HUNTING IS BANNED BY LAW, YET PERSISTS IN NORTHEAST INDIA. ANIRBAN DATTA-ROY PROVIDES A CLOSER LOOK AT THE PATTERNS OF HUNTING, WITH DETAILS OF NUMBERS, SPECIES AND REASONS

“The ban on hunting doesn’t mean anything. We will stop for a few days and then everything will be the same again,” said a hunter in a remote village in the mountains of Northeast India. Although the ban he was referring to was an official notification in some districts only, it appeared symptomatic of the blundering approach to controlling hunting in Northeast India that has existed for long.”

Hunting in tropical forests is increasingly being recognised as one of the primary threats to biodiversity conservation. Considerable research has gone into illustrating the ecological effects of unsustainable hunting and the consequent changes in community composition of key faunal species. This can eventually result in ‘ecological cascade effects’, where the loss of top predators due to hunting leads to secondary extinctions of prey species. The resultant effects do not stay restricted to animals in the forests. Changes brought about by unsustainable rates of extraction (bordering on causing local extinctions) would mean a loss of ecosystem services for humans too. It would also mean a loss of valuable natural resources for forest dwelling people.

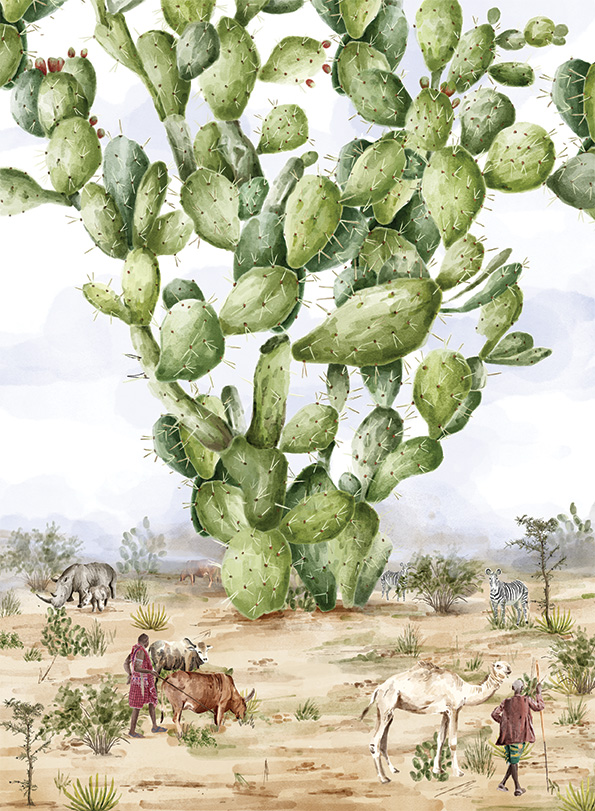

Northeast India, part of the Eastern Himalayas, is an area of exceptional faunal and floral richness and is designated as a global biodiversity hotspot. This area lies adjacent to Southeast Asia and bears close similarities to it in tradition, ethnicity and culture.

Hunting plays a major role in the lives of people here and wild animals are regularly used for food, rituals and medicine. Although prohibited through legislation in the form of the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972, hunting is common place in the Northeast. The reasons behind its persistence are poorly understood, but as an activity that has close linkages with the cultural and socio-economic life of the people of this region, it requires a deeper understanding of the causal factors.

Hunting plays a major role in the lives of people here and wild animals are regularly used for food, rituals and medicine. Although prohibited through legislation in the form of the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972, hunting is common place in the Northeast. The reasons behind its persistence are poorly understood, but as an activity that has close linkages with the cultural and socio-economic life of the people of this region, it requires a deeper understanding of the causal factors.

I conducted an exploratory study on hunting in the Northeast Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh. Refraining from adopting a purely ecological approach, I instead addressed cultural and institutional factors that affect the persistence of hunting in Northeast India. The survey proved invaluable in laying the groundwork for a better-informed long-term study. The study was affected to a great extent by the official notification issued to villages banning all forms of hunting activities at the outset of the survey. Hunters in most places were apprehensive of speaking about their ‘banned’ activities and initially refused to cooperate.

The survey attempted to uncover hunting practices and the motivations behind village-level hunting in Arunachal Pradesh. This was done with four tribes—Monpa, Sherdukpen, Apatani and Adi. The Monpa and Sherdukpen belong to the Mahayana Buddhist sect and provided a contrast to the Apatani and Adi tribes who are animistic in their beliefs (Donyi-Polo religion). To allay fears stemming from the ban, I desisted from taking pictures or recording names of those who seemed particularly wary of speaking about hunting practices. This became especially necessary due to the timing of the government notification banning all forms of hunting two weeks before my arrival for the survey.

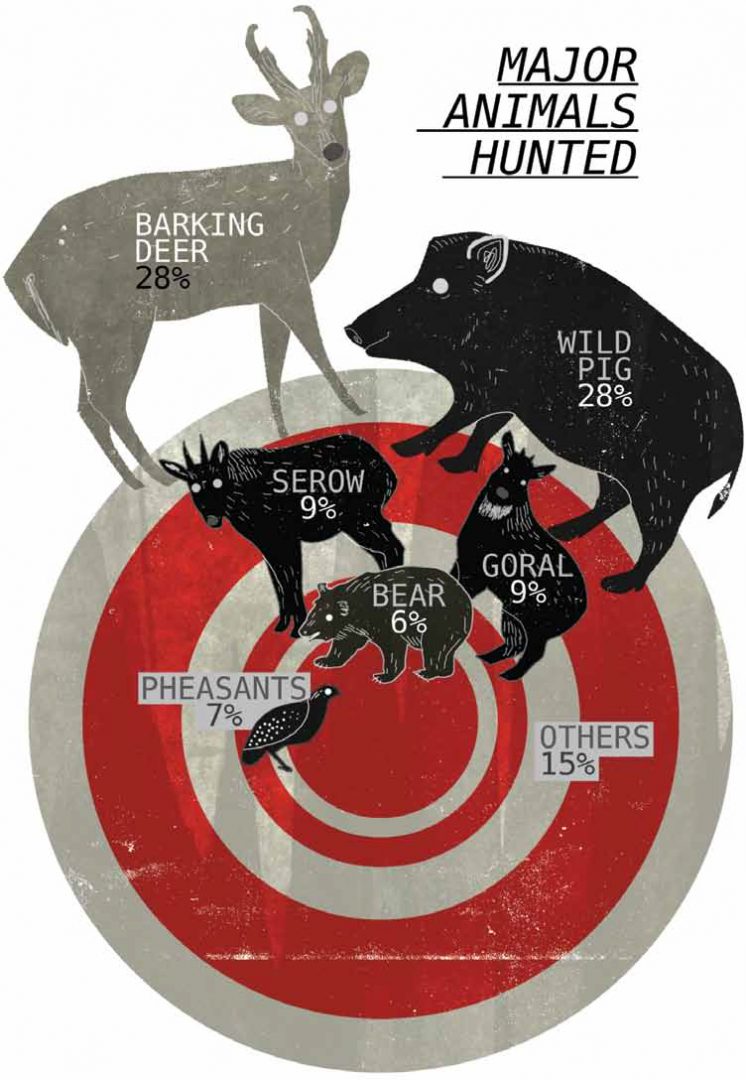

The study focused on areas where hunting occurred almost entirely in community-managed forests. A range of mammals was reported from these community forests with a total of 39 species being identified by hunters across all field sites. Among them, 14 were common to all areas. Among the animals hunted, the barking deer and wild pig are the two species that are most commonly hunted. The presence of endangered and rare animals such as the Asiatic wild dog, the Asiatic black bear and the Malayan porcupine indicates that there still exists a great deal of wildlife in the human-use areas around the villages. Much of this is possible because of the presence of a matrix of community forests and jhum (shifting cultivation) fallows that support many faunal species. In the context of the current debate over ‘inviolate areas’, this is an important reminder of the faunal wealth that still exists outside the protected area network. It also serves to highlight the effectiveness of traditional institutions to manage forest commons in ways that further biodiversity conservation.

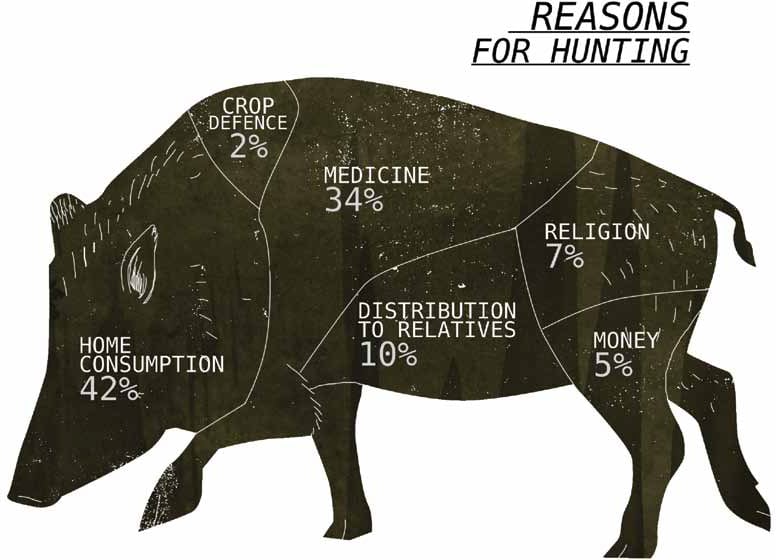

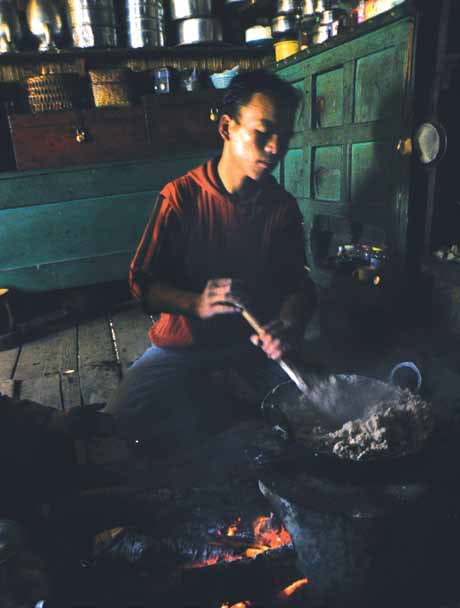

The primary reasons for hunting are said to be domestic use of wild animals for meat and medicinal purposes. It is difficult to distinguish very clearly between these two reasons as sometimes the meat is consumed with the belief that it can cure certain ailments, while at other times there may be specific body parts (like bear gall bladder) that are thought to have medicinal properties. This was consistent across all tribes. Hunting for meat is important to tribal people as the price of domestic meat is extremely high, when it is available for purchase. Most villagers rear domestic animals such as chickens, pigs and mithun, which are seen as a resource that is kept for the future. They are sacrificed on special occasions or used as a currency for fines and other exchanges, and are hardly ever reared for regular consumption. Wild meat, on the other hand, is seen as a ‘free’ resource that is there for the taking.

The primary reasons for hunting are said to be domestic use of wild animals for meat and medicinal purposes. It is difficult to distinguish very clearly between these two reasons as sometimes the meat is consumed with the belief that it can cure certain ailments, while at other times there may be specific body parts (like bear gall bladder) that are thought to have medicinal properties. This was consistent across all tribes. Hunting for meat is important to tribal people as the price of domestic meat is extremely high, when it is available for purchase. Most villagers rear domestic animals such as chickens, pigs and mithun, which are seen as a resource that is kept for the future. They are sacrificed on special occasions or used as a currency for fines and other exchanges, and are hardly ever reared for regular consumption. Wild meat, on the other hand, is seen as a ‘free’ resource that is there for the taking.

Commercial hunting was reported by very few respondents, and hunting for crop defence was also low. It is likely that some of the respondents may not have reported accurately on commercial hunting for fear of official reprisals in view of the newly introduced ‘ban’. However, in later discussions it was revealed that products such as bear gall bladder, musk deer pods and takin skulls have a ready market across the border, while the sale of wild meat within the village is not uncommon.

Hunting during religious festivals and hunting to provide gifts were the other reasons provided. Community hunts that are organised during certain religious festivals are common across most tribes and in some cases a specific species (such as sambar, barking deer or orange-bellied Himalayan squirrel) is hunted. This form of hunting occurs infrequently, about four to five times a year, and the hunts are stopped as soon as the desired animal is killed.

Almost half of the respondents said that they preferred wild meat over domestic meat while only a quarter of the interviewed hunters said that they had no preference. The reasons for the preference of wild meat ranged from taste and tradition to more practical considerations such as the ability to preserve wild meat for longer periods. The source for this wild meat is primarily through hunting by individuals rather than buying. Buying of meat for consumption too was restricted within the village and no respondent reported buying meat from outside the village.

Hunters also reported that whenever a hunt was successful they would share the meat with their relatives and fellow hunters. In addition to being an effective way of strengthening community bonds between people, this is also a sustainable way of utilising resources as this ensures that the greatest number of people benefit from a single kill. The frequency of wild meat consumption is limited by the number of successful hunts that a hunter may have, as the meat that he receives from his relatives or fellow hunters is hardly enough for more than one meal. The frequency of hunting trips is limited in turn by other factors. Winter is considered the best season for hunting due to favourable climate and few farming responsibilities in the jhum fields. Farming is critical for food security and cannot be deserted. It is only towards October, after the harvest, that the villagers have the time to indulge in hunting. Most of the respondents therefore identified winter as the best time for hunting. Winter provides relief from leeches and mosquitoes, while being conducive for night hunting as the hunters can then walk without the fear of snakes. This is also the time when group hunts for high altitude fauna, such as the takin, take place. The seasonal patterns in hunting across different tribes appear to be a reflection of their livelihood practices to some extent. The Monpas live in high altitude areas where jhum cultivation cannot be practised, instead relying on terrace cultivation. The Sherdukpen and Apatani live in valleys and most of their cultivation is of a permanent nature that is irrigated by rivers and streams. The Adi, on the other hand, practice shifting cultivation (jhum) and are entirely dependent on the monsoons. The practice of jhum cultivation is much more labour intensive as it involves clearing, burning, sowing and harvesting the land across a large part of the year. There is hardly any time for hunting except with traps (which require less time investment) during any other time of the year other than the winter months.

Hunters also reported that whenever a hunt was successful they would share the meat with their relatives and fellow hunters. In addition to being an effective way of strengthening community bonds between people, this is also a sustainable way of utilising resources as this ensures that the greatest number of people benefit from a single kill. The frequency of wild meat consumption is limited by the number of successful hunts that a hunter may have, as the meat that he receives from his relatives or fellow hunters is hardly enough for more than one meal. The frequency of hunting trips is limited in turn by other factors. Winter is considered the best season for hunting due to favourable climate and few farming responsibilities in the jhum fields. Farming is critical for food security and cannot be deserted. It is only towards October, after the harvest, that the villagers have the time to indulge in hunting. Most of the respondents therefore identified winter as the best time for hunting. Winter provides relief from leeches and mosquitoes, while being conducive for night hunting as the hunters can then walk without the fear of snakes. This is also the time when group hunts for high altitude fauna, such as the takin, take place. The seasonal patterns in hunting across different tribes appear to be a reflection of their livelihood practices to some extent. The Monpas live in high altitude areas where jhum cultivation cannot be practised, instead relying on terrace cultivation. The Sherdukpen and Apatani live in valleys and most of their cultivation is of a permanent nature that is irrigated by rivers and streams. The Adi, on the other hand, practice shifting cultivation (jhum) and are entirely dependent on the monsoons. The practice of jhum cultivation is much more labour intensive as it involves clearing, burning, sowing and harvesting the land across a large part of the year. There is hardly any time for hunting except with traps (which require less time investment) during any other time of the year other than the winter months.

During the hunting season, most hunts do not last more than a day. This is typical of hunts that occur around the village. Most hunters prefer to hunt in small groups of two to three individuals except for community hunts organised during special festivals. Even the group hunts for takin that last for three to four weeks do not necessarily mean that the hunters hunt together, or that they hunt for the entire duration. They stay together in a common shelter, but mostly hunt on their own. These hunts typically last for barely two to three days while the rest of the time is spent in travelling. The distance that a hunter has to travel for a hunt varied across the different field sites. However, excluding long-distance group hunts, hunters rarely ventured more than 6‐7 km away from their village. The variability was primarily due to the distance of forest or other appropriate hunting areas from the village and the difficulty of the terrain.

During the hunting season, most hunts do not last more than a day. This is typical of hunts that occur around the village. Most hunters prefer to hunt in small groups of two to three individuals except for community hunts organised during special festivals. Even the group hunts for takin that last for three to four weeks do not necessarily mean that the hunters hunt together, or that they hunt for the entire duration. They stay together in a common shelter, but mostly hunt on their own. These hunts typically last for barely two to three days while the rest of the time is spent in travelling. The distance that a hunter has to travel for a hunt varied across the different field sites. However, excluding long-distance group hunts, hunters rarely ventured more than 6‐7 km away from their village. The variability was primarily due to the distance of forest or other appropriate hunting areas from the village and the difficulty of the terrain.

Hunting is almost entirely reliant on modern technology today. Traditional forms of hunting with bows and spears are virtually non-existent and except for one individual, all respondents said that they hunt with guns (in addition to traps and snares). The ownership of guns too provides a great advantage to the hunters as otherwise they are obliged to share a large portion of their kill with the person from whom they may have borrowed the gun. The use of new materials is evident in traps and snares too where metal wires are used instead of the traditional snares made of hide or yak-tail hair. A very large proportion of the hunters who were interviewed had their own guns. In areas like Shergaon in West Kameng, the passage of a major highway has taken gun ownership to surprisingly high levels (there are reportedly close to 150 guns for 130 families)!

An important finding of the study is that hunting, like most activities in the village, is governed by specific rules and regulations. These rules may be characteristic of clan, tribe, religion or might be unique to a particular village. The Buddhist tribes are seen to be more influenced by religious beliefs and the teachings of the Dalai Lama, who has, in the past, personally appealed to them to stop hunting. The Adi hunters stated that they are governed by the community rules established by the village with regard to hunting and other forms of natural resource extraction. Hunting territories of villages are clearly delineated and failure to follow the rules invites heavy fines. At the same time, the Sherdukpen village of Shergaon decided to ban all non-Sherdukpen people from hunting within their area as they felt that outsiders were hunting indiscriminately. This demonstrates the power that traditional institutions still wield, especially in northeast India. If this can be harnessed appropriately, such local institutions can be effective partners to the conventional protected area model of biodiversity conservation. A recent study by Lauren Persha and colleagues (journal Biological Conservation) supports such an approach, suggesting that although strict protected areas are effective tools for biodiversity conservation, ‘a singular focus on them risks ignoring other resource governance approaches that can fruitfully complement existing conservation regimes.’

An important finding of the study is that hunting, like most activities in the village, is governed by specific rules and regulations. These rules may be characteristic of clan, tribe, religion or might be unique to a particular village. The Buddhist tribes are seen to be more influenced by religious beliefs and the teachings of the Dalai Lama, who has, in the past, personally appealed to them to stop hunting. The Adi hunters stated that they are governed by the community rules established by the village with regard to hunting and other forms of natural resource extraction. Hunting territories of villages are clearly delineated and failure to follow the rules invites heavy fines. At the same time, the Sherdukpen village of Shergaon decided to ban all non-Sherdukpen people from hunting within their area as they felt that outsiders were hunting indiscriminately. This demonstrates the power that traditional institutions still wield, especially in northeast India. If this can be harnessed appropriately, such local institutions can be effective partners to the conventional protected area model of biodiversity conservation. A recent study by Lauren Persha and colleagues (journal Biological Conservation) supports such an approach, suggesting that although strict protected areas are effective tools for biodiversity conservation, ‘a singular focus on them risks ignoring other resource governance approaches that can fruitfully complement existing conservation regimes.’

Various taboos are also attached to killing of different animals and are found among all tribes. This is most prominently observed in the reluctance of the Buddhist tribes to kill primates. Various reasons were put forward by hunters in the case of primates, some of which were related to their similarity in physical appearance to humans, bad taste, as well as incidents when killing of monkeys resulted in disease outbreaks or death for villagers. The reasons for sparing certain animals are hard to locate and may be due to behavioural patterns and morphological characteristics of the species, the belief that they are toxic, cultural perceptions of the animal being part of creation myths or even representing religious symbols. These are, however, important inbuilt control measures that serve to regulate the intensity and magnitude of hunting.

The government notification on banning hunting hardly served any purpose as the implementation of such bans are logistically impossible for the concerned departments in such remote areas. Hunters stated that this ban would not stop them from hunting and they would continue to do so, as this is what they have always done. The ban disregarded the fact that hunting has deep historical, social and cultural connections among the people of the area. Such token bans in fact run the risk of criminalising a social practice and merely moving it underground, where it will continue to exist, free from local institutions as well as the government.

Future policies aimed at hunting need to break free from these conventional approaches that have proven to be ineffective in the past. Traditional resource management institutions in the village wield a great deal of power in the formulation and enforcement of rules in tribal societies. Without adequate involvement and participation of these institutions, it is unlikely that any policy on hunting can be implemented effectively.

Future policies aimed at hunting need to break free from these conventional approaches that have proven to be ineffective in the past. Traditional resource management institutions in the village wield a great deal of power in the formulation and enforcement of rules in tribal societies. Without adequate involvement and participation of these institutions, it is unlikely that any policy on hunting can be implemented effectively.

The biggest threat currently is the gradual commercialisation of hunting in Arunachal Pradesh, with growing demands for wild meat from urban centres, and for skins and other body parts from across the border. There are hardly any checks on the sale of wild meat in urban markets and token bans appear to serve no purpose. This threatens to cause dramatic changes that may affect wildlife populations as well as the people who depend on them. In view of these impending changes, it becomes even more imperative to equip the local institutions to tackle these problems on their own. An effective partnership could dispel much of the distrust that exists between both sides and provide a more pragmatic approach to controlling hunting in Northeast India.

Anirban Datta Roy is a PhD student at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment, India. anirban@atree.org

Illustrations: Prabha Mallya

Photographs: Anirban Datta-Roy