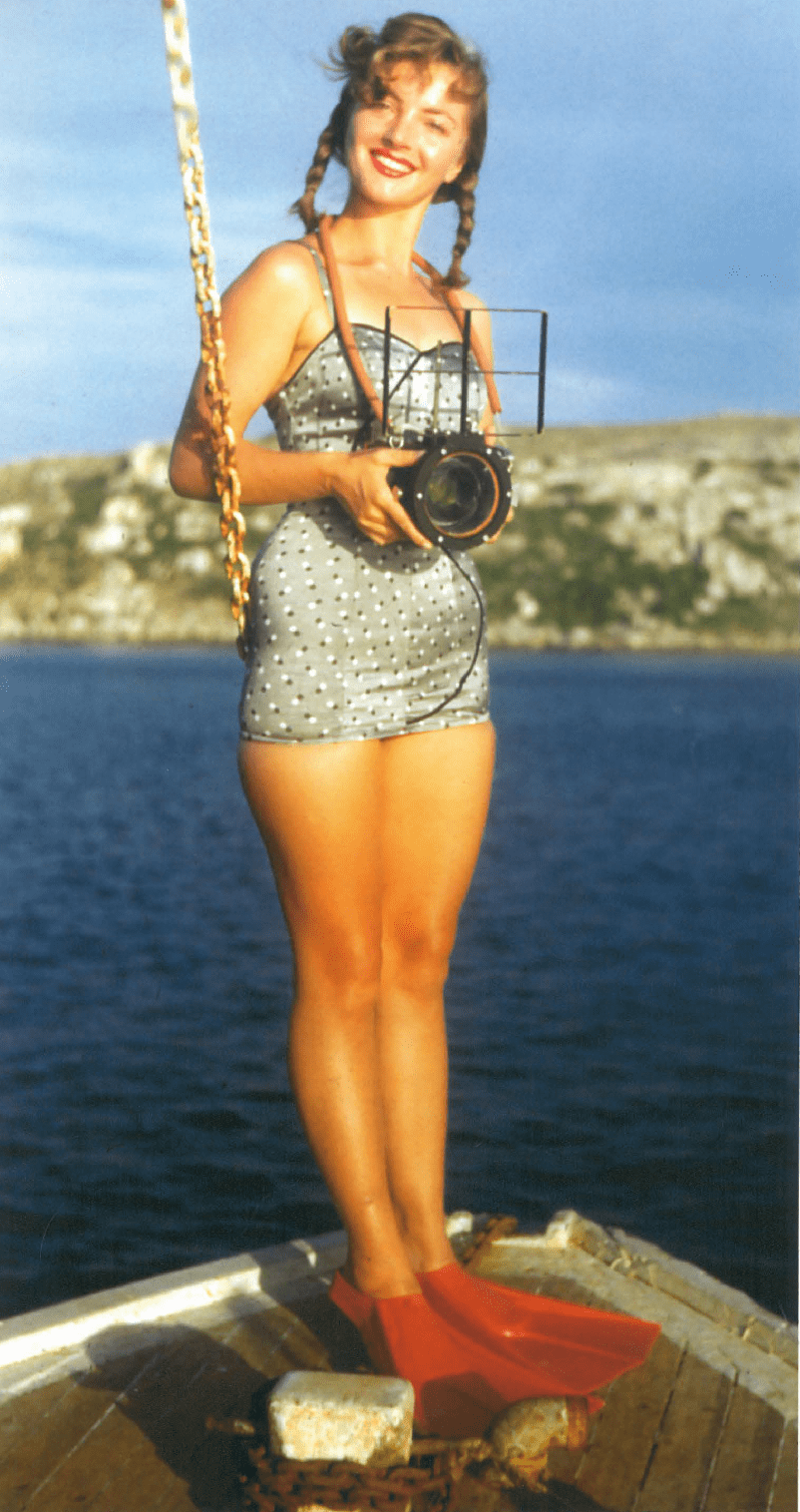

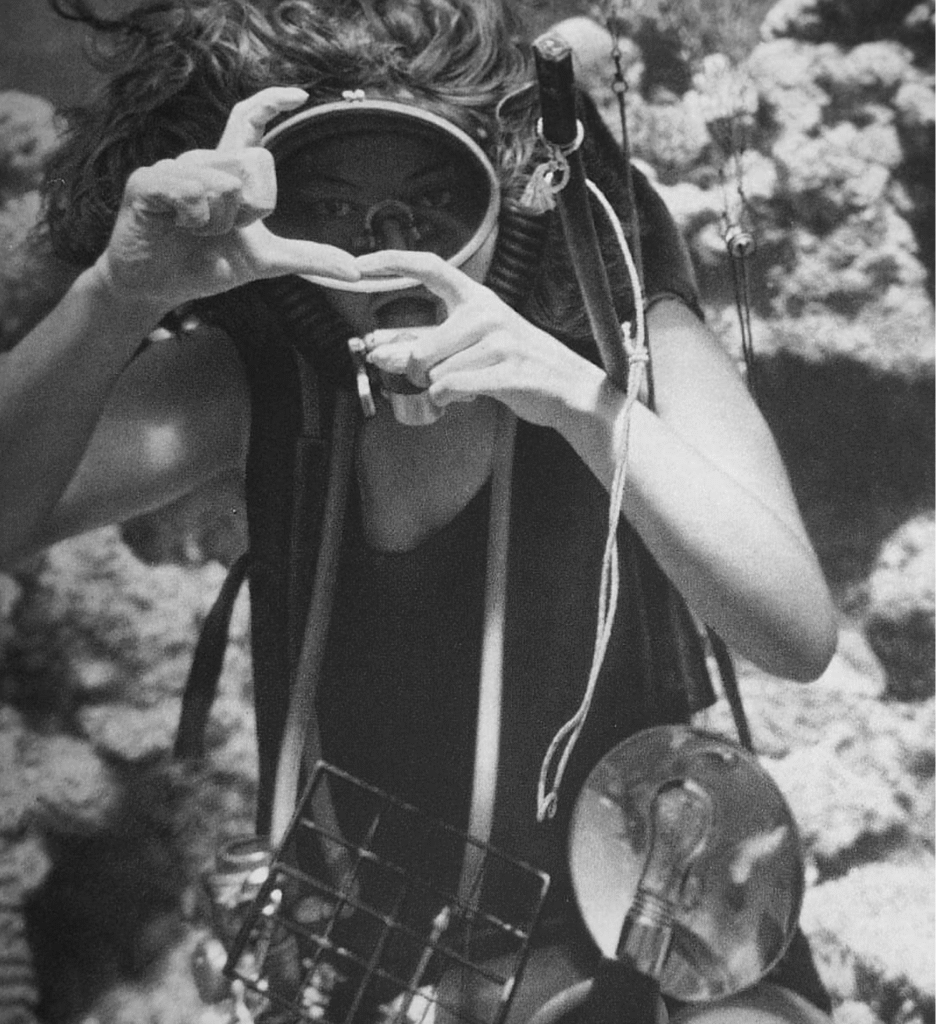

Feature image: Lotte Hass poses with her underwater camera housing. (Source: Hans Hass Institute)

One summer, there was a little girl who couldn’t go to the sea. She had to stay in the city, surrounded by grey buildings and sizzling sidewalks, while her friends left for faraway beaches.

So, every afternoon, she would retreat to her room, open the window to catch a breeze, close her eyes—and imagine. She imagined herself on a salt-scented island, where days drifted by between waves and rocks, halfway between land and ocean.

She saw tiny crabs chasing each other, sea anemones swaying with the currents, and little snails as slow as dreams.With an imaginary mask on her face, she sat on the seabed of her carpet and held her breath. She pretended to be Ariel, the little mermaid—talking to fish, listening to the stories whispered by seashells.

One day, rummaging through a bookshelf at home, she found an old book with a blue cover and a photo of a man in a boat wearing a red beanie. It was Jacques Cousteau, a French naval officer and ocean explorer who co-invented the first underwater breathing apparatus (now commonly called scuba). And inside those pages were underwater worlds full of mystery: sharks, shipwrecks, whales, coral reefs and men exploring the deep. She read it all in one sitting. She admired him. But over time, a question grew inside her:

“And the women? Where are mermaids in these stories?”

One day she asked her mother. Her mom smiled, sat next to her on the bed, and began to speak. She told her that real mermaids had always existed—but their stories were often hidden, silent, like shells resting on the ocean floor. Then she began to tell her about one in particular.

It didn’t begin by the sea, but high in the mountains of a country called Austria. There lived a girl named Lotte, who dreamed of a life filled with adventures, travels, and underwater discoveries. Back then, diving was “a man’s world”. People said the ocean was too dangerous for a girl. But Lotte didn’t believe that. She wanted to be a real mermaid.

And she became one.

Just after finishing school, at age 18, Lotte began working as a secretary for one of the most famous underwater explorers in the world: Hans Hass. But her job wasn’t what she had imagined—her days were full of paperwork, phone calls, and calendars to organise. No diving. No fins. No fish.

And yet, every time Hans told stories about distant seas and coral reefs, Lotte listened with eyes full of wonder. In her free time, she started learning. Quietly. Secretly. No one thought a woman could live such extraordinary adventures. Scuba tanks were as heavy as anchors. Underwater cameras looked like iron suitcases.

But nothing could stop Lotte. She wanted to learn everything—how to breathe underwater, how to use a camera in the deep, how to swim among corals without disturbing them. She wanted to be part of Hans’ team. She wanted to become one of them.

When Hans found out, he tried to change her mind in every way. He told her diving was for men, too hard, too risky. But Lotte didn’t give up. The more they said, “You can’t”, the more she whispered, “Yes, I can.”

And then an unexpected opportunity arrived. Hans was planning a new expedition to the Red Sea. He wanted to film sharks and coral reefs and show their beauty to the world. But to do it, he needed funding. He went to a film studio for help. The producers listened, and then said: “The sea is beautiful but we need something special. A story. A character. Maybe a woman?”

So, a little by chance and a little by necessity, Hans agreed: Lotte would join the expedition.

The heat was unbearable. The work was exhausting. The other crew members were skeptical. But Lotte stayed strong. She had something to prove. And so, she became the first woman to dive in the Red Sea.

At the time, that sea was still almost completely unexplored by scientists, far from tourism, full of wonders. The fish, rays, and coral they encountered had probably never seen a human being with an oxygen tank before! Day by day, fin by fin, Lotte picked up the camera. She learned how to use it better and better. Every photograph was a little piece of ocean she brought back to the surface—to share with others, especially those who, like her, had grown up far from the sea.

After the expedition, Hans and Lotte—now in love—got married. Their documentary won awards and brought the underwater world into homes around the world. But Lotte didn’t stop diving. She kept exploring, filming, and telling the stories of the sea. Her love for the ocean never faded. She received many honours. A tiny reef fish was even named after her: Lotilia graciliosa.

She also became the first European woman inducted into the Women Divers Hall of Fame, a kind of club for real-life ocean heroines—like Sylvia Earle and many others—women who have done amazing things underwater: protecting sharks, exploring underwater caves, teaching others how to dive safely. These women are celebrated for their courage, their curiosity, and their dedication to protecting the ocean.

And so, the little girl who spent her summer at home discovered that real mermaids do exist. They don’t have tails—but they wear fins, carry tanks, and hold cameras. They are women like Lotte Hass, who opened the way when no one thought it was possible. Women who showed that you don’t have to be born by the sea to love it deeply. That even a “no” can turn into a dive toward new possibilities. You just have to believe.

And who knows? Maybe one day, between the rocks of an island or in the heart of a coral reef, you’ll discover that the colorful, silent world beneath the waves belongs to you, too.

Further Reading

Cardone, B. 1996. Women pioneers in diving. Historical Diver 9: 20–25.

Hass, L. 1972. Girl on the Ocean Floor. London: George G. Harrap & Co.