“Ekul bhange okul gore,

Eta nodir khela”

(One side erodes, one side grows,

that is the river’s play)

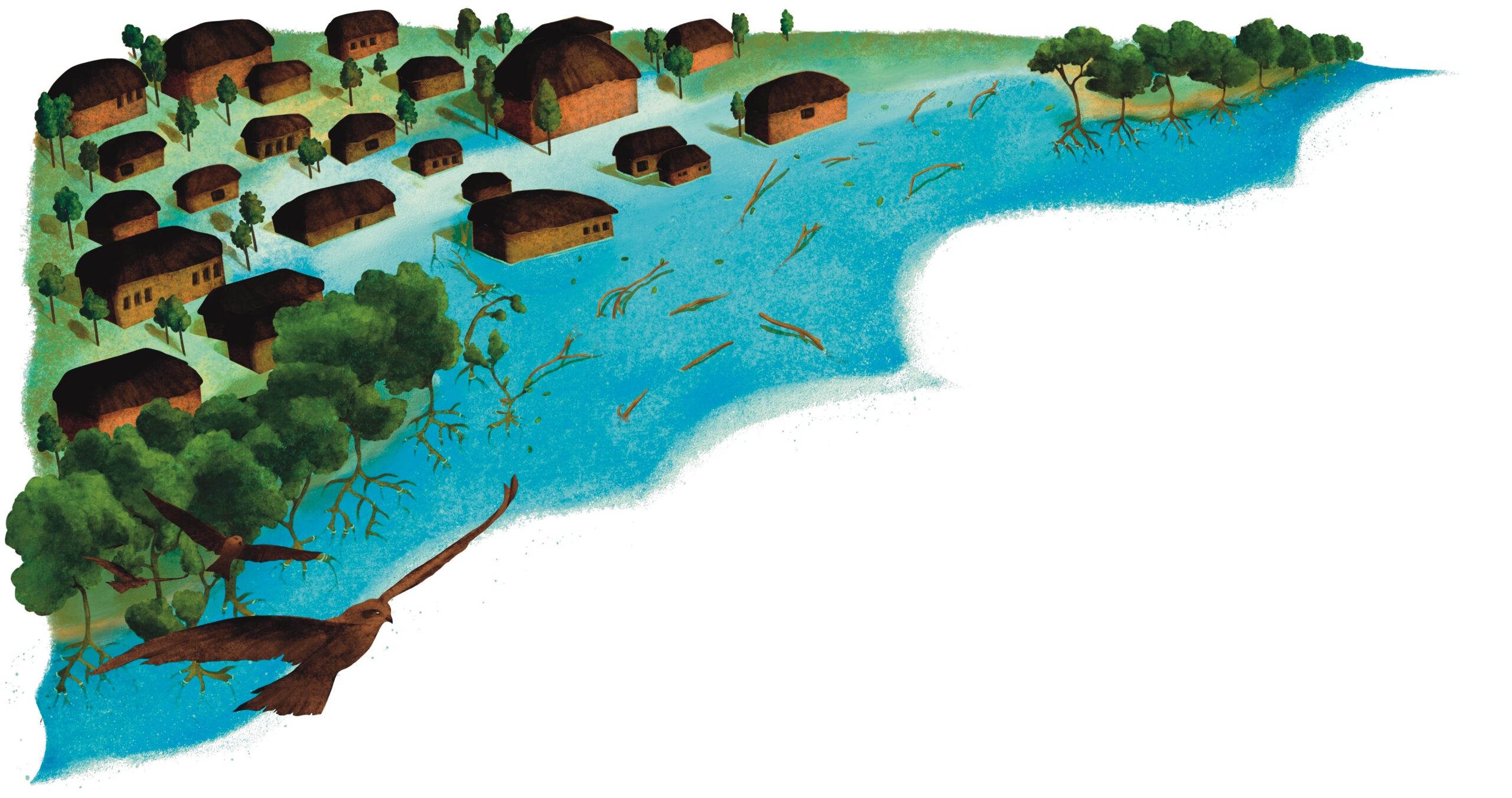

These lines about the Bengal Delta, penned by the renowned Bangla poet Kazi Nazrul Islam, play in my mind as I walk on a mud-paved path along the salty and turbid Matla River, overlooking mangroves on one side and a flooded village on the other.

The fluvial-tidal Bengal Delta is where the 10,000-km2 expanse of the Sundarbans mangrove forest comprising about 250 islands is located, straddling India and Bangladesh. The delta was formed by the erosion and accretion of a rich load of sediments brought by the Ganga, Brahmaputra, and Meghna Rivers originating in the Himalayas.

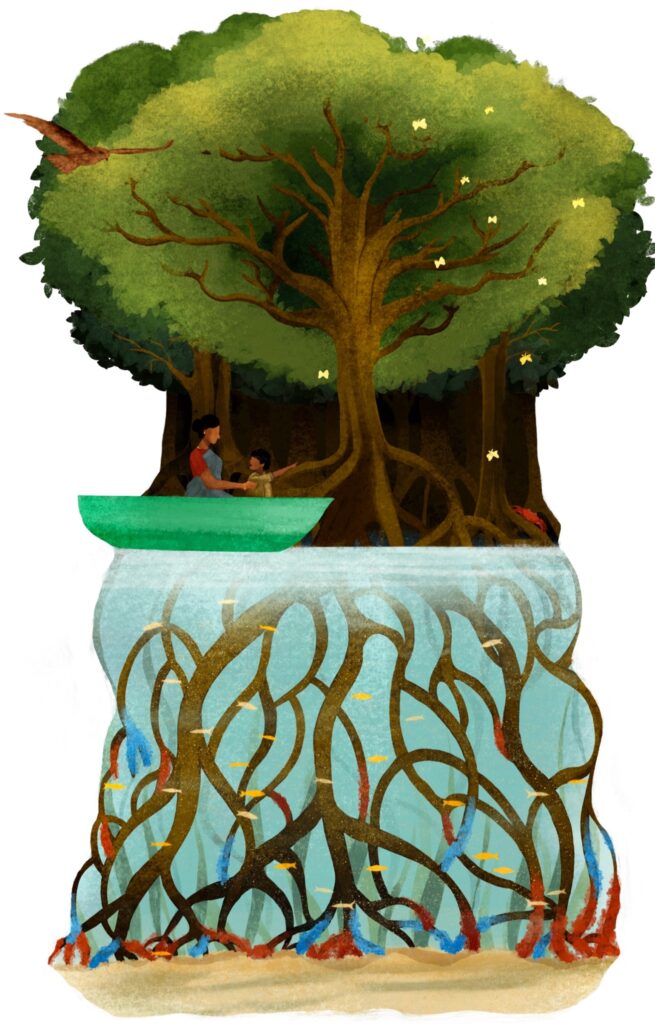

The delta shaped by these sediments is home to the largest contiguous mangrove forest, full of rich biodiversity and endemic species like the Ganges river dolphin (Platanista gangetica gangetica), the northern river terrapin (Batagur baska), and the only mangrove forest to host a tiger (Panthera tigris tigris). The sediments settling in the Bengal Delta and those flowing out to the Bay of Bengal and into the Indian Ocean tell us about the Sundarbans’ past, present, and future.

Creating a new equilibrium

Socio-ecological changes in the recent past tell us how the geography of the delta evolved. The first mass inhabitation of the Sundarbans began in the late 1800s, leading to the deforestation of mangroves and the introduction of agriculture to the muddy wetlands.

However, at the periphery of the islands, 1–2 km of mangrove forest area was always kept intact by settlers. This helped prevent the impacts of flooding, tidal surges and extreme winds from affecting the delta’s inhabitants while providing a sustained supply of resources.

While habitations grew on some islands, most were left undisturbed for mangroves and associated flora and fauna to thrive. A new equilibrium was reached where artisanal fishing and farming developed in tune with nature’s patterns.

Disturbed equilibrium

The equilibrium of periodic erosion and accretion that Kazi Nazrul Islam recited in his poem, and that early settlers learned to live with, is now disturbed by a combination of new anthropogenic activities. Despite strict forest protection since the 1950s and being tagged as a World Heritage Site, the Sundarbans are witnessing widespread environmental degradation from maritime transportation (for industrial raw material, fishing, and tourism), upstream dams, and a range of industrial factories in its midst.

Maritime transportation causes changes in river hydrology and creates wave wake, which increases erosion and pressures on biodiversity due to noise and water pollution. This has led to mangroves—coastal protectors, key actors in climate change mitigation, and environmental regulators—losing their ability to withstand change and its impacts.

Mangroves are known to be adaptable and resilient. These abilities helped them grow in a harsh tidal environment and adapt to salt water and frequent inundation. Mangroves in the Sundarbans found a rhythm to dance to—the balanced beats of erosion and accretion; until it was disrupted by human interventions that interfered with the sedimentation processes. Once disturbed, mangroves started losing ground. The mangrove area decreased with increasing erosion and lack of sediment settlement where new mangroves could grow.

My doctoral research showed that since 1985, the Sundarbans have lost about 137 km2 of forests due to shoreline erosion alone. Additionally, increased erosion led to changes in species composition, altered biophysical characteristics, and increased vulnerability to extreme weather impacts. Today, shoreline erosion is also the second largest cause of mangrove loss globally, following deforestation for commodities. A combination of loss of mangrove cover, ecosystem degradation, and ongoing anthropogenic impacts on sedimentation has led to a reduced protective function of mangroves in the Sundarbans.

The islands’ geography responded to this disturbed equilibrium. The 1–2 km buffer of mangroves around the islands no longer existed. Coastlines exposed to the river, like the mud-paved path I walked on, became commonplace. Houses, ponds, and farmland no longer had the protection of mangroves; they were now directly exposed to the muddy river.

“We were better off. It was only after the land loss that things turned out this way. With passing generations, we are losing prosperity. We do not have much left. We are scared that one day when we have nowhere to go, we will erode just like our motherland,” said one coastal dweller and fisher in Fokirkona, Bangladesh, back in 2021.

The mud-paved path was created, repaired, and sustained using mangrove mud by the villagers for many decades. Recently, cement, stones, and bricks replaced mangrove mud, in the name of coastal protection. But these new materials contrast with the geography of the delta. In the muddy, wet and mangrove-rich Sundarbans, they could not withstand the impact of the sea and winds or match the rhythm of the tides, and eventually collapsed.

However, as they collapsed, they caused flooding of the islands and took away farmland, ponds, front yards, and parts of or whole houses with them. The cement embankments are the new age coastal adaptations, first designed in the Netherlands, for the Netherlands’ geography. Whether or not these embankments protected the Dutch coastlines, they are now being popularly marketed and funded by international NGOs to be deployed in coastal West Bengal and Bangladesh as “climate change adaptation measures”.

Climate change adaptation is supposed to be a response that ameliorates or safeguards one from experiencing the harmful impacts of climate change. To call the cement embankments this is flawed from many angles.

First, blaming an intangible notion like climate change for the recent disequilibrium hides the impact caused by locally-induced human pressures, and creates a sense of dystopia. Second, selling ‘solutions’ that not only fail to protect shorelines, but actually increase vulnerability while decreasing the resilience of both people and nature, should be termed a ‘maladaptation’.

Living in disequilibrium

I was also curious to know why the concrete embankment, which fails to protect the shorelines and causes flooding, land loss, and transportation disruption, continues to be rebuilt. The repeated rebuilding has become the favoured measure of “coastal adaptation” for several actors. While the funding to support livelihoods and disaster risk reduction in a poverty-stricken and disaster-prone area is sorely lacking, funding for such maladaptive structures keeps flowing.

Take the case of Hemnagar, bordering India and Bangladesh along the Raimangal River, where multiple cycles of embankment construction, collapse, and reconstruction has rendered the majority of its population landless. The locals recognise the shortcomings of the embankments. However, their reliance on these maladaptive structures for sustenance is increasing.

For instance, Sheena didi, a resident of Hemnagar, has lost her house, farmland, and ponds to multiple cycles of embankments. Mangrove restoration is not a solution, as the changed ecogeomorphology of the coastline will not support mangrove plantations. Now that the current embankment is in shambles, she faces frequent flooding even in the dry season. With the next bout of embankment reconstruction, she awaits a further loss of even her small, thatched-roof shack, right next to the embankment. The locals understand the fleeting presence of these so-called ‘hard’ structures. Still, in lieu of a preparedness plan or support for one, the landless villagers have no choice but to rely on the unfulfilled promise of embankments.

One solution does not fit all

Mangrove shorelines are dynamic, and environmental stressors impact different parts of the shoreline differently based on their histories. Considering the different characteristics of the shoreline that I studied, I concluded that the adaptation to mangrove shoreline erosion needs to align with the shoreline’s geography or physical characteristics. Not addressing the root causes of mangrove shoreline erosion, the biophysical processes along the shoreline, or the socio-political aspects of shoreline protection, will result in failed adaptations and trigger a negative feedback loop that exacerbates poor resilience of the shoreline and shoreline-dwelling communities.

In the case of the Sundarbans, I realised that the coastal adaptation initially designed for the Netherlands failed to provide support and triggered a rebounding feedback loop, triggering further damage and altering the local ecogeography. Although the near future of the coastlines in the Sundarbans is uncertain, with sound mangrove restoration, management and protection, the shorelines in the Sundarbans can still be made resilient. Upon sharing my research and scoping for solutions with the local villagers in India and Bangladesh, they responded in unison: “Our Shorelines, Our Solution.”

Coastal adaptations must be customised to specificities of shorelines, including local socio-economic factors. The inhabited villages where mangroves are present should be protected, the villages where mud embankments are present should be fortified with mangrove restoration. For shorelines where embankments have been introduced, extensive support for increasing disaster preparedness and the overall resilience of the local communities should be a priority. Finally, on the uninhabited islands, mangroves should be left undisturbed and protected.

Mangroves have an inherent ability to protect coastlines, adapt to changes and mitigate climate change. With intentional, ethical, and inclusive management, the equilibrium in the Sundarbans can be restored. Such that, one day, the locals would recite Kazi’s poem, not as satire but in admiration of their local geography.

Further Reading

Bhargava, R., D. Sarkar and D. A. Friess. 2021. A cloud computing-based approach to mapping mangrove erosion and progradation: Case studies from the Sundarbans and French Guiana. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 248: 106798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2020.106798.

Bhargava, R. and D. A. Friess. 2022. Previous shoreline dynamics determine future susceptibility to cyclone impact in the Sundarban mangrove forest. Frontiers in Marine Science 9: 814577. https://doi. org/10.3389/fmars.2022.814577.

Dewan, C. 2021. Misreading the Bengal Delta: Climate change, development, and livelihoods in coastal Bangladesh. Seattle: University of Washington Press.