Fishing is one of the oldest livelihoods in coastal areas. Marine fisheries have provided food, nutrition and livelihood security to coastal communities for centuries. Karnataka, a state along the south-west of India is one of the major marine fishing areas of India. Historically known as the “mackerel coast” it has a coastline of 300 km and a shelf of about 25,000 km2.

The state’s contribution to marine fish landing varies from 6% to 14 % annually. Karnataka has three maritime districts namely Uttara Kannada, Udupi and Dakshina Kannada with an estimated 298 fishing villages. Fisheries of the Karnataka coast supports the livelihood of more than 10 lakh people of which more the 3.5 lakh people are directly dependent. Today, fishing livelihoods are not limited to a particular community or caste group as it has grown as an industry sector and contributes 1.1% total GDP and 5.15% to agriculture GDP.

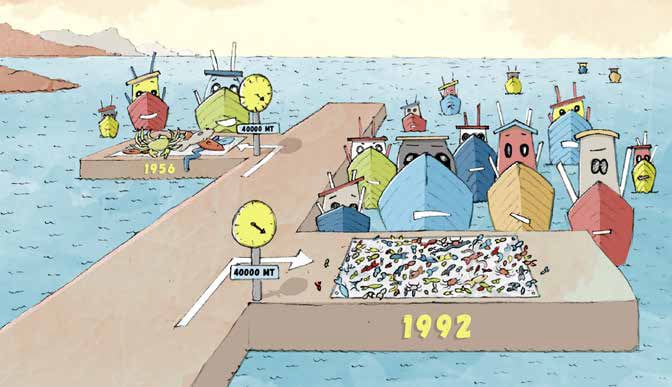

Prior to the 1950s, fishing was carried out by traditional practices using cast net, rampan net without the use of motor boats or mechanized gear. The introduction of an Indo- Norwegian Project in the 1950’s is held as the beginning of the modernization of Indian fisheries. Trawlers were introduced in 1962 with specially designed nets. The introduction of more intensive fishing gear and the rising popularity of trawlers on the Indian coast resulted in a steep increase in marine catches in the 1970s and 80s. However, catch rates either stabilized or decreased by mid 1990s proving the condition of overfishing of marine resources. Studies indicated that except for a few species, the recovery is very little after the collapse and that about 69 % of species need conservation and management. Fisheries scientists suggested that over-exploitation of fish resources alters stock size and affects ecosystem functioning through successive removal of top predators and large fishes.

This article outlines the scale and impacts of illegal fishing practices along the Karnataka coast and specifically in Uttar Kannada district. This is a direct result of scarcity caused by trawler-led overfishing and compounded by the non-compliance of fishing regulations introduced to regulate the sector. It also focuses on the start of efforts by artisanal fishing unions to manage the conflicts caused by illegal practices and make regulation effective for the prevention of these conflicts. Their efforts are an initial step towards socializing the regulatory framework for fisheries, so that these regulations produce the intended public benefits. Such a bottom-up review of regulation is needed to manage a resource that is vulnerable to the known and lesser known risks of climate change, global economic demands and regulatory capture.

Expansion of mechanized fishery and the failure of regulation:

There has been gradual increase in the number of mechanized boats that operate along the Uttar Kannada coast from 1957 – 1993. Before 1960’s the entire fishing was by traditional methods. Mechanized crafts were introduced in an unregulated manner from the 1960s. The total number mechanized crafts (purse-seines, trawlers and gill-netters) in 1975-76 were 371; it shot- up to 1333 in 1985-86, 1592 in 1995-96 and 2300 in 1999-2000. In the last two decades, there has been a threefold increase in mechanized boats in Uttar Kannada. It is interesting to see that the significant increase in the number of boats in Uttar Kannada did not show the increase in the fish landing. Fish landing has remained the same even though there is an increase in the fishermen population, number of vessels and effort. With the increased entry of mechanized crafts today, about 85% of the catch is captured by the mechanized sector, thereby depriving the traditional fishermen of their source of sustenance. Mechanization of the fisheries sector has not only pushed the sector to its ecological limits but has also caused immense distributive injustice.

To control this increased fishing effort, management tools such as Maritime Zones of India (Regulation of Fishing by Foreign Vessels) Act 1981, the Maritime Zones of India (Regulation of Fishing by Foreign Vessels) Rules 1982, and the State Marine Fisheries Regulation Acts and the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries at the global level etc, were implemented throughout the coastal areas at different points of time. The Karnataka Marine Fishing (Regulation) Act (KMFRA) of 1986 is one of the legislations implemented in Karnataka aimed at controlling the impact of fishing on the marine resources and also to manage the conflicts between traditional and mechanized fishermen.

The KMFRA, states that the government may regulate, restrict or prohibit the fishing in certain areas by particular kind of fishing vessels by notification. It also states that, the government can regulate by way of a notification the number of fishing vessels or specific species fishing in any specified area or a particular season. The act also says that the use of some fishing gear in any specified area as may be prohibited, regulated or prescribed. In making an order under this act the authority should protect the interests of different sections of persons engaged in fishing. This is particularly for those engaged in fishing using traditional fishing craft such as country craft or canoe and the need to maintain law and order in the sea. However, these regulations have not been implemented and the number of mechanized boats have continued to increase. Under KMFRA 1986, an order was passed in 1994, which states that 10 km from the shore in the west coast and 7 km in the east coast is reserved for traditional fishermen. This too has remained unenforced leading to direct conflicts between trawler and artisanal fishermen seeking to live off a dwindling resource.

Bull trawling in 10 km coastal area and resource conflicts

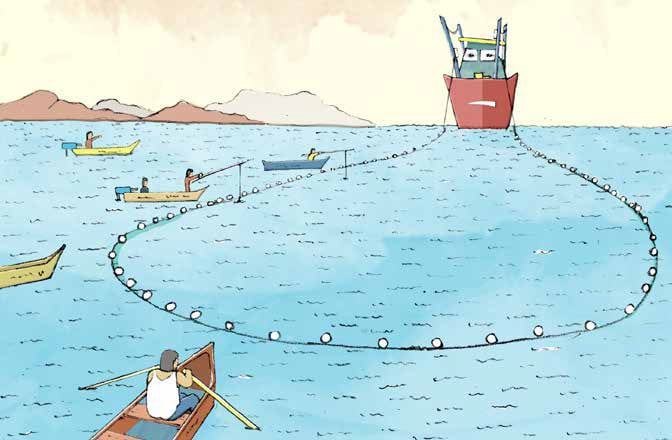

Reduced fish catch due to technology driven overfishing practices and the failure of implementation of marine fisheries regulation has led to conflicts. Destructive fishing practices such as bull trawling and halogen light fishing are prevalent now. Increased availability of mechanized vessels have made more of these being used for bull trawling. Bull trawling is done with two trawl boats with engines of more than 300 hp, even though this is not permitted by the Department of Fisheries. One end of the tow rope is tied to one boat and the other end to the second so that it adds to the speed of the trawl operation.

This practice destroys the seabed because of its high speed and heavy otter boards which are tied at the end of the fishing net to make the net submerge in the water. This method of fishing is hazardous to bottom living fishes and other organisms. It damages fish eggs and juvenile fishes as well as the food of the fishes. Bull trawling has impacted benthic fishes, dolphins, turtles, sharks and skates and therefore the ecosystem.

It gets even worse when these bull trawls are operated near the coast (i.e. within 10 km limit). This destroys the livelihood share of poor traditional fisherman. In recent years the disputes between the traditional fishermen and mechanized fishermen have increased along the Karnataka coast and there have been several incidents where traditional fisher folks have filed complaints to authorities.

In order to study the nature of the conflict, focus group meetings with fishermen were conducted in 20 villages by the Uttara Kannada based team of the Centre for Policy Research (CPR)-Namati Environment Justice program. We spoke to 65 fishermen and visited 7 traditional fishing unions in the district. We asked them questions regarding recent fish landing trends, reason for variation, impacts of illegal fishing practices (bull trawling, night fishing, light fishing). We also asked questions to gauge their knowledge of the law to regulate fisheries, their earlier efforts to resolve the issues they face, complaints filed and response received.

During this research carried out between January 2014 to June 2014 and meetings carried out from June 2016 to January 2017 on the Uttara Kannada coast we found that bull trawling is the most destructive fishing practice affecting the livelihood of traditional fishermen. Most of the boats come from Mangalore, further south on the west coast, and engage in bull trawling in the Uttara Kannada. When bull-trawling operations are carried out near the coast, (within 10 km limit) the traditional fishermen return empty-handed. The high speed trawl boats disturb the shallow coastal water making it more turbid, so fishes and prawns migrate to other regions. Venkatesh Moger president of the Traditional fishing union from Bhatkal, says that because of the bull trawling the traditional boats do not get enough fish catch during the season.

Out of the 65 people we spoke to 37 people directly attributed this practice to the decline in fish catch. Among the remaining 28 people few people partially attributed bull trawling and also mentioned the added effects of night fishing and smaller mesh size. A few among them said that bull trawling may not be the reason for overall decline in the fish catch since it is carried out only for three months when the prawns are abundant (September to November). The remaining 12 people reported that fish catch is generally decreasing because of more boats and overfishing. Out of the seven unions we visited six union members held that bull trawling is the major threat and that it takes away the fish catch share of traditional fishermen. Only one union from Manki village was not sure about the role of bull trawling in the decline in the fish catch and said that it could be due to the increase in the number of fishing vessels.

As per the data collected from the interviews, group discussions and newspaper reports, there have been more than 34 instances of conflicts between traditional fishermen and mechanized fishermen because of bull trawling during the season of 2014 -2015. Traditional fishermen from Bhatkal had filed five complaints to the Department of Fisheries and two complaints to the trawl boat union in Mangalore, but no action was taken.

Unlike all the fishermen interviewed who discussed the issue of bull trawling as a matter that requires attention, the fisheries department was indifferent to questions posed to them about this practice. When we visited the Fisheries Department they said that there is no fishing practice such as bull trawling and they had not given permission for it.

In practice, once the prawn season is over by November, bull trawling also stops and the same boats are then used for normal trawling. The seasonal nature of these practices makes timely monitoring very crucial but the fisheries department does not have enough staff to monitor these practices.

Visits and discussions with the Fisheries Department offices in district revealed that there is no monitoring authority to oversee illegal fishing activities in Karnataka. They said that they could only pass an order or cancel licenses if they come to know of violations/illegalities. But, they do not have manpower to investigate these issues on their own, and it is not their duty to monitor illegal activities along the coast.

Bottom-up efforts to review fisheries regulation

The study clearly revealed that bull trawling is a threat for traditional fishermen and people have approached authorities for solutions. However, even though the activity could be prohibited exercising clause ‘a’ and ‘d’ of Subsection 1 under section C, of KMFRA, there is no order issued specifically mentioning on bull trawling. Therefore we worked with the fisher communities to see if the law can be reviewed. A carefully drafted demand letter was sent by the Bhatkal Traditional Fishermen Union (Bhatkal is an important fishing centre) to the Fisheries department to reiterate the need for a ban on bull trawling along the coast of Uttara Kannada.

In November 2016, the Directorate of Fisheries of the Karnataka State Government issued an order saying bull trawling is a violation of KMFRA and action shall be taken as per the provisions of the Act. This time the artisanal fisheries unions were aware of the legal framework since they had learnt the KMFRA, 1986 through the trainings conducted by CPR-Namati Environmental Justice Program.They also developed a format to file complaints on fisheries law violations using the provisions given in the KMFRA, 1986. As part of their efforts to bring the legal prohibition of bull trawling to life, the unions are engaged in continuous monitoring of fisheries violations, collection of evidence and filing complaints to bring the issue to the notice of authorities and seek specific remedies.

Following the trainings, recommendations for changes to the law and implementation mechanisms were drafted along with fisher communities. The main ones were the following:

- The Fisheries Department should issue an order under KMFRA to regulate the number of mechanized crafts that can be operated in a specific area.

- The KMFRA should also include conservation clauses for better management of fisheries. Currently, the law only mentions licensing of fishing vessels and a few restrictions according to season and gear type. Moreover, the department of fisheries aims to increase fish landing rather than conservation and management.

- For the effective implementation of these management measures, there is a need to understand the fishers’ perception by authorities and policy makers on the issues related to management of resources and involve them in monitoring, as they are the primary users of the resources. The Department of Fisheries had failed to implement the existing regulation because of insufficient manpower and absence of data on compliance and monitoring. This is despite submissions of complaints and evidence.

An opportunity to secure environment justice using marine regulations

The active involvement of fishing unions and artisanal fishers of Uttara Kannada in the legal training programs is the basis of their legal empowerment. An informed participation of the community and especially the unions can lead to their active role in the implementation of marine regulations and engagement with the fisheries department on the issue of bull trawling conflicts. Their interest in deliberating the clauses of the KMFRA offers a new opportunity for the review of marine regulations in the state. Such a review if done with collaboration of fisher unions will result in framing better and more evidence-based regulations that that respond to the issues of production and fair distribution of fishery resources. These two aspects are the essential ingredients of environment justice.

References:

Bhathal B and D Pauly. 2008. ‘Fishing down marine food webs’ and spatial expansion of coastal fisheries in India, 1950 – 2000. Fisheries Research, 91: 26 – 34.

Caddy JF and GD Sharp. 1986. An ecological framework for marine fishery investigation. FAO fishery technology paper, 283: 1 – 52.

Hutchings JA. 2000. Collapse and recovery of marine fishes. Nature, 406: 882 – 885.

Mohamed KS, C Muthia, PU Zacharia, KK Sukumaran, P Rohit, PK Krishna Kumar. 1998. Marine Fisheries of Karnataka State, India, Naga, the ICLARM Quarterly. NFDB. 2017. National fisheries Development Board, https://nfdb.gov.in/about-indian-fisheries.htm

Rao KV and K Dorairaj. 1968. Exploratory trawling off Goa by the Government of India fisheries vessels. Indian Journal of Fisheries, 15: 1 – 13.