Rivers have served as lifelines throughout human history. Over thousands of years, civilisations have flourished and perished along the banks of different rivers across continents. Few terrestrial life forms can survive or thrive without access to clean freshwater. However, in the Anthropocene, humans continue to act oblivious to all the lessons from our history. Today, we find ourselves in this detrimentally extractive state of existence, where rivers are subjected to continuous contamination, irreversible damage, and steady degeneration.

We share this planet with millions of life forms, all of which deserve a chance to survive, grow, and live a peaceful life. As a result of our anthropocentric view of growth and development cultivated over the centuries, however, we have disturbed the order and balance of nature, exacerbating the loss of biodiversity.

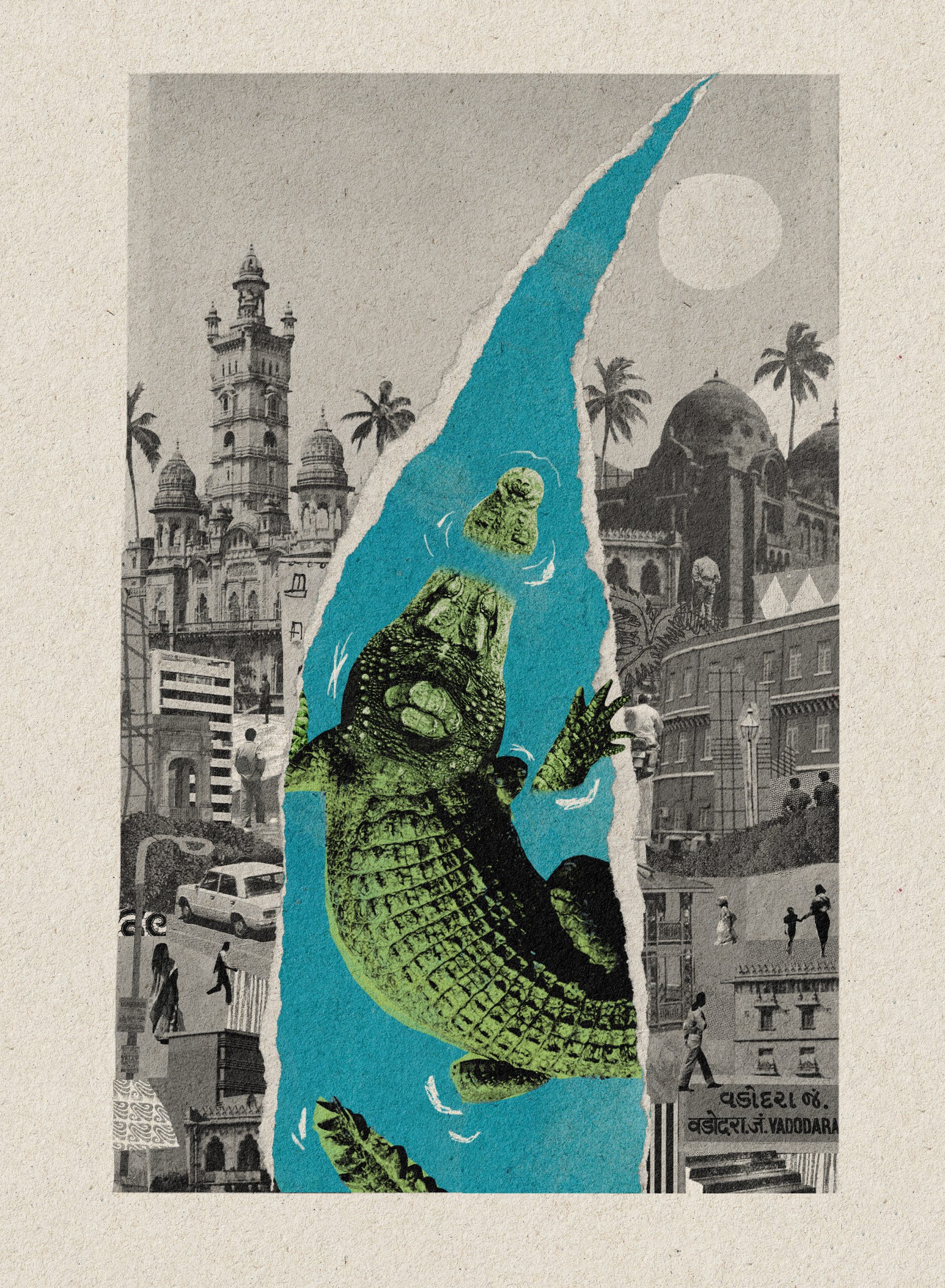

On this note, I present an anecdote about the Vishwamitri River. Vishwamitri is a small non-perennial river, about 200 km in length. Located in the westernmost state of India, Gujarat, this rain-fed river originates in the Pavagadh hills and flows west to meet the Gulf of Khambhat. In between, Vishwamitri flows through a densely populated urban centre, the city of Vadodara. And within this city and its surroundings lie urban pockets which are home to more than 300 marsh crocodiles (Crocodylus palustris) or muggers. As a resident of Vadodara for nearly four decades, I present this emblematic account of the existence between humans and muggers based on first-hand observations and experiences.

Transformation of the Banyan City

Vadodara was once the capital of the princely state of Gaekwads, later anglicised as Baroda during the colonial era. Before the Gaekwads, Vadodara was known as Chandravati under the reign of Chanda of the Dodiya Rajput dynasty. Historically, the city was renamed from time to time, with shifts in power and control. After independence from the British in 1947, it came to be known by its current name: Vadodara or the Banyan City.

With rapid urbanisation and industrialisation, the demographics of Vadodara changed faster than ever. As Vadodara continued to grow as an urban centre, the demand for housing and land grew exceedingly. This demand and the institutionalisation of the real estate industry was subsequently translated into a large-scale deforestation drive. The groves of banyan trees (Ficus bengalensis), which once reflected Vadodara’s identity, were lost. Within a few decades, most of the banyan groves and pockets of wilderness disappeared. Similar to the fate of other contemporary cities, the quest for cosmo politanism and a modern identity resulted in a near-complete erasure of Vadodara’s heritage and unique identity.

Vadodara embraced its new identity as an industrial and student city. Alongside industries followed tech parks and the suburbs. It saw a steady rise in the influx of diverse settlers from near and far. Once a beautiful cultural capital and Gaekwad’s legacy, the city became a bustling metropolis, imitating global trends and chasing development.

Changing ecology

The Vishwamitri River changes as it travels from the rural to the suburban and urban landscapes. The parts of Vishwamitri that cut across the city have murky, black, frothy waters polluted with industrial and medical waste and debris. Along with its appearance, the river’s ecology changes unrecognisably. The calm waters of the river become muddy, erratic and problematic. The depths are artificially manipulated as and where needs arise.

Monsoon, historically romanticised and cherished, has become a nightmare for the citizens, to the extent that the municipal corporation has to survey and repair the entire city at the end of every season. A few inches of rain quickly flood most of the city and almost all the suburbs. The river goes from being the harbinger of life to a dreadful force of nature. The same riverside that defines the architecture and approach to all of the city’s historical monuments now falls in the most overlooked flood zones. Citywide evacuations, rescues, and rehabilitation occur invariably, testing the resilience of Vadodara’s residents.

The data maintained by the local Forest Department shows alarming numbers of wildlife rescues, including snakes and marsh crocodiles, from human settlement areas every year. Additionally, more than a hundred volunteers from over half a dozen civil society organisations provide wildlife rescue services round the clock. According to the official data, over a thousand snakes and six dozen different-sized muggers are rescued annually.

The Banyan City now identifies with an abundance of muggers. As the apex predators of freshwater ecosystems, muggers have adapted to urbanisation, predominantly scavenging and feeding on carcasses. Alongside the disappearance of riverine habitat and scrub forests, the natural habitat of scavengers such as golden jackals (Canis aureus) and white-rumped vultures (Gyps bengalensis) also disappeared from the city. Thus, with scavengers becoming locally extinct, the muggers serve an important function by picking dead matter off the river banks.

Cohabitation, conflict and coexistence

Muggers have been cleaning up the river over the last three decades. As a result, the urban popula tion of muggers has been growing steadily. And with cohabitation has come territorial tension between humans and muggers, each reclaiming their habitats and place in the city. While humans dominate the lands, muggers maintain control over the waters. In Vadodara, this interspecies tug-of-war is now commonplace.

Human-crocodile interactions have increased, resulting in frequent encounters and occasional conflicts. In 2021 and 2022, there were 344 mugger rescues, nine non-fatal mugger attacks on people, 15 dead muggers found where cause of death was unknown, and five muggers killed by vehicular traffic. Sometimes, humans suffer, and other times muggers.

We cannot overlook or dismiss the current reality where the existing harmony between Barodians and muggers is occasionally interrupted, leading to a dilemma and uncertainty. There have been records of muggers attacks where people lost their lives. If not fatal, there are several cases where the victims were left with a permanent disability. There have been instances of people seeking revenge by injuring or killing the crocodiles, or destroying their nests and habitats. Such attitudes and incidents pose a perpetual threat to the delicate coexistence of humans and wildlife in dense urban environments, and remains a challenge for urban wildlife conservation.

Despite these challenges, the term Barodians has come to include both humans and muggers cohabiting in the city. Thus Vadodara, once the Banyan City, may now be better described as the ‘Mugger City’.

Further Reading

Vyas, R. 2014. Roads and Railway: Cause for mortality of Muggers (Crocodylus palustris) Gujarat State, India. Russian Journal of herpetology 21(3): 237–240.

Vyas, R. and C. Stevenson. 2017. Review and analysis of human and Mugger Crocodile conflict in Gujarat, India from 1960 to 2013. Journal of threatened taxa 9(12): 11016–11024.

Vyas, R. and A. Vasava. 2019. Mugger crocodile (Crocodylus palustris) mortality due to roads and railways in Gujarat, India. Herpetological conservation and biology 14(3): 615–626.

Vyas, R., Vasava, A. and V. Mistry. 2020. Mugger crocodile (Crocodylus palustris) interactions with discarded rubbish in Central Gujarat, India. CSG newsletter 39(2): 5–11