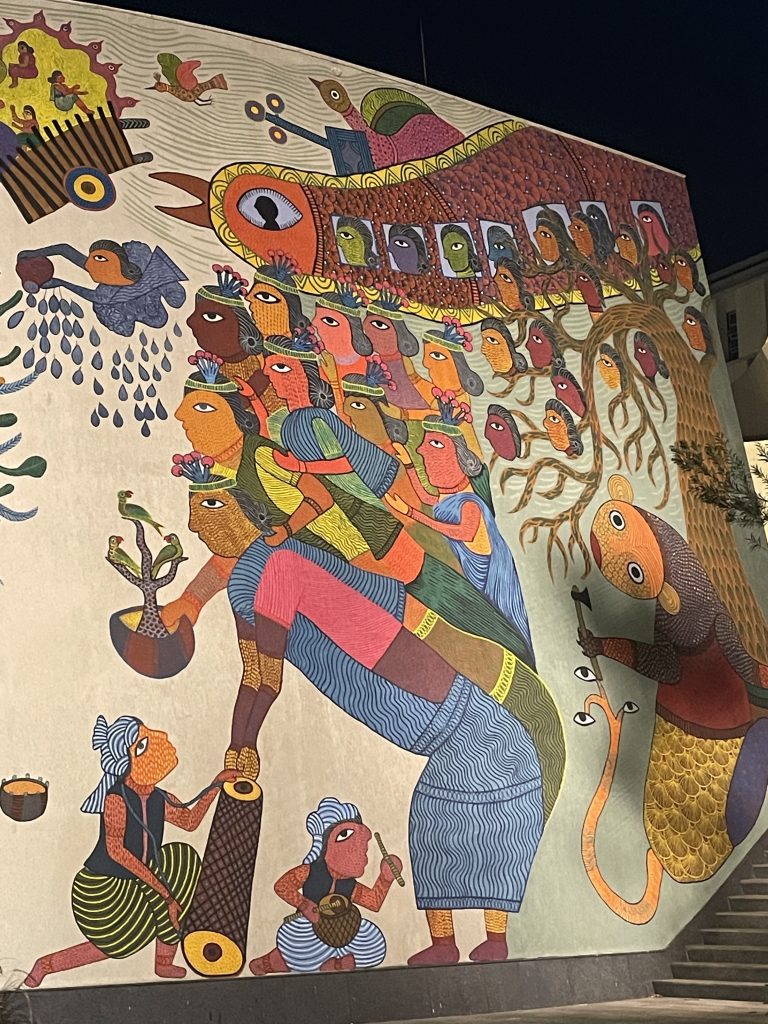

“A rainbow has seven colors, no one color is the same. A hand has five fingers, they’re all different. That’s the way of things. Banni is no different. No one monsoon is the same, no one year is the same, not every Maldhari is the same. Even the landscape changes all the time, it’s dynamic. That’s its way, Banni’s way. Our way.” – a Maldhari elder

I have spent a large part of the last decade studying Banni grassland for my doctoral work. It is a landscape that I have come to love for its veiled beauty, dynamism, and complexity. An arid grassland system, Banni is an important wildlife habitat spread across 3857 sq. kilometres in the Kutch district of Gujarat, India. The grassland has a unique community of 40 species of salt and drought-tolerant grasses. The landscape supports an array of Palearctic and Central Asian flyway birds—upto 273 resident and migratory bird species—serving as important foraging, roosting, nesting, staging and wintering grounds. Meanwhile, the grassland is among the few in the country where all four species of wild canids found in India co-occur. Banni is, therefore, ecologically quite significant.

The grassland is also home to centuries-old traditional pastoralist communities, the Maldharis (Maal = livestock, Dhari = owners). Known for their animal husbandry, the Maldharis have specially bred the Banni buffalo and Kankrej cattle that are drought tolerant, and are highly productive despite climatic vagaries. The Maldharis’ lives, identity, and economy is intricately tied to these vagaries. A good rain can boost the milk economy of these communities, and an above normal rainfall can lead to floods, displacing people and animals alike. A single drought can affect income for the year, whereas a prolonged drought can force members of this now semi-sedentarised pastoralist community to sell their livestock, migrate, and have lasting effects on the wellbeing of poorer pastoralists. These challenges, however, are not unknown to pastoralist cultures that are built around scarcity. A major reason why pastoralism has persisted for as many centuries, lies in the ability of pastoralists to adapt and sustain diverse environmental and social challenges. The Maldharis are no exception to this. Nonetheless, Maldharis are quite vulnerable—as are the grasslands they depend on.

“Banni is now changing, has changed. It changed when things around us changed. The land changed. The people changed. Our traditions have also changed. As pastoralists, we’ve changed. Is change negative or positive? We’ll know, probably. It will depend on how close or far we are from that point.”

Despite its resilience, the Maldhari way and the grassland is showing signs of wear and tear. Colonial regime, market forces, and privatisation, along with extreme climatic conditions (that are typical to this arid system) intermingled with climate change, have heightened a sense of vulnerability in this deeply entwined human and natural system.

How exactly, you may wonder that the ghost of colonialism haunts conservation management approaches of grasslands, and by extension, its people—the pastoralists.

Let’s rewind back to circa 1860 when the Indian Forest Department was created, to address concerns for the denuded state of Indian forests from overharvesting of timber, and leading to the introduction of scientific forest management across the British Raj. With revenue generation as the principal goal of this department, forest resources began to be ‘conserved and protected’. Forests provided timber, and timber was a valuable resource that drove colonial expansion. Meanwhile, grasslands, devoid of timber, were categorised as ‘wastelands’.

Common to forests and grasslands, however, was the exclusion and criminalisation of forest-dependent communities and pastoralists from these landscapes. This categorisation was also a reflection of the colonial viewpoint of pastoralism as a pre-agricultural, primitive way of life that needed to be sedentarised and integrated with agriculture.

Colonial records describe the province of Kutch as a ‘bare country’ with no trees. The rulers of Kutch, who were completely aligned with colonial power, remedied this situation. They created forests with drought-resistant trees, existing forests were heavily guarded, and grasslands, locally called rakhals, were closed off to prevent grazing, taxes were imposed to regulate grazing and livestock impounded. Partly used as game reserves, rakhals were used as grass farms that fed the royal stables, and were sites of extensive reforestation policies.

The new policies saw a permanent change in pastoralists’ relationship with natural resources. Villagers and pastoralists resented these new policies, and several Indian papers of the time were reported to have criticised the Maharao for prioritising his ‘passion for wildlife over people’s needs’. Over time, these policies were normalised, but this new normal also presented new problems. The protection offered to the animals within these ‘artificially preserved’ spaces led to complaints and accusations from people and local leaders that ‘panthers, wild pigs, and deer’ were steadily working their way through cattle and crops. Gaming rules were relaxed, meaning that rakhals were also thrown open to wild grazing, with the effect that indiscriminate hunting led to an alarming decrease in wildlife. This in turn led to the reinstatement of previous regulations—only tighter.

This must sound familiar, right?

After the accession of the princely rule to the Republic of India in 1948, forest management policies from the colonial era continued. Banni was primed for the same afforestation policies that were broadly considered successful in other parts of Kutch. Under independent India, pastoral communities not only had to contend with a fully ingrained wasteland discourse and related policies that barely accounted for pastoralist challenges and realities, but they also had to contend with the loss of traditional rights.

As a wasteland, the administration of Banni was under the Gujarat Revenue Department. But after being declared a Protected Area in 1955, the administration also came to be with the Gujarat Forest Department. This puzzling arrangement continues to this day. Banni is managed by both departments, which makes it a grassland, a wasteland and a protected area, all at once! And, because these are legitimate categories in government records, the battle for community rights under Section 3(1)(i) of the Indian Forest Rights Act (2006) remains unresolved to this day.

Despite the resilience of this centuries-old pastoralist system, the increasing fear of eviction has already strained the traditional patterns of resource sharing. Moreover, lingering uncertainty over the future has pushed several villages inside this grassland to privatise this commons land, raising tensions among the Maldharis. When the Maldhari elder remarked that not all fingers on a hand were the same size, he was referring to the embedded diversity of the landscape. Banni is made up of 19 panchayats and 54 villages with 21 different pastoral communities that are grouped under this one Maldhari identity. These communities are diverse in their social classes, family sizes, livestock holdings, a range of income sources, and a host of responsibilities that make up the tapestry of each household. From uneven development to unequal access to government relief measures, these 21 different communities have to contend with a diverse set of circumstances. The wear and tear is beginning to show in how the commons land is viewed in Banni now.

“Under the forest law, boundaries were drawn where none previously existed. We have no rights, we are strangers in our own land. Banni is ours. We have been here for centuries. Why should an outsider—like these private companies—occupy our land? Why should the Forest Department restrict us? If we don’t privatise it, these people will. Otherwise, we will lose it all.”

A sentiment that is widely shared by several old and young Maldharis. With the question of rights, or lack thereof, looming large over the landscape, there has been an alarming rise in privatisation of the landscape. Redirection of commons to rainfed agricultural parcels or tourist resorts (that service the annual winter festival— the White Rann festival) has affected the traditional ties that bind this heterogeneous community. This is evident from the counter claims of three panchayats that would prefer revenue rights, rejecting claims for commons.

But alas, Banni is a protected area, and non-forest activity is not permitted. So, a bid was made in 2018 to halt privatisation or ‘encroachment of forest land’ by filing a case against the encroachers with the National Green Tribunal in 2018—a Banni vs. Banni situation. The following year, the Tribunal ruled against the encroachments and ordered the immediate removal of all non-forest activity. While there was celebration that Banni is finally being recognised as a forest land and the Maldharis well on their way to get their rights, ugly scenes of conflict between the Forest Department and people were unfolding across Banni over removal of the encroachments, and revival of enclosures that would keep people out. As Karl Marx once said, “History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce.”

This unending sequence of events lead me to ask the question: whose grassland is this anyway? Maldharis’? Revenue Department’s? Forest Department’s? Or the wildlife?

Tellingly, conservation concerns have taken a backseat. If conservation needs to be addressed, then the locals need their rights to facilitate co-existence. But in continuing to alienate them, Banni has become another site where conservation goals remain elusive. Is there hope for the grassland, this unique yet frustratingly complex system that several of us love? Perhaps. Instead of making the sweeping generalisation that local people are always the best custodians of a landscape, I would say that they remain the best bet in the absence of more successful, cohesive and inclusive approaches.

And it’s about time we trashed that wasteland discourse!