The 17th and 18th century witnessed intense competition among the British, Dutch and French East India companies to monopolise trade, commerce and knowledge in South and Southeast Asia. While key trade routes of the region were usurped as a result of defining battles, scholars from these European nations also raced to study the geology, ethnology, linguistics and most notably the flora and fauna of these exotic lands, often piggybacking on the armies of their countries. During this period of British dominance, one man, Thomas Horsfield, stands out as one of only a few Americans from that newly born nation to study and document the natural history of the South and Southeast Asian region.

BEGINNINGS

Born on the 12th of May 1773 in Bethlehem, a small town in eastern Pennsylvania in the then British North America, Thomas Horsfield belonged to the Moravian sect of Christianity. From an early age he showed interest in all branches of biology, especially botany. While working towards a degree in medicine from the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, he studied the toxic effects of the poison ivy (Rhus toxicodendron) for his thesis. It was this interest in plants, particularly those with medicinal properties that led to his natural history career.

EDEN OF THE EAST

In 1799, a year after graduating in medicine, Horsfield took up the Surgeon’s post on the American merchant ship, China, bound for Asia. During its voyage from the United States to Southeast Asia, the merchantman briefly docked in Batavia, better known today as Jakarta, capital of Indonesia. The natural beauty of the island and the rich variety of medicinal plants that the natives used enthralled Horsfield; he returned to the archipelago in 1801 as a Surgeon for the Dutch East India Army, a position that gave him great freedom to explore the island. For the next 18 years, Horsfield studied the flora, fauna and geology of Java, working initially with limited funds from the Batavian Society of Arts and Science, a group of educated Dutch settlers on the island. Much of his specimens, during these early years in Java, were lost because of poor equipment and collection practices.

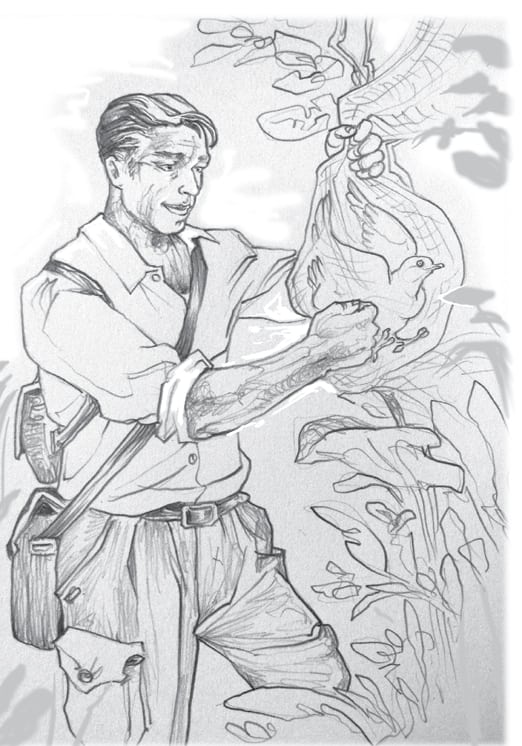

Fortunately, in 1811, when the British East India Company took over the island Horsfield met Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, the new Lieutenant Governor of the island, better remembered today as the founder of Singapore. It was an odd friendship between a man from a deeply religious sect formed on the tenets of love and non-violence, and Raffles a man believed to be both visionary and ruthless in the expansion of the British East India Company. What the two had in common though was their interest in natural history; the founder of the Zoological Society of London and the London Zoo, Raffles was an enthusiastic naturalist himself, and encouraged Horsfield’s work on the natural history of the East Indies. Under his patronage, Horsfield officially joined the British Company as a surgeon. For the next eight years, he travelled extensively on the island of Java and later Sumatra observing various taxa and making detailed notes on their behaviour and natural history. He also collected valuable specimens of flora that he donated to the Royal Botanical Gardens in Kew and fauna that he sent to the India Museum (founded 1801) of the East India Company in Leadenhall Street, London.

However, he was forced to move to a temperate surrounding after his health deteriorated. He continued to be under Raffles’ patronage and in 1819, was appointed the curator of the India Museum, a position he kept until his death in 1859. During his time in London, Horsfield synthesised his work in Southeast Asia, into his best known book, Zoological Researches in Java and the neighbouring islands.

Published in eight parts from 1821-1824, the book was a synthesis of knowledge of fauna of Java, and provided notes on the taxonomy, morphological characteristics and some behavioural observations on primates, bats and birds by various naturalists including Raffles. While several of the species mentioned in the book have since undergone substantial taxonomic revision, the book remains relevant for its physical and behavioural descriptions of species that are restricted to few unexplored islands in Southeast Asia.

INDIAN MAMMOLOGY

Although he never visited India, Horsfield was responsible for describing several mammals and plants found in the region. A huge number of floral and faunal specimens from India started to flood the India Museum collection. Horsfield painstakingly examined, identified and catalogued these specimens. This resulted in the description of six new mammalian species from India and neighboring regions—the Intermediate horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus affinis) and the Intermediate round-leaf bat (Hipposideros larvatus) in 1823, Hardwicke’s forest bat (Kerivoula hardwickii) in 1824, the golden cat (Pardofelis temminckii) in 1827, the Common yellowbellied bat (Scotophilus heathii) in 1831 and the Himalayan striped squirrel (Tamiops mcclellandii) in 1840. In 1851, he published what could be his most extensive work on the Indian subcontinent—The Catalogue of the Mammalia in the Museum of the East India Company. In this book he described all the mammals from this region in great detail, including their taxonomy, and added five mammal species new to science including the Indian endemic bare-bellied hedgehog (Paraechinus nudiventris) and the elusive Nilgiri marten (Martes gwatkinsii).

LATE RECOGNITION

Despite his many accomplishments recognition was hard to come by in English society, where one’s lineage mattered. It was finally perhaps his friendship with Raffles that led to his being elected the First Assistant Secretary of the Zoological Society of London at its formation in 1826 and subsequently a fellow of the Royal Society in 1828. However, several naturalists from the Indian subcontinent such as George Gray and John Gould paid tribute to Horsfield by naming new species of animals they discovered, such as the Javanese flying squirrel (Iomys horsfieldii) and the Horsfield’s fruit bat (Cynopterus horsfieldi) after him. On the 24th of July 1859, Horsfield passed away in his English home in Camden Town, London, at the age of 86. After his death, all his personal papers were destroyed according to his prior instructions.

Owing to this we have little information about his personal life. Why he undertook such a course of action is now a matter of speculation—perhaps he wished to conceal something or as some historians speculate, in keeping with the Moravian traditions of modesty and privacy, he believed his personal life would be of little interest to others. What we do know however is that he left behind a great legacy in terms of the natural history of India and Southeast Asia.

Suggested reading:

John Bastin. 1978. ‘A Pioneer American Naturalist of Indonesia: Dr Thomas Horsfield’, Indonesia and Malay world newsletter, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

G K Harrington. 1997. ‘Thomas Horsfield: An American Enigma’, the International Institute for Asian Studies Newsletter.