At the precipice of the contemporary environmental movement is an immediate need for the greater inclusion of strategic visual communication in the form of conservation photography. Conservation photography is simply photography that empowers conservation. It involves the active use of the photographic process and its products, within the parameters of journalistic activity, to achieve concrete conservation outcomes in the context of the bio- cultural landscape.

Conservation photography is not yet widely acknowledged. However, photography has been used as a conservation tool since the early days of landscape photography. William Henry Jackson’s 1871 images of Yellowstone influenced legislators to create the first U.S. National Park to protect wilderness. Today, in a society that depends even more heavily on visual communication platforms to send and receive information, conservation photography can be increasingly employed as a conduit for sharing environmental messages with the public at large. Most significantly, conservation photography practice involves placing images in front of influential people whose decisions can elicit tangible conservation action, such as policy-makers, government officials, funders, and corporations.

The ability of an audience to “read” conservation images is crucial to these processes. Similarly, the creation of conservation imagery requires a photographer who can intentionally construct an authenticate visual representation of an environmental issue or concern. The effectiveness of conservation photography is dependent upon the ability of photographers and viewers to thoughtfully create and interpret visuals- in other words, their ability to be visually literate.

Visual literacy is a burgeoning area of study that involves a critical approach to the creation and interpretation of images. Notable contributor to the field, Cyndi Giorgis, defined visual literacy as the ability to construct meaning from visual images. Anne Bamford, recognized internationally for her research in arts education, emerging literacies and visual communication, described visuals as having the capacity to produce and communicate thoughts and images about reality. This visual vocabulary is a powerful tool that conservation photographers use to express their messages. “For scientists and communicators concerned with the natural environment, visual literacy is of paramount importance. If the images are not comprehensible to a lay audience, the message is lost,” noted Jean Trumbo in a 2007 article on visual literacy and the environment.

Visual literacy involves understanding the language of representation used to create meaning about the world around us through images. In the same way that a sentence can be broken down into parts, an image can be dissected through syntax and semantics. In a visual literacy whitepaper, Bamford described syntax as the building blocks of an image-elements such as perspective and framing, or balance and tone. Semantics, on the other hand, refers to “the way images relate more broadly to issues in the world to gain meaning.” This is addressed in conservation photography by asking such questions as:

- Who commissioned the image (e.g. government/ corporation/NGO)?

- Who is the intended viewer (e.g. general public, scientists, policy-makers, government)?

- What environmental or conservation issue(s) is communicated in the image?

- What environmental components are emphasized/ omitted?

- Is there a juxtaposition of opposing elements?

- Are there opposing conservation attitudes depicted in the image?

- What are the positive/negative connotations of the image?

“Photographs are objects that channel affect in ways that often seem magical.” – Marita Sturken and Lisa Cartwright, 2008

Conservation imagery is adept at conjuring emotions, port- raying the devastating (e.g. an oil-slicked pelican) as well as the stunning (e.g. a verdant rainforest vista). Yet, this emotion is often tied to cultural context.

Roland Barthes used the terms denotative and connotative to describe this concept. Denotative refers to what an image depicts in a literal way, without any inference. Connotative refers to the culturally and emotionally significant meaning of an image-the aspects that resonate with the viewer as described by Marita Sturken and Lisa Cartwright in Practices of Looking. Conservation photography aims to use images as springboards for discussion, and visual literacy skills set the stage for critical thinking. Educator Robert Phillips notes that learning “skills and attitudes for viewing pictures can assist in understanding the form, content and context of visual images, and help them to critically assess the inherent qualities, veracity, and agency of images.”

Adopting a visual literacy approach to viewing conservation images, we can analyze photographs such as the image of the man with turtle. We start by identifying the denotative and connotative aspects of the image, and then dissect its syntax and semantics. To begin, we describe the image denotatively. It depicts a man standing on a beach holding a turtle. Behind him, we see several fish lying on the sand on one side, and a black net on the other. Next, we explore the connotative meaning of the image. What personal experience do we have that influences how we interpret this photograph? Someone with a fishing background, for example, might sympathize with the human subject of this image and admire how proud the man is of his catch. For some, the tropical beach location might be interpreted as exotic. Our personal context shapes the connotations we draw from the image.

“A photograph can’t coerce. It won’t do the moral work for us, but it can start us on the way.” – Susan Sontag, 1973

Syntax, or the arrangement of visual elements, allows us to examine the intent of the photographer and the conscious choices they made while creating this image. Taken from slightly above the subject, the perspective of the image makes the man look diminutive in stature, as opposed to a lower angle, which would have made him seem large and powerful.

The areas of interest (i.e. the fish, the man, the turtle, and the net) are concentrated in the foreground of the image, while the background consists of a nondescript beach landscape. The colour palette is fairly consistent and muted, except for bold blocks of colour in the man’s clothing. His red shorts and blue shirt are a stark contrast to the taupe background. This draws the viewer’s eye first to him, and then, more significantly, to the sea turtle he holds in his hands. Framing is used on several levels – the fish and the net on the beach frame the man, while the man’s figure and bright clothing frame the turtle.

Finally, we consider semantics to examine the societal context of the image. The man’s smile and stance suggest a level of pride associated with the turtle, leaving the viewer to surmise his plans – is the turtle intended for a meal, or for release back into the ocean? We can make inferences about the man based on his clothing – he wears a t-shirt that is splattered with stains, and a pair of shorts with one pocket turned inside out. His unkempt clothing suggests that he has a job involving physical labour, as does his position next to the black net that appears to be used for fishing. The man’s attire fits in with his outdoor surroundings.

Captions have an important function in conservation photography, as they fill in gaps and help to answer questions associated with semantics. In this particular picture, the man is a Trinidadian fisherman, photographed with a juvenile green sea turtle caught in his fishing net right before he released the turtle back into the ocean. The photograph was commissioned by a sea turtle conservation NGO, intended to be seen by members of the general public in order to draw attention to the plight of sea turtles as by-catch in the fishing industry.

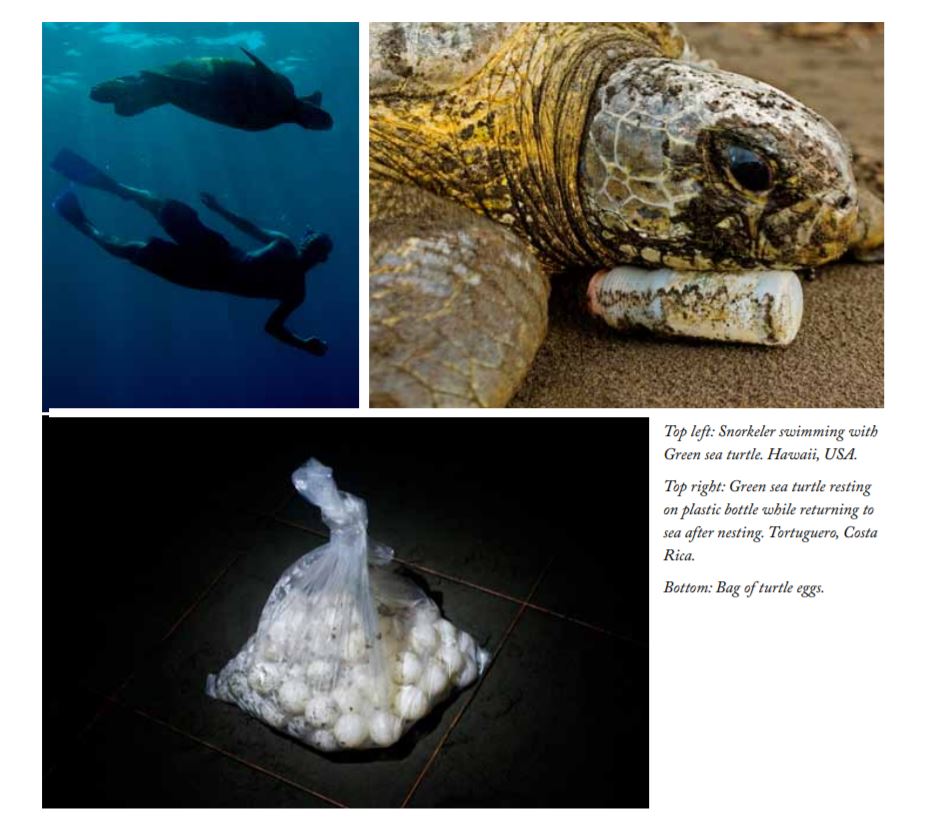

Quantifying the effectiveness of conservation photography is largely uncharted territory. In the following case study, we provide examples of outcomes resulting from the combined efforts of a biologist and a conservation photographer. Sea turtle populations are in decline worldwide, due to a number of causes including fishing practices, pollution, and ocean health. In an ongoing project to save these ancient reptiles, focused on specific populations, visual assets are being created for use in research, advocacy, and outreach, communicating the threats faced by sea turtles to the layperson and encouraging people to participate in conservation efforts locally. Partners onboard this international initiative include the California Academy of Sciences, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature Marine Turtle Specialist Group, among numerous conservation organizations. Grants and donations via The Ocean Foundation have brought the following outcomes to fruition:

- Print publications: photography used in magazines that reached a total circulation audience of over 5 million people to date, in both academic and mainstream audiences

- Presentations: photography used in worldwide presentations to audiences from 25 to 12,000 people

- Portfolio review: Mexican government officials are currently reviewing research findings on by-catch accompanied by documentary photographs

- Funding: increased donations, thanks in part to the impact and reach of conservation photographs.

The conservation photographer’s task is to disseminate images strategically, in order to promote their conservation agenda. Visually literate audiences have the skills to interpret these messages and by extension, the potential to make a difference through their actions. Therefore, a convergence is required between visual literacy competencies and conservation photography works.