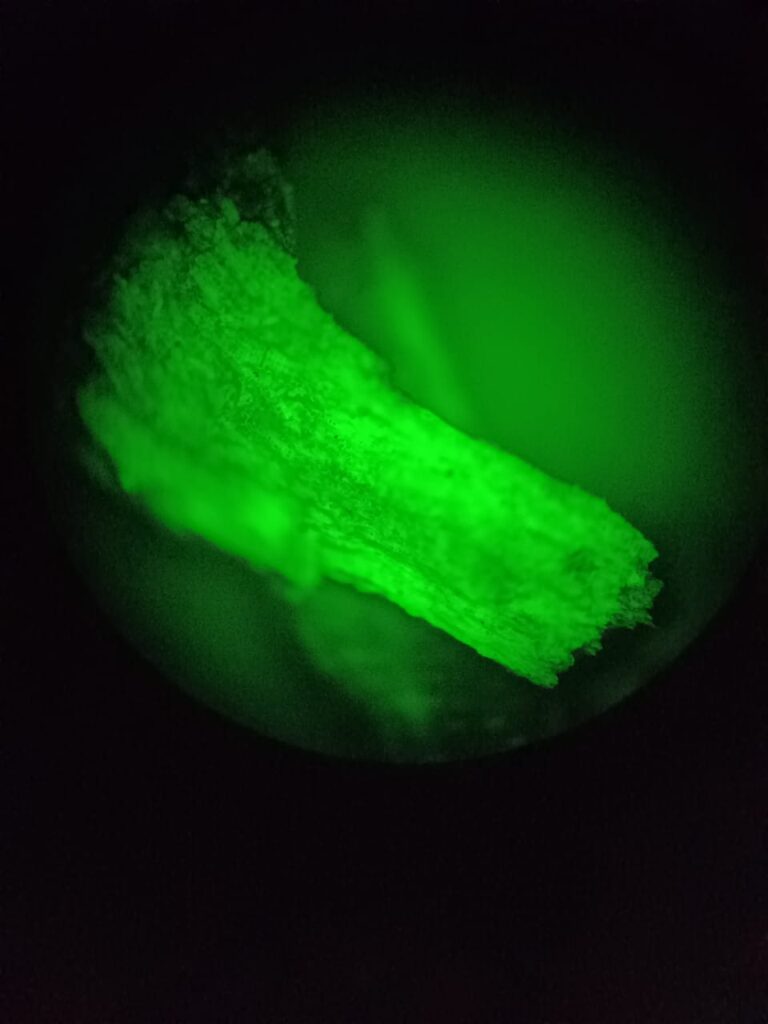

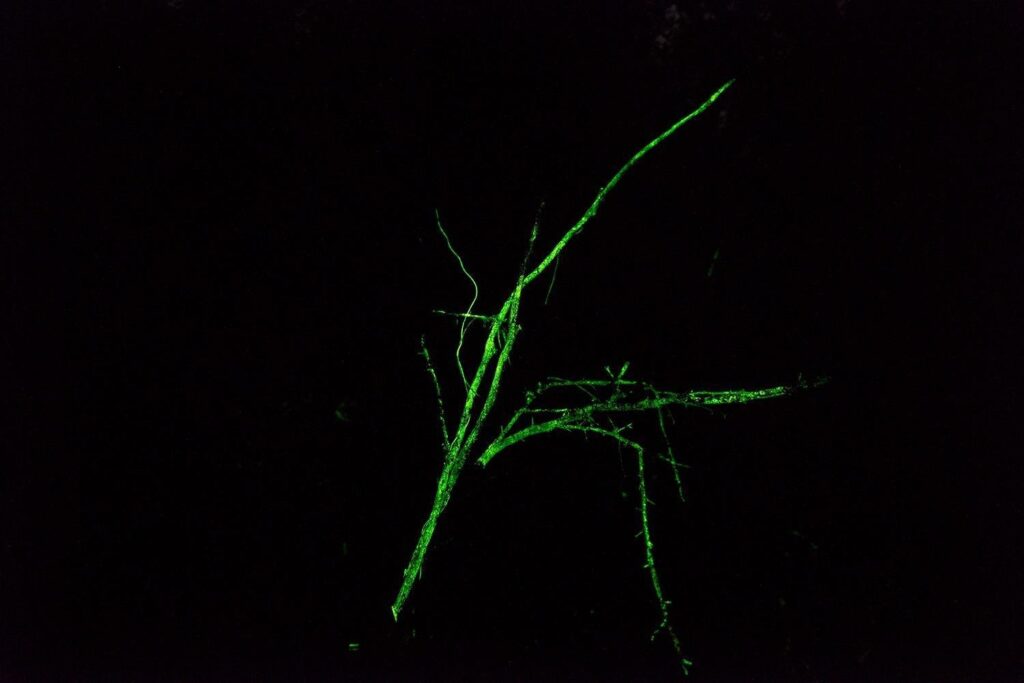

Feature image: Luminous fungi in the forests of Sirsi, where I witnessed this magical phenomenon for the first time (Photo credit: Ashwini Kumar Bhat)

It was August 2020. My father and I were driving home from our ancestral village in Sirsi, located in the Uttara Kannada district in Karnataka, India. As we made our winding way through the forests of the central Western Ghats, the evening turned pitch dark and it started to rain. Suddenly, my father stopped the car in a dense part of the forest.

Cicadas screeched, frogs croaked, and I spotted fireflies. “Observe the trees,” my father said quietly. Minutes passed, and something like a coat of velvet on a leaf started to glow faintly—a teal green colour. In a short while, the entire tree bark was bathed in a soft green light! I was astonished to see it, and picked up a glowing branch fallen on the ground. It looked like a magical wand from a fantasy film or a lightsaber from Star Wars.

And on another tree, there were tiny mushrooms that glowed, different from the fungal mat I first observed. Soon, my eyes adjusted to the darkness, and I noticed that the whole forest floor was lit up. I whipped my phone out to take a photo, but it was invisible to the camera! Thanks to this wondrous encounter, I went down a rabbit hole trying to find out why some fungi evolved to glow.

Biochemistry, not magic

Some organisms, including fireflies, certain species of fungi, jellyfish, phytoplankton, and marine animals, naturally produce light as a result of an internal chemical reaction. In the case of fireflies and bioluminescent fungi, a compound called luciferin emits light when it reacts with oxygen and an enzyme called luciferase. This is referred to as ‘cold light’ because nearly all the energy released by the chemical reaction is converted into light (with an intensity ranging from 500–530 nanometres). Therefore, little to no heat is produced.

Molecular dating has shown that bioluminescent fungi—of which there are about 100 species—are 160 million years old. And they don’t all glow the same. Some have different colours, some glow all day, some have fruiting bodies (mushrooms) that glow, and some glow only at a certain life stage. In India, luminous fungi have been reported during peak monsoon from the Western Ghats across Goa, Kerala, Karnataka, as well as the northeastern states such as Meghalaya. Species include Mycena chlorophos in Goa and Karnataka, and Roridomyces phyllostachydis in Meghalaya.

There are several hypotheses for why fungi glow. It could be part of a circadian rhythm, such as with Neonothopanus gardneri, a species endemic to Brazil that glows brightly only at night. The light could serve to attract nocturnal insects, which then help to disperse fungal spores. This mechanism is reminiscent of the tactic employed by flowering plants to attract pollinators and facilitate seed dispersal. But not all fungi produce fruiting bodies, and many fungi react to darkness rather than the circadian rhythm of night and day.

But regardless of why bioluminescent fungi glow or whether it serves any purpose, they are an integral part of our culture and folklore, mainly as fantastical elements. For example, in my ancestral village, luminous fungi are called Kolli deva, meaning a ghost that holds a torch. In European stories, they are known as foxfire and associated with mischievous spirits in forests. And in The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, a 10th-century Japanese story, a childless bamboo cutter finds a three-inch girl inside a glowing bamboo stalk. She grows rapidly into a beautiful woman, setting impossible tasks for her numerous suitors, before ultimately revealing her celestial origins and returning to her home on the moon.

Fading light

My father, who grew up in our ancestral village, when returning home through the forest at night, sometimes used branches with bioluminescent fungi to light the way, if his torch’s battery was dead. But my grandmother says that these special fungi are rapidly vanishing. Where the whole forest floor once glowed, now it is just a small patch in the forest. According to other local elders, the fungi also don’t glow as brightly as they used to. Even in my own experience, there has been a stark difference from when I observed the fungi with my father in 2020 to the present.

Luminous fungi are often rare and found in specific microclimatic niches. They could, therefore, be bioindicators of a good, healthy forest with adequate rainfall. But these habitats are under threat from deforestation, climate change, and the subsequent extreme variations in rainfall patterns. This is worrying because fungi, in general, are a crucial part of our ecosystems. Several species of bioluminescent fungi are saprophytic, growing and feeding on dead or decaying organic matter such as wood. This makes them important carbon and nutrient recyclers. Thus, conserving luminous fungi includes the conservation of the entire habitat.

So next time, when you are in these forests, switch off every light and wait. You might just see the green glow on the forest floor. For my grandmother, that magic was a lived reality, while for me, it’s a reminder of how quickly such things can disappear. We cannot afford to lose these luminous fungi even before we have had a chance to understand them.

Further Reading

Oliveira, A. G., C. V. Stevani, H. E. Waldenmaier, V. Viviani, J. M. Emerson, J. J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 2015. Circadian control sheds light on fungal bioluminescence. Current Biology 25 (7): 964–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.02.021.

Perry, B. A, D. E Desjardin and C. V Stevani. 2024. Diversity, distribution, and evolution of bioluminescent fungi. Journal of Fungi 11 (1): 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11010019.