On a bright sunny afternoon, after all the boats have come in for the day, a group of women fishers in a fishing village in Tamil Nadu sit around a pile of ‘trash’ fish. This is the catch, comprising a large number of invertebrates and non-edible fish, that will be dried and sold as animal feed and for fertilizer, but these women make a last-ditch attempt to sort through this fish to salvage what little they can. One of the women, Amutha triumphantly holds up a couple of seahorses and says, “This will help me buy some tea and snacks for the day”.

For people like Amutha, finding stray seahorses means some extra income for the family, while for the men, it usually covers the day’s alcohol and beedis. A trader comes in every day to buy all the seahorses they have collected (along with conches and other protected species that have gotten caught in their nets). It is a quick exchange, where the trader calls the shots. The fisher has no say on the price he or she will get for the seahorses, and they typically do not know what it is used for, other than the fact that it goes “to foreign” for some medicine.

It is very difficult to imagine that the seahorse, which is so casually traded for a pittance, is afforded the same protection by Indian law as the tiger.

What is the seahorse, and why should we care about them?

The seahorse is a strange-looking fish. They have a head like a horse, tail like a monkey, a kangaroo-like pouch, and eyes that move independently like a chameleon. Seahorses belong to the genus Hippocampus (from the Greek words for horse (hippos) and sea monster (campus)) and to the same family (syngnathids) as the pipefish. Seahorses are probably best known because, unlike most animals, it is the male that gives birth.

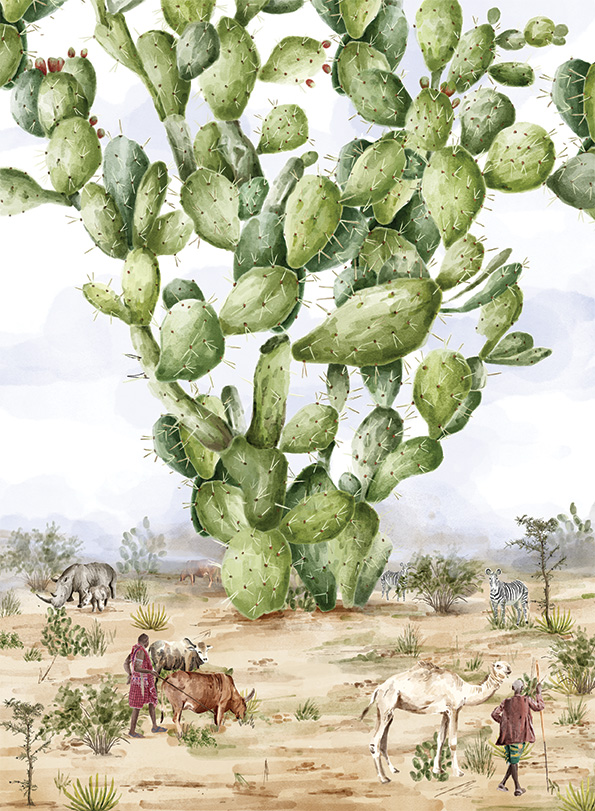

Seahorses are marine species, found amongst seagrass beds, mangrove roots and coral reefs, although some species are suited to dealing with varying salinity and are able to survive in estuaries as well. Seahorses manage to survive in their environment thanks to ability not just to change colour, but also to grow skin filaments and blend in with their surroundings. They use their camouflage, and flexibility to evade predators, since they are not the fastest of swimmers. In fact, the dwarf seahorse is considered to be the slowest fish in the sea.

While they are able to evade predators in the wild,seahorses face a major threat from overfishing and habitat degradation. Most often, like in Amutha’s village, seahorses are caught incidentally in fishing nets, which means that they are not the main intended species of the fishing expedition, but are caught as a result of indiscriminate fishing gear.

This has led to a worldwide decline in seahorse numbers. Globally, there are 44 identified species of seahorses, of which 14 have been listed as threatened, two as endangered, and 12 are vulnerable by the IUCN’s (World Union for Conservation of Nature) red list of threatened species, which assesses the extinction risk of species. There is not enough data to assess the status of about 17 of these species, while 11 are listed as ‘not threatened’. However, a recent study seems to suggest that at least nine of the 17 species for which there is not much data may also be threatened. In India, there are currently seven known species of seahorses in India, of which six have been listed as vulnerable and the seventh species has been assessed as data deficient.

There are a number of reasons why it is important that we understand how to conserve seahorses, and how the understanding can help improve our policies for marine conservation in general.

The threats faced by seahorses are the same that most other marine species face, including the degradation of their habitat, over exploitation, and being caught as bycatch. This has made seahorses flagship species for researchers to explain the need for marine conservation. Not only do they look extremely cool, they are also important players in the maintenance of the marine ecosystem, since they feed on organisms that live on the seafloor. Understanding the rampant exploitation and international trade of seahorses, and the fate of other incidentally caught species, can help strengthen legislation, and could go a long way towards protecting our marine environment.

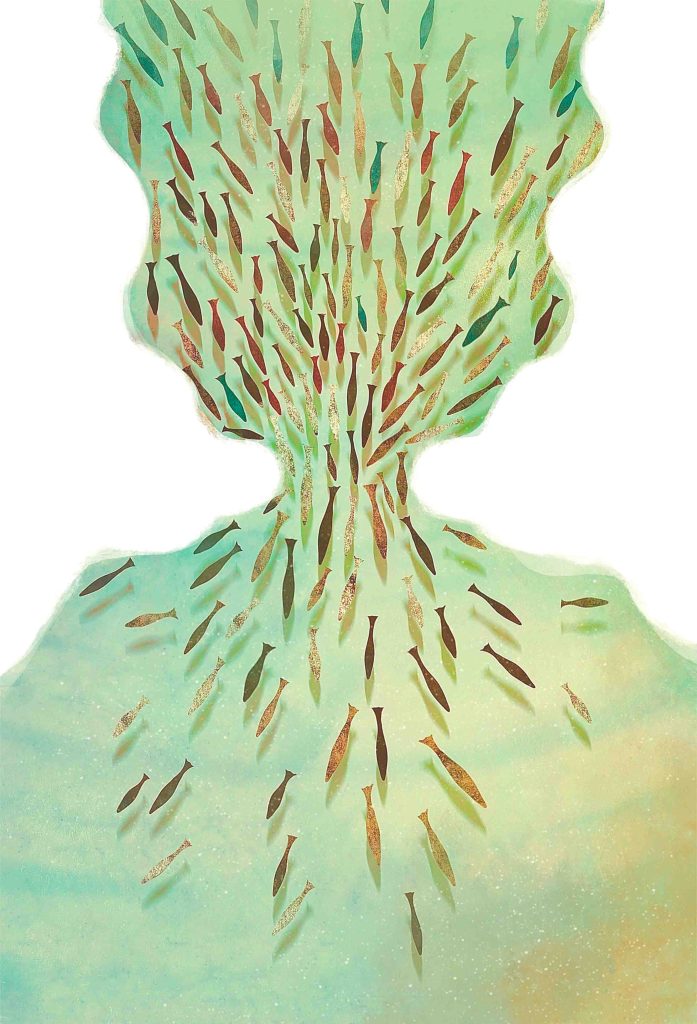

The global catch and trade of seahorses

Seahorses are mostly an incidentally caught fish. This means that fishers typically do not set out to catch seahorses, but they are often caught in the nets of bottom trawls, where a net is dragged along the seabed, impacting nearly everything in its path, and is the most destructive fishing method used globally. Thousands of non-target species are caught using this method, and large areas of marine habitats are destroyed. Typically, bycatch from these bottom trawls include seahorses, sea cucumbers, and a large number of other species. This indiscriminate fishing is believed to contribute to the capture of at least 37 million seahorses each year, and it is believed that a large number of seahorses caught as bycatch enter into seahorse trade.

Traditional Chinese Medicine is one of the main drivers of the trade of seahorses, since seahorses, in the dried form, are believed to cure conditions like baldness, asthma and arthritis improve sexual performance. Live seahorses are also in fairly popular demand and are traded for use in aquariums. Often, seahorses are sold as curios as well.

Despite a declining population, the trade continues to be rampant. Millions of seahorses are traded every year, and it is estimated that between 20 and 25 million seahorses are traded around the world every year. The demand for seahorses, and their declining populations led to seahorses being listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Flora and Fauna (CITES) in 2002. This was seen as a means to regulate exports and ensure their wild populations remain intact. CITES is a Multilateral Environmental Agreement (MEA), and is the biggest and oldest wildlife trade convention that aims to regulate international trade of animals and plants.

Seahorse fisheries and Trade in India, and the ban.

Until 2001, India was among the top four exporters of seahorses. But what changed after? To combat its substantial and unregulated seahorse fisheries, in 2001 India included all seahorses (and pipefishes) under Schedule I of the Indian Wildlife Protection Act which signifies a ban on the capture and trade of these species. However, being a small, bycaught marine species, they often come up accidentally in nets and then can easily fit into a pocket or the pallu of a sari, and the enforcement of the ban is much tougher.

In mainland India, till the ban, most of the seahorses in international trade were caught from the south- eastern coast of the country, from the Gulf of Mannar, and the Palk Bay, located in Tamil Nadu. While some of the seahorses were from targeted diving, a large number were incidentally caught using non-selective fishing gear. In addition to the large number of trawls operating in this region, seahorses face additional pressure from traditional but non-selective fishing methods such as the “Thallu madi” or drag nets. These nets, prevalent in the Palk Bay region of Tamil Nadu, are dragged along bottom-habitats in shallow waters directly over seagrass beds, and though often wind operated, are responsible for the catch of millions of seahorses.

While plenty of fishers continue to catch seahorses, fishers complain about declining fish catches, and many traditional fshers been severely impacted. For example, the divers who are not able to catch seahorses anymore but are losing out to the labour on trawler boats, who are often not even from the fishing community.

Although it has been fifteen years since the ban on catch and trade, what is clear is that seahorses continue being caught and traded in large numbers illegally. The demand for seahorses remains steady, and the prices received by traders for seahorses also increasing, which makes conserving the species even more challenging.

Do we need a change of tactic?

Project Seahorse has been working extensively to try and understand the impact of the ban on the catch and trade of seahorses. What we found is that India’s ban on catching and trading of seahorses has in no way ended their extraction, just as so many other wildlife trade bans (e.g. elephants) have had little impact for conservation. The ban is rendered more ineffective because of the rampant indiscriminate fishing in the country. Seahorses that are accidentally caught in the nets are often dead by the time that fishers sort their catches or reach the shore.

In the words of one of the fishers, Vellaiappan, “We cannot regulate catch in the ocean, and cannot control how much we catch, and cannot release seahorses once we catch them”. Instead, he advocates for the removal of the ban so that the fisherman can fish without fear.

The ban on seahorses is further undermined because of the poor communication to the fishers about the ban. After nearly two decades of the ban, what we found was that most fishers, and even officials, outside the state of Tamil Nadu were even unaware of this ban. Fishers in other states often would speak of other banned species, but not of seahorses. For example, in Gujarat, fishers would talk about the ban on whale sharks, but did not seem aware of the seahorse ban. In Kerala, on the other hand, there is a widespread belief that the ban only applied to Tamil Nadu fishers, and not to them.

Education and awareness often prove to be ineffective, since the question of livelihood is at stake. As one fisher from the Gulf of Mannar region of Tamil Nadu puts it, “Once the seahorse comes up dead, what is the point of throwing it back into the ocean? We may as well make some money from it.” For the fishers, the profits from selling seahorses are minimal, and they are often at the mercy of the trader, who determines the prices.

In the years after India banned its’ seahorse catch and trade, a number of countries such as Thailand and Vietnam because of their inability to manage seahorse trades at sustainable levels have since banned the trade of seahorses.

However, recent estimates suggest that around 95 per cent of the dried seahorses found in Hong Kong’s large market are reported to have come from countries like Indonesia, India, Malaysia, Vietnam, Philippines and Thailand, all countries that have banned seahorse trade. This begs the question, is the ban effective? Many governments find that it is easier banning the trade of seahorses than actually having to develop actual measures to ensure the conservation of these species. Till date, the focus has always been on the trade of seahorses. However, given that seahorses are typically incidental catch, it may be more effective to focus on preventing the extraction of seahorses from the ocean.

Rather than focusing on the ban of extraction and trade of specific species, what needs to be done is to phase out destructive methods such as bottom. Controlling the kinds of gear used. or setting some restrictions on the time or place where fishing can happen, could help.

Until there is a concerted move to control the devastation caused by indiscriminate fishing, the trading of seahorses, and other banned species will continue. The trader who regularly visits Amutha’s village agrees. According to him, all the regulation must happen at sea. “As long as there are no regulations on catches of seahorses being caught at sea, we will continue to have business in these villages”.