I had to squint against the afternoon sun to see the outline of the Vizhinjam International Seaport that was under construction. A couple of my coursemates and I were on our way to meet with local artisanal fishermen in Trivandrum, Kerala.

“Palli-de avde ethittu, vilicha madhi, njan veraam.” Call me when you reach the mosque, I will come there.

Our interview facilitator sounded very patient over the phone as we meandered around the harbour, trying to locate the mosque.

A quarter of an hour later, we were in the company of nonchalant fishermen who had finished the day’s work and their lunches. Our facilitator informed us that conversation was welcome at this point.

A coursemate and I had undertaken a short field study to understand the impacts of the Adani port construction on the livelihoods of artisanal fishermen at Vizhinjam. This was a part of a wildlife and habitat conservation course that I was doing with an NGO based in Coimbatore. The theme of the course was marine conservation and its challenges, which brought us to the coasts and communities of Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

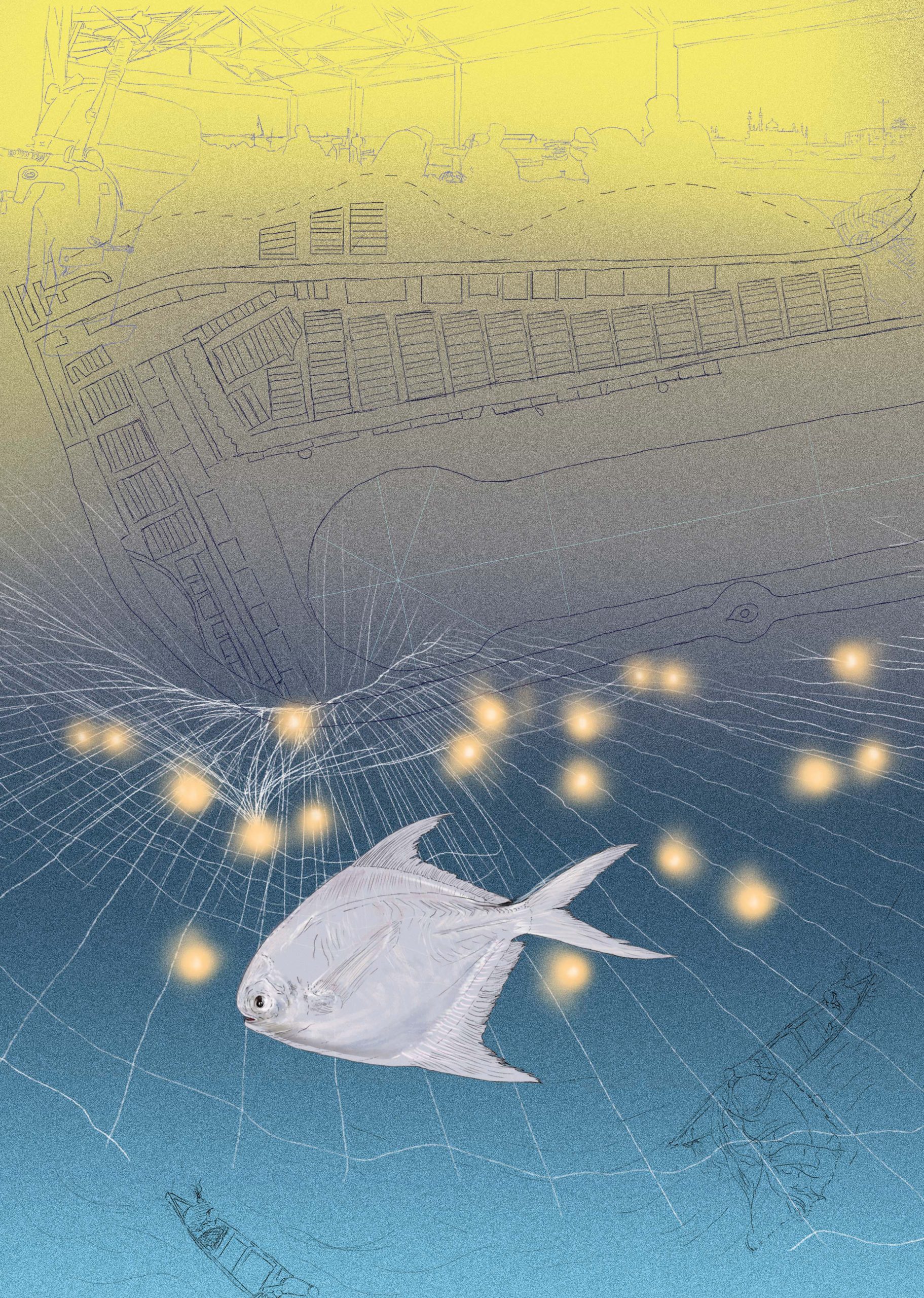

I was nervous about conducting interviews with the artisanal fishing communities because this came on the heels of some of them violently protesting against the construction of the port about a month earlier. Their gripe was that the port would result in higher rates of coastal erosion, lower catch, and community displacement. My desk research confirmed the chronology of this issue, while also throwing up various scientific, political, religious and social perspectives. Most of the news articles were accompanied by the image of the larger-than-life structure of the port sitting where it really did not belong—in the backdrop of numerous colourful fibre boats and the mosque that was our present landmark.

This would be a very sensitive subject to broach, so I consulted my professors and went through my survey questionnaire repeatedly to ensure I would not cross a line. I exchanged apprehensive introductions with my first interviewee and got down to business.

“So, has anything changed for you after the port construction began?”

Fighting reality

The word ‘development’ has many interpretations.

In 2015, the verdict to modernise India’s ports was passed through the National Perspective Plan. Called Sagarmala, the vision of the project was to develop the nation’s logistics infrastructure for seamless trade. In southern India, Vizhinjam was one of the many national sites planned for port modernisation.

Vizhinjam is approximately 16 kilometres south of Trivandrum, stretched between Kollam and Kanyakumari, and lies close to major shipping routes. The port construction project was envisioned as a Public-Private-Partnership and the harbour was chosen for development, primarily because of the geomorphological features of this region—Vizhinjam has a natural bay, with a depth of 18-20 metres that would allow the parking of capesize vessels (the largest cargo ships) without additional dredging.

Vizhinjam is home to artisanal fishing communities like the Mukkuvars, who rely on the sea and its bounty for daily living. The seabed in and around the area has rock formations, sandy bottom ridges, floor slopes and sloping ridges, making the space a rich breeding ground for mussels and a variety of marine organisms.

I asked some of my interviewees what ‘development‘ meant to them. They defined it as having enough to eat every day and meeting educational expenses of their children so that in the future, they may take up an occupation apart from fishing.

This is because finding catch in and around Vizhinjam is getting increasingly difficult as port construction milestones are ticked off on a Gantt chart.

Turn of the tide

Artisanal fishermen use sustainable methods of catching fish as opposed to trawling and gillnet fishing that sweep out species from the seafloor. Some of the most popular regenerative fishing methods at Vizhinjam are hook and line fishing (chunda), trammel nets (konchu vala), boat seine (thattumadi) and variations of these. Chunda is used to catch tuna, groupers and snappers, whereas thattumadi is used to trap squid, ribbonfish, pomfret and other targeted species.

These methods are regarded as sustainable for it allows fish populations to recover in numbers before the next fishing cycle. Also, the chances of trapping bycatch—non-targeted species—is minimal due to the fishing gear deployed.

The coast of Trivandrum experiences another phenomenon—erosion and accretion. Erosion typically occurs along the northern coast while accretion happens in the south. There are natural checks and balances, but artificial structures such as groynes, reclamations and reefs, interfere with the process, causing disruptions in sediment flows.

Mr. Das (name changed), who fishes about 30 km north of Vizhinjam says that since construction began, he and his friends have visually observed an increased rate of erosion. This has forced them to move their landing centres closer to the mainland.

Regular dredging at the port mixes sediments and leads to muddy waters, which keeps certain fish species away. To add to the problem, there are lights within the construction perimeter that are kept on all the time. According to the men, these lights deter the fish away from the coast as it increases visibility of their fishing gear. This, in turn, has created many disruptions in the way they have to fish.

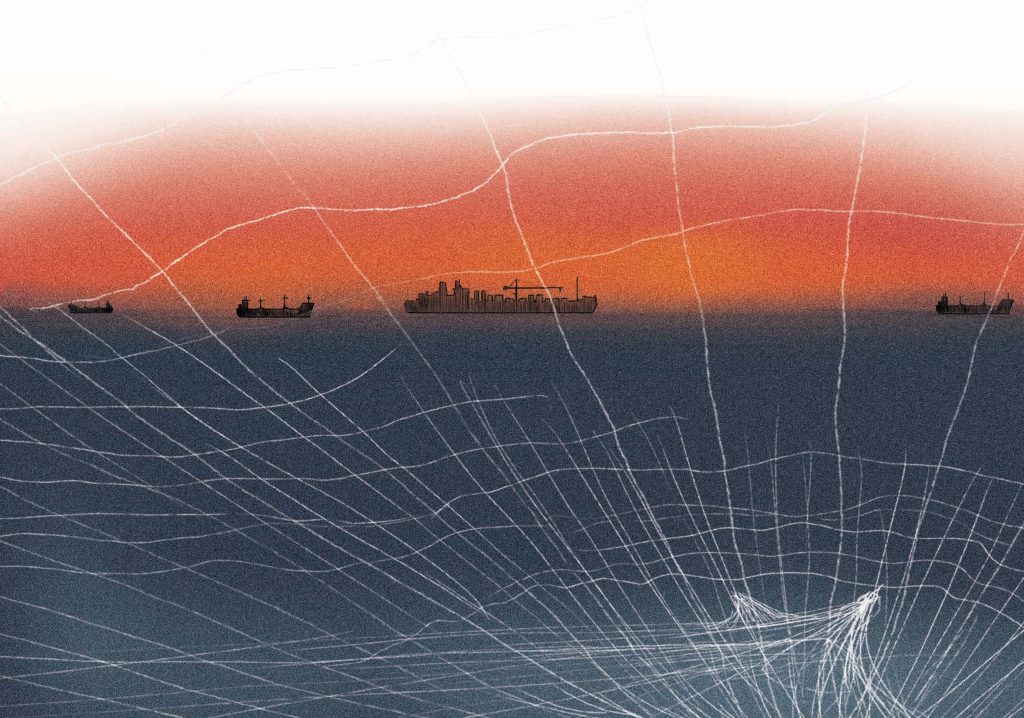

Mackerel, tuna, sardines and seer fish are the main catch at Vizhinjam. Previously, these were procured within a distance of 5-10 km from the shore. Now, the average distance travelled for a decent catch is 15 km. Even with subsidies, diesel and kerosene are pricey, especially during periods of low or no catch. In addition to altering their own fishing methods, prevalent destructive practices such as trawling and light fishing put them out of the game by reducing their catch quantity and composition.

Things look bleak on the mainland as well. The upcoming construction work in the hinterland to build port connectivity will impact the fisherfolk living by the shore. In an interview with a retired fisherman at Adimalathura, a 30-minute drive from Vizhinjam, he mentioned that massive boulders had been dumped at Chappath, a town close to Adimalathura. These structures occupied a minimum area of 200 acres by his estimation. The land was being cleared to make way for roads leading to the National Highway 66, which connects major seaports situated in western India.

My interviewees mentioned the blatant apathy from the government in dealing with the matter of community livelihood and displacement. Fisherfolk were instructed to move to a warehouse with a cramped living space of 10m x 10m, a significant downgrade from the housing spaces they were used to. The non-availability of basic facilities such as restrooms was of great concern. Proper negotiation channels were not opened to the community, which is what led to the protest at the end of 2022.

Nine out of 10 interviewees said that their children are either willingly opting for non-fishing occupations or are being persuaded to do so. The prime reason for this is the knowledge of depleting fish stocks in the sea. One interviewee knows how bad it is without even reading about biodiversity loss and climate change. Since the 1980s, he has observed that about 33 kinds of fish are not available to catch anymore.

Status quo

Public apathy sets in when there is a certain distance from the epicentre of an issue. While writing my project report, one of my recommendations was having local citizen programmes to build awareness on the livelihood threats to artisanal fishermen. At the back of my mind, I wondered if it is any good because the issue is being viewed through a lopsided lens by key decision-makers, leading to a disregard for scientific recommendations, a lenient environmental impact assessment report, and an indifference to concerns of the communities. All of this a great hit to the artisanal fishing communities and a massive step back for conserving marine species as well.

I fell silent after my last interview at Adimalathura. My interviewee’s concluding remarks echoed in my mind. “They paint us as villains of development. We are not. We only want to know why we are being excluded from development.”

I glanced at the Arabian Sea and noticed silhouettes of ships dotted along the horizon. I did not have to squint this time.

Further Reading

Pradeep, J., E. Shaji, C. C. Subeesh Chandran, H. Ajas, S. S. Vinod Chandra, S. G. D. Dev and D. S. S. Babu. 2022. Assessment of coastal variations due to climate change using remote sensing and machine learning techniques: A case study from the west coast of India. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 275: 107968.

Sahayaraju, K. and J. Jament. 2021. Loss of marine fish stock in south west India: Examining the causes from the perspective of indigenous fishermen. International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies 9(5): 23-29.

Shaji, K. A. 2019. Is the deep-water sea project in Kerala an environmental and livelihood threat?

https://india.mongabay.com/2019/08/is-the-vizhinjam-port-in-kerala-an-environmental-and-livelihood-threat/. Accessed on March 9, 2024.