In the quest for new knowledge, we often forget those responsible for much of what we know today. One such man buried in the annals of Indian natural history is Edward Blyth.

EARLY LIFE

Born in London on the 23rd of December 1810, Edward Blyth inherited from his father a keen love for nature and a remarkable memory. His father’s death, when Blyth was ten years old, plunged the family into poverty setting the stage for a life of hardship that never ended. His early schooling began in Wimbledon, where he was considered an exceptionally bright student, albeit not a well behaved one; the young boy was in the habit of wandering away from classrooms and into the woods.

IN LONDON

There was however the question of earning one’s bread and butter, as the study of nature was not a lucrative enterprise. So in 1832, after studying chemistry, Blyth took on a druggist’s business in Lower Tooting, London. Leaving the management of his business to others, he began to focus on his studies in natural history. Much of his time was spent trying to gain access to books and literature at the British Museum. He became a regular speaker at meetings of the Zoological Society in London. Unsurprisingly, his chemist’s business did not prosper under such neglect, leading to great financial difficulties. Five years later, he gave up his pharmaceutical career to focus on zoology exclusively. Despite monetary troubles, he began writing for journals such as the Magazine of Natural History and Field Naturalist while continuing to present several papers on birds and mammals at the Zoological Society of London. In 1840, at the age of 30, he had his first major literary accomplishment; contributions to the section on Mammals, Birds and Reptiles in Georges Cuvier’s mammoth Regne Animal (Animal Kingdom). His familiarity with Indian fauna began long before he ever set foot in the country. At the Zoological Society meetings, he presented several illustrations and specimens of Himalayan ungulates such as the Yak (Bos mutus), Markhor (Capra falconeri) and Ibex (C sibirica). Particularly well known is his monograph on the genus

Ovis in which he described fifteen species of sheep, including a new subspecies of Argali (Ovis ammon). Blyth proposed naming this race the Marco Polo sheep (O a polii), after the legendary Venetian traveller who first reported them from the Pamir mountain ranges. It was around this time that young Blyth’s paths crossed with an institution that was to be both friend and tormentor for the remainder of his career.

The Asiatic Society of Bengal was established in 1784 by Sir William Jones as a centre for study of Asian natural history and culture; a vision that it promotes to this day. At the peak of the East India Company’s reign in India, several prominent naturalists such as Brian Hodgson and John McClelland regularly contributed specimens and illustrations to the museum of the Asiatic Society in Calcutta. However, with no experienced curator or funds to hire one, the collections were in disrepair. Blyth was by this time in poor health and had been advised to seek warmer climes. More importantly, he was eager to travel to a country whose fauna had long held his fascination. Although it did little to improve his financial condition, he accepted the offer.

INDIAN VOYAGE

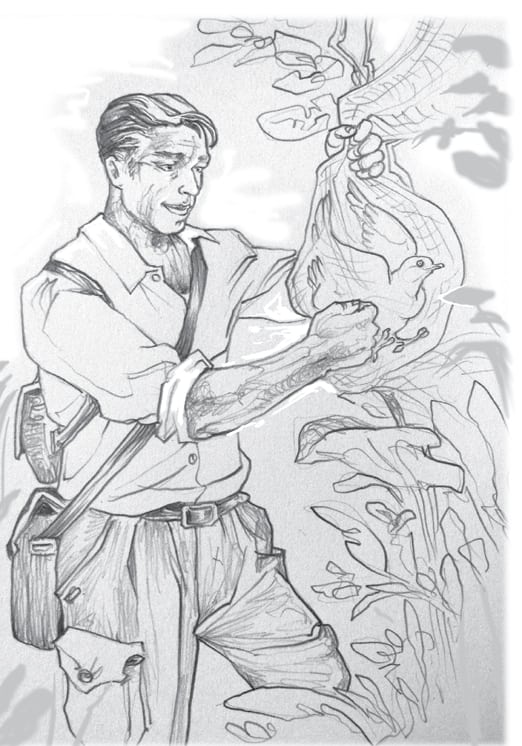

It was in September 1841 that he reached Calcutta and took over as the society’s curator. While at the Asiatic Society, Blyth described several new mammals such as the hangul (Cervus elephus hanglu), a subspecies of the European red deer and three species of Indian bats. His detailed notes on the many specimens he received and his ability to maintain open channels of communication with hunters who supplied him with these, helped increase the collections of the Society’s museum. However, Blyth’s attention to detail and meticulousness were often a source of great irritation to his colleagues. According to Arthur Grote, Blyth’s magnum opus Catalogue of Birds and Mammals of Burma was only published posthumously owing to his habit of constantly waiting for the latest possible information on the subject. In his memoir of Blyth in The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Grote mentions, ‘It had been constantly kept back for the Appendices, Addenda and Further Addenda, which disfigure the volume, and seriously detract from its value as a work of reference.’ Blyth also faced criticism for letting his passion for ornithology and mammalogy lead to the neglect of other departments. These allegations came even as he sought an increment in his salary in recognition of his contributions in increasing the collections of the Asiatic Society’s museum. Perhaps because of its dire financial conditions, the Society declined to change its salarial position citing the need to first investigate the complaints against him. Furthermore, he had a number of acrimonious disputes in public, including a sparky exchange with Brian Houghton Hodgson in the pages of The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. However, several naturalists of the time acknowledged his contributions, including Charles Darwin.

THE DARWINIAN CONNECTION

Between 1835 and 1837, Blyth had written three articles on variation in different species in the Magazine of Natural History, almost 24 years before Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species. Furthermore, it was Blyth who first sent to Darwin Alfred Wallace’s paper ‘On the Law which has regulated the introduction of Species’ that may have pushed Darwin to hurry with his publication. This led to much speculation about the originality of Darwin’s ideas; for instance the anthropologist Loren Eisley suggested in his book Darwin and the Mysterious Mr X: New Light on the Evolutionists that Blyth had developed ideas regarding selection in animals (if artificial rather than natural) much before Darwin, by studying variation in domesticated animals. A respected authority on the subject of artificial selection or domestic breeding, Blyth had corresponded with Darwin several times about the subject. However, several historians and evolutionary biologists such as Stephen J Gould, Ernst Mayr and Theodosius Dobzhansky discredited Eisley’s thesis and argued that Blyth, like other creationists of the time, believed variations in species were only certain imperfect forms that did not have the ability to survive, unlike the original perfect forms created by divine intervention. Darwin on the other hand saw variation as a continuous process where each new form was a step in evolution. Blyth’s contribution was however valued by Darwin as is evident from the very first chapter of the Origin, where Darwin expressed his gratitude for Blyth’s contribution of considerable information on plants and animals in India. Darwin wrote in his book, ‘Mr Blyth, whose opinion, from his large and varied stores of knowledge, I should value more than that of almost any one….’

FINAL DAYS

In 1857, Blyth’s short marriage ended with the death of his wife. This perhaps was the beginning of his decline. Although still an active writer and naturalist, his personal life began to disintegrate. He suffered from what appears to be depression, and soon took to alcohol. In 1865, after a nervous breakdown he formally retired from the Asiatic Society and left to be tended by his sister in England. During his time in India, he had described 21 new mammals and several species of birds. While in London, Blyth kept up active correspondence with the Zoological Society and continued to write several articles under the pseudonym Zoophilus. He was conferred with honorary membership to the Asiatic Society and elected Extraordinary Member of the British Ornithological Union. His personal life, however, was in stark contrast with his professional achievements. He was convicted for assaulting a taxi driver in London, under the influence of alcohol. In December 1873, at the age of 63, he succumbed to heart disease.

Edward Blyth lived a life of difficulty, but also one of discovery and learning. He expressed this best in his introduction to the 1836 edition of Gilbert White’s Natural History of Selborne: “my mind cleaves to its favourite pursuit in defiance of many obstacles and interruptions, and eagerly avails itself of every occasion to contribute a mite to the stock of general information.”

Suggested reading:

Arthur Grote. 1875. Memoir and portrait of the author (Edward Blyth), in Catalogue of the mammals and birds of Burma.

Christine Brandon-Jones. A Clever, Odd, Wild Fellow: The Life and Work of Edward Blyth, Zoologist, 1810-1873 (Madras: Madras Snake Park Trust, 2006).