“We haven’t used the bathroom for three days,” said the man apologetically in Kannada on the phone. No medical problem prevented his family from using the room. They had a different issue—a king cobra had moved in. They were now desperate to regain use of the room.

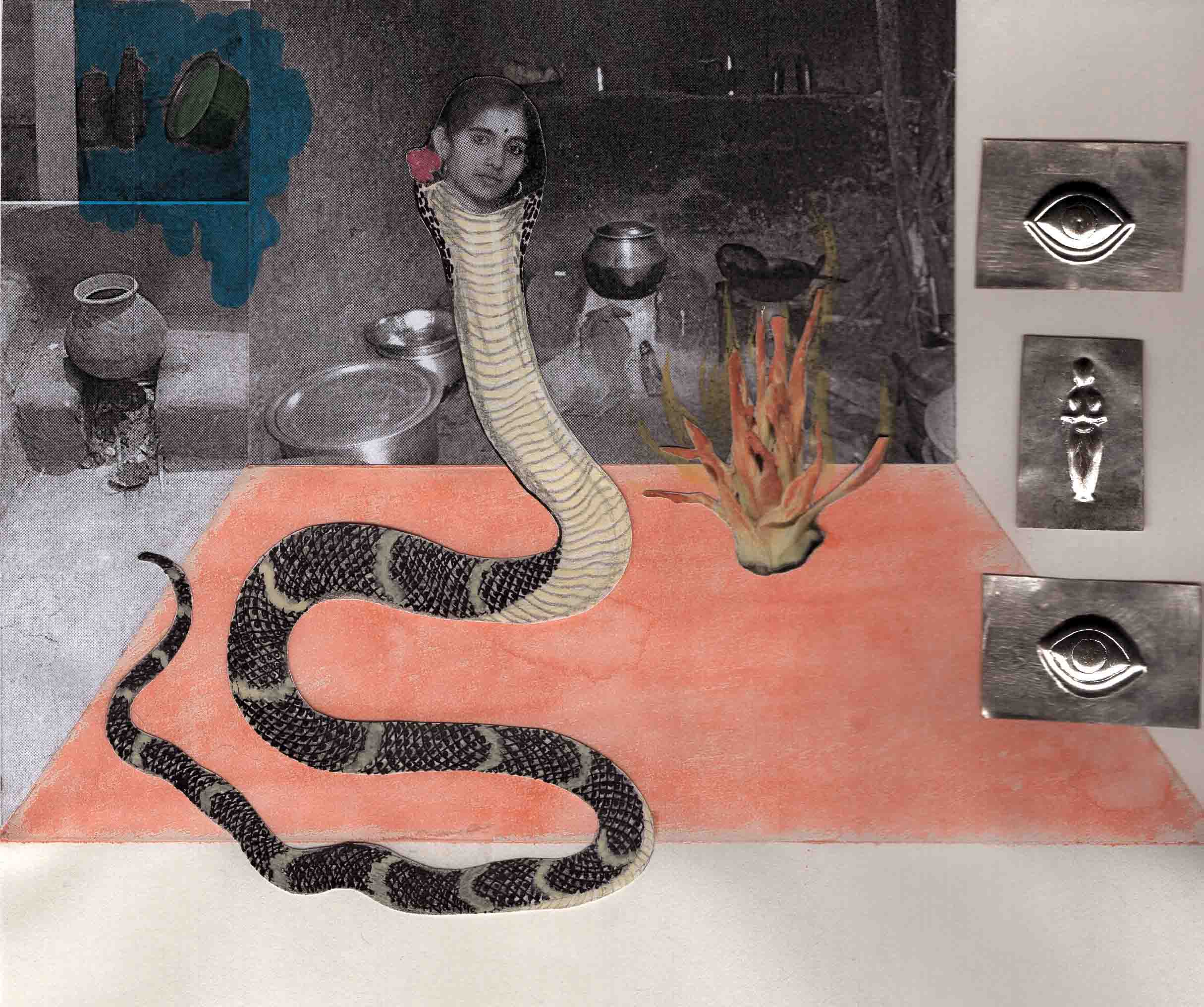

As in any traditional Malnad house, a concrete lip of single brick thickness demarcated the square bathing area in one corner of the room. The family and neighbours crowded the doorway. As the snake catchers’ eyes adjusted to the dim light, they saw the black snake coiled on the red floor. Golden yellow lines encircled its body at regular intervals like nodes on a bamboo culm. A gunny sack lay nearby.

“The cement is chipped there,” the lady of the household in Agumbe explained. “We were worried the snake may hurt itself crawling over the rough edge.” As the catchers debated the plan of action, the family wanted repeated assurances that no harm would befall the king cobra, a revered being.

“If there’s any chance that it will get injured, please don’t catch it,” said the husband. Not only was the cost of performing a puja of repentance prohibitive, but clobbering it to death would be unthinkable. King cobras, in this part of the world, are worshipped as a god.

The family members had left the bathroom door ajar so the king cobra could find its way out on its own. When it showed no signs of taking the hint, neighbours convinced them to call the Agumbe Rainforest Research Station for help. During those three days, the snake could have reached up over the wall, crawled along the rafters, and entered any other room.

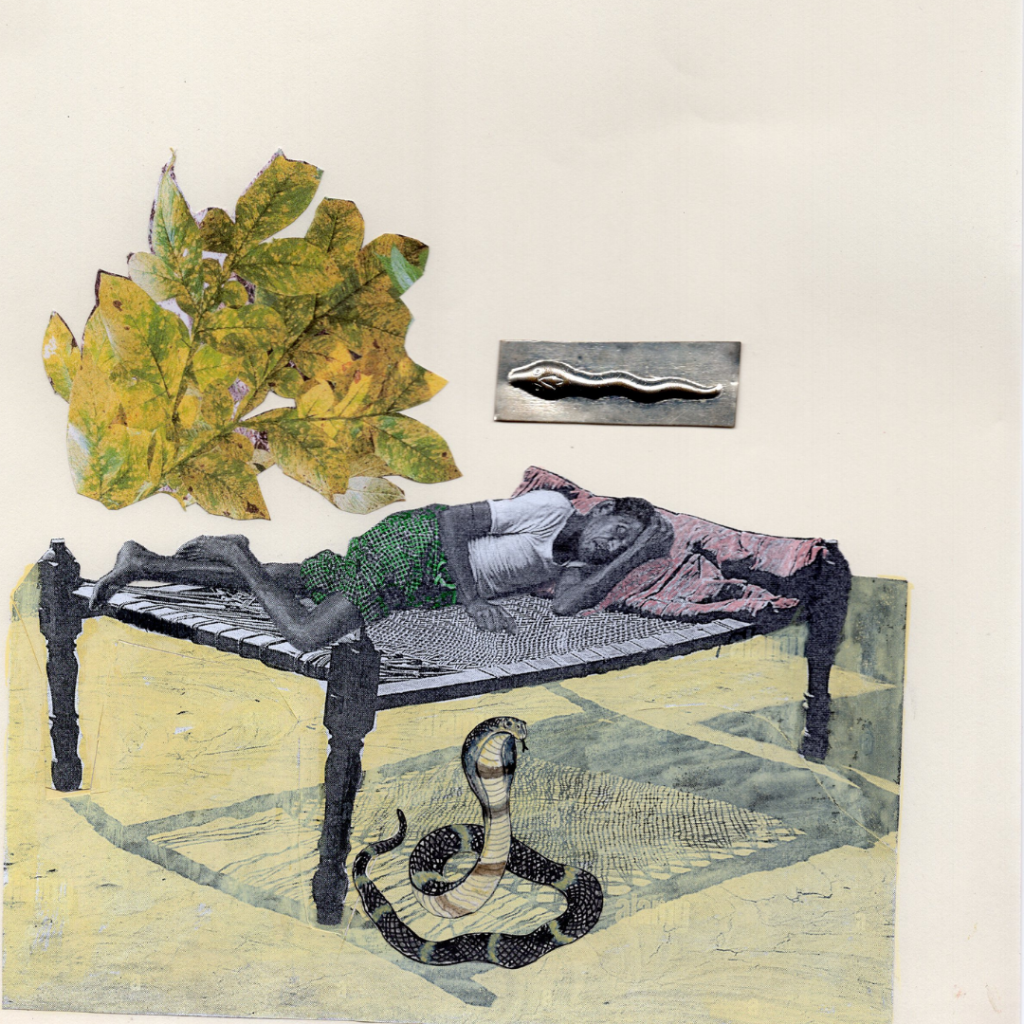

What kind of family stops using the bathroom for days, prevents a wild snake from hurting itself, and sleeps in the same house with it? The creature they fussed over was no piddling little thing. At 10-feet long, it was a member of the world’s largest venomous snake species. King cobras, like the proverbial camel in the Arab’s tent, take full advantage of the benevolent Malnad farmers by holing up in bathrooms, beneath beds, and on roofs. Occasionally, they even attempt to stow away in automobiles.

Not everyone in Agumbe shares the same religious beliefs and they can be hostile to snakes. The majority, however, recognise king cobras for what they are — intelligent giants unwilling to waste their golden venom on inedible morsels like us. King cobras bite so few people, not counting inept rescuers, that one has to dig through the archives to find the last case. The team of snake rescuers at the research station have, over the past decade, made people realise that there’s another reason to leave the snakes alone: they perform a valuable service, readily gobbling up smaller snakes like vipers and cobras that kill thousands of people.

Such an attitude is not common in other parts of Karnataka, or in Indian states such as Andhra Pradesh and Mizoram, and elsewhere in the species’ Asian range, where any king cobra that shows itself to humans is as good as dead. While the relationship between king cobras and the residents of Agumbe is no doubt special, is it possible, or even sensible, for people to share a similar bond with regular cobras which cause mass fatalities?

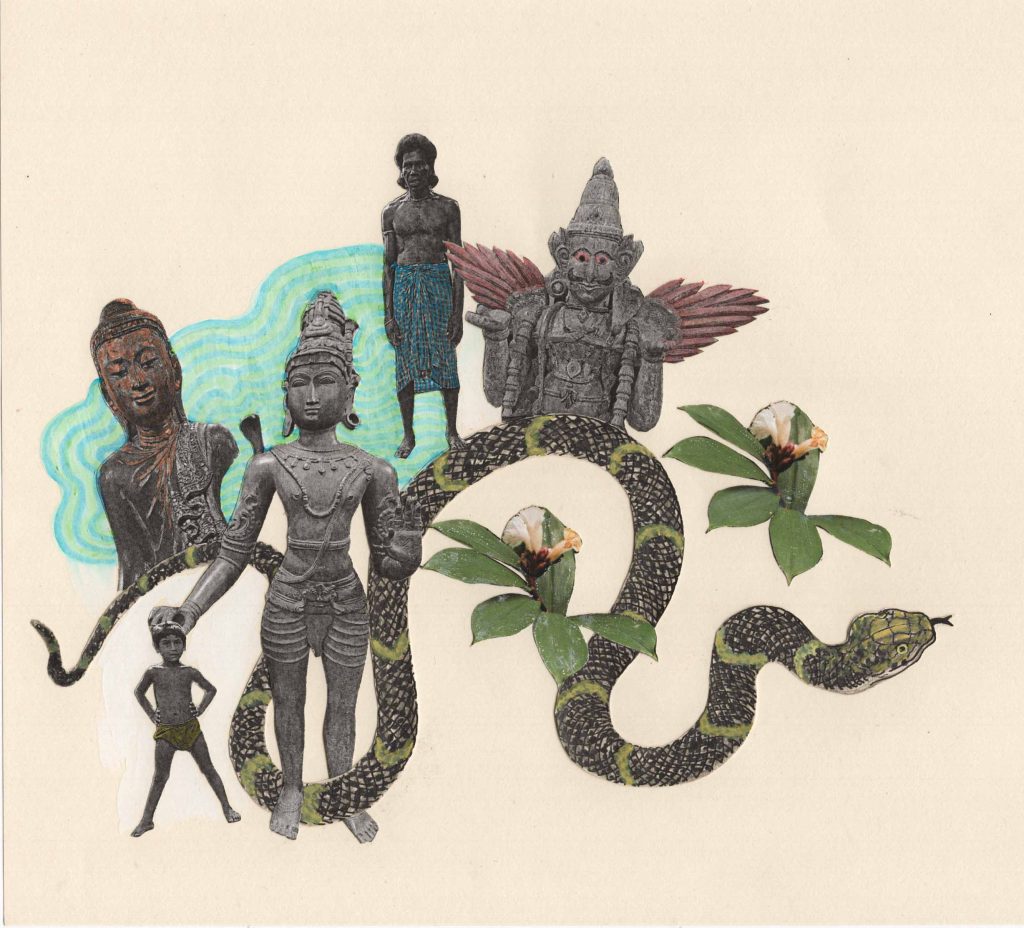

Across the country, Indians worship cobras. Our temple iconography shows these reptiles as the ornaments of Shiva and Ganesha, the bed of Vishnu, and the umbrella of Buddha. In several parts of the country, the devout sanctify termite hills as the abodes of these sacred snakes. Besides being objects of veneration, cobras serve a useful purpose around houses and farms: eating rodents. But their pest control assistance is overshadowed by their ability to kill. It’s no surprise that many people look for quick ways of despatching them from this world.

Basavanna, a poet-saint from 12th-century Karnataka, captured our conflicted feelings towards snakes thus:

When they see a serpent carved in stone, they pour milk on it,

If a real serpent comes, they say, ‘Kill, kill’.

(The Great Integrators: The Saint Singers of India)

At the other end of the country, the residents of Boro Posla, Musharu, and a few other neighbouring villages in Burdwan District, West Bengal, however, have an entirely different outlook. Cobras have every reason to fear humans, and they are mainly creatures of the twilight hour. But here, they go about their business in broad daylight, foraging around houses and courtyards, while the human residents carry on with their own affairs, paying little attention to the reptiles. The unafraid cobras never spread a hood to display the startling eye-like marking.

The reason for these villagers’ apparent suicidal mindset is the presiding goddess Jhankeswari, after whom cobras get their local name, jhanklai. According to folklore, the deity won’t let the snakes harm her devotees and they don’t molest the reptiles. Everyone in the villages abides by this culture of getting along with one of the most dangerous serpents in the world.

Where even Agumbe’s inhabitants draw the line, these villagers are casual about the cobras. In the face of this sangfroid attitude, the snakes take great liberties, slithering through living rooms past children doing their homework, swallowing toads under beds, gobbling chicken eggs in coops, and sleeping among pots and pans in kitchens. The people neither call snake catchers to remove them nor do they drive the serpents out themselves. In fact, only the priest of the Jhankeswari temple is allowed to handle them. As the women cook and wash dishes, they talk to the jhanklai as if to their confidants. If the reptiles are in their way, they request them to move. If the deaf creatures fail to obey, they bang plates or buckets. More than the noise, the ladies’ sudden actions make the serpents move.

Lest this give the impression that these monocled cobras are harmless, in West Bengal state, nearly 43,000 victims died over 13 years from snakebite. Neither the spectacled nor the monocled cobra has the gravitas or the reputation for self-restraint that king cobras have.

The jhanklai do occasionally bite people. One lunged at a woman walking through her courtyard. But it was a ‘dry’ bite, as the snake didn’t inject any venom. In another case, a mouse fleeing a cobra dove under a gunny sack being used as a doormat. A three-year-old boy entered the room at that moment and the hunting snake bit his foot. He was treated in a hospital and bore the scar of tissue damage. Almost all the bites were feeding responses when hungry snakes mistook a human hand or foot for prey.

Despite the inconvenience of these mishaps, the villagers are convinced none will lose their lives to a cobra bite and continue to grant their jhanklai as much of a right to reside in their households as their families.

To the people of Agumbe and the villages of Burdwan who live with king cobras and cobras, the ecological and utilitarian arguments are irrelevant. They live by the foundational beliefs governing their worldview of mutual respect. Even though the king cobra had caused discomfort and the snake catchers caught it with skill, that family prayed for forgiveness from the inconvenienced divinity. It has to be acknowledged that such reverence is selective. In both places, there is no tolerance for other species such as Russell’s vipers.

Basavanna sang about the hypocrisy of the majority, but he neglected to sing paeans to his fellow countrymen who live by their convictions.

An edited version of this articleappeared in THE HINDU SUNDAY MAGAZINE on 18 March 2017.