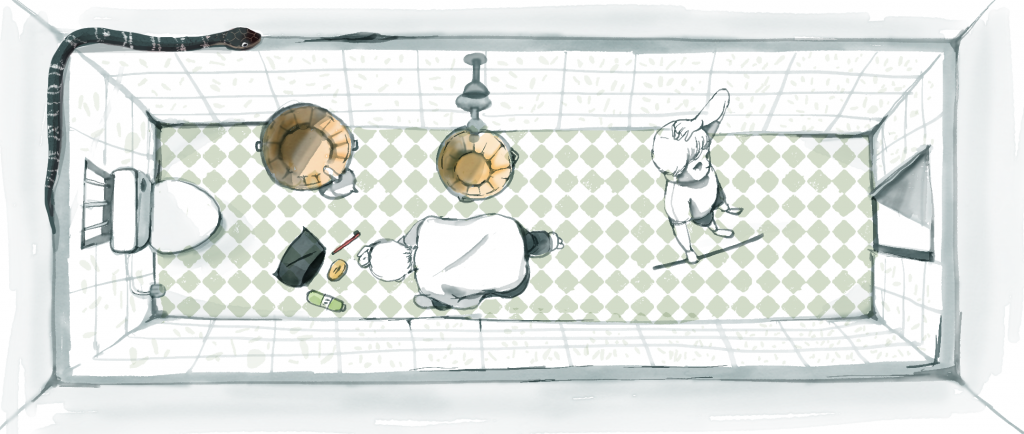

It’s a hot, sticky monsoon afternoon of interviews in the buffer zone of Maharashtra’s Melghat Tiger Reserve. I’m there making maps with people about places they avoid at certain times of day to reduce their chances of encountering dangerous wild animals. Having just completed the day’s last interview, I return to my room, looking forward to a cool, refreshing bath. I throw my notebooks and papers on the bed and go straight to the bathroom, where I place my toiletries on top of the toilet tank, and turn on the shower faucet. I startle as a frog jumps up from the bathroom floor, having just been hit by the tap water. We stare at each other for a few seconds as I ponder whether one can sweep such a creature out of a room with a broom. Then, I hear a thump to my right. I look up and see the rearing head of a small, black snake with thin, white stripes emerging from my toiletry bag.

I quickly back out of the bathroom and call for Bishram, who manages the campus where I am staying. We had come across this snake before—if not the same individual, then one of the same species. To be clear, I am not sure if it is a venomous common krait (Bungarus caeruleus) or the krait’s nonvenomous mimic, the wolf snake (Lycodon aulicus). But when Bishram and I had seen it before, we treated it as if it was a krait, and we thoroughly intend to do the same this time.

Along with the spectacled cobra, Russell’s viper, and saw-scaled viper, the common krait is one of the ‘Big Four’ snakes in India—those responsible for the greatest number of ‘medically significant’ snake bites in India. ‘Medically significant’ is bureaucrat-ese for deadly. Krait venom contains a unique toxin that prevents brain signals associated with muscle movement to pass from one nerve cell to another, causing paralysis. People bitten by common kraits develop a variety of symptoms, which tend to progress from drooping eyelids, weakening eye muscles, abdominal pain, and facial weakness during the first 2–4 hours, to difficulty swallowing, lower limb weakness, and respiratory paralysis after 4–6 hours. Common kraits are nocturnal, and many bites occur when people accidentally roll onto the snake while sleeping on the floor. However, because bites are typically painless, most people do not wake up until they begin experiencing later symptoms. Antivenin can effectively clear venom from the system, but it cannot prevent or reverse neuromuscular paralysis, meaning that people who are bitten often require assisted ventilation in addition to antivenin.

I had researched all this information after Bishram and I first encountered what we thought was a common krait, and it all flashes through my head during this encounter. As I back away from the bathroom, the snake seems to disappear into my toiletry bag, which—like the snake—is black. I lose sight of it before Bishram reaches the bathroom. He arrives with a long bamboo stick, which he uses to carefully lift the bag onto the floor and poke through it. But the snake is not there. Despite further investigation of our surroundings, we cannot find it anywhere in the bathroom, toilet, or outside the window.

Some time goes by, and I discover that frogs can indeed be swept out of a room, but I cannot help but think that something does not add up. I had heard a thump, which suggests that the snake had fallen. But there was nowhere for it to have fallen from—no rafters or ledges in the bathroom at all. Considering it also seemed to have disappeared and no one else saw it, I begin to wonder if anxiety—a side-effect of my anti-malaria medication—had finally gotten the better of me, and that I had imagined the snake altogether. It was not until the following day that we realized what had happened.

After dinner, I hear Bishram calling me back to the bathroom. I quickly join him, and he points at the snake resting on the half-centimeter edge of tile that lines the walls, over seven feet up. Another campus employee, Tiwarilal, who is less afraid of snakes than either myself or Bishram, joins us and tries to lift the snake with the bamboo stick. As it attempts to evade Tiwarilal, the snake reveals its secret. It moves down into an up-until-then unknown gap between the tile and the concrete wall, where it must have escaped to the previous day. Eventually, Tiwarilal goads the snake back up by pouring water into the gap. He lifts it with the bamboo, puts it into a heavy plastic container, and takes it away on his motorcycle to release into the forest far from the campus.

The encounter with the snake changed how I moved and experienced the landscape during my fieldwork. Interviews and map-making could tell me where people think dangerous wildlife might be, and whether people avoid those places. However, these tools could not help me understand how wildlife encounters shape the way people experience the landscape. Having encountered snakes before, and being particularly eager to avoid them as a result of my medication-induced anxiety, I had always been cautious about where I stepped, especially when walking at night or off the main road. But until this encounter, I had never considered that I should also look up when trying to avoid snakes. From then on, I always looked both up in the trees and on the ground when walking in the forest, and always checked the rafters and the floor when entering a room. This is not to say that others perceive risks from wildlife in a similar way, but that from encounters with wildlife emerge new ways of seeing and experiencing landscapes.