Photo credit: ‘White Storks in flight’ by Lawrence Hills. 2020

Hunting is a controversial topic, not only amongst conservationists but also the wider public. Our research defines hunting as the shooting or trapping of a wild animal in line with local laws and regulations. Poaching, on the other hand, is not. Nuances such as this are vital when discussing polarising conservation issues.

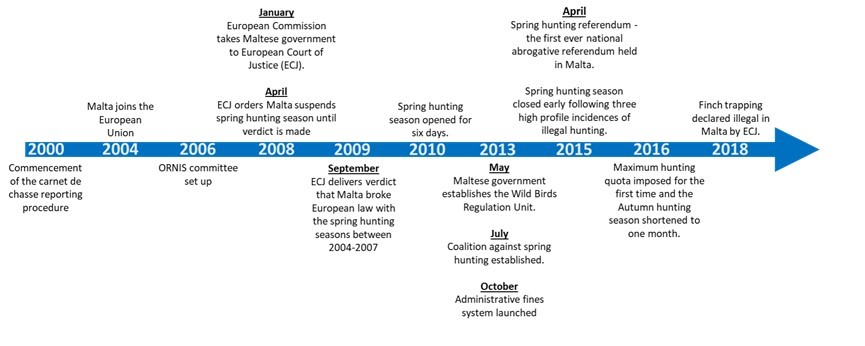

Receiving much public attention, including from the popular conservationist Chris Packham and Queen guitarist Brian May, the hunting of migratory birds in Malta is one of the high profile conservation issues in Europe. One of the smallest countries—area wise—in the world, Malta is an island nation with a rich and complex history resulting from its strategic location in the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Africa. Since entering the European Union (EU) in 2004, Malta has had to significantly adapt its national hunting laws to align with EU directives.

Being held accountable to EU directives consequently allowed international environmental NGOs, such as BirdLife Malta and Committee Against Bird Slaughter (CABS), to conduct surveillance activities and report to the European Commission. Surveillance not only monitored the breaking of hunting laws but also extended to the Maltese government, who were often accused of weak enforcement and judicial decisions that lacked severity. It is these factors that gave Malta the unenviable reputation as a “blackspot” for illegal bird hunting in the Mediterranean region.

Our research utilised multiple data sources to build a picture of how enforcement of hunting regulations, as well as trends in wildlife crime developed from 2008 to 2017. This period is important as it includes multiple key events during a time of rapid change in the landscape of bird hunting in Malta. We found that, over this period, enforcement efforts increased every year and far exceeded EU standards. Alongside enforcement, environmental NGOs also assisted with patrolling the countryside, mobilising groups of volunteers armed with cameras and drones to monitor hunters and catch poachers.

Figure 1. Key events from 2000 – 2018 surrounding bird hunting in Malta. Ferns, Campbell and Veríssimo. 2022

In what reads as good news for conservation, our research found that, alongside increasingly intense surveillance, convictions of bird-related wildlife crime reduced over this period. However, when talking to key local stakeholders—such as members of enforcement departments, a president of one of the largest hunting associations, and an experienced ornithologist—a number of contradictions emerged.

Firstly, escalating tensions among stakeholders is preventing collaborations between them. The situation is further complicated when stakeholders call into question the reliability of each other’s data, e.g. government statistics, surveillance results, and self-governance figures. Consequently, stakeholders are getting more polarised and distrust is becoming a key issue within their relationships. The distrust is so strong that it creates problems such as: poachers and hunters being considered as one and the same; physical altercations between environmental NGO members and the hunting fraternity; and the government being publicly criticised on the international stage.

Secondly, informants believe that the restrictions imposed on hunters has resulted in a worrying trend of poachers travelling to countries in North Africa and the Middle East, where governance is weaker. This is enabling greater levels of poaching than could ever be achieved in Malta. This frustration is further heightened by the reach of hunting communities through social media, rightly or wrongly, creating a sense that the limitations on home soil through EU directives only serve to increase the opportunity of hunting or poaching in other countries.

We conclude that, whilst enforcement is an important component of wildlife crime reduction, it should not always be considered as a primary tool. An unbalanced approach which neglects stakeholder engagement—in this case involvement of hunters in advocacy and governance—and traditional norms has the potential to create dynamics that are contradictory to conservation goals.

Further Reading

Ferns, B., B. Campbell and D. Veríssimo. 2022. Emerging contradictions in the enforcement of bird hunting regulations in Malta. Conservation science and practice 4(4): e12655. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.12655Veríssimo, D., and B. Campbell. 2015. Understanding stakeholder conflict between conservation and hunting in Malta. Biological Conservation 191: 812–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2015.07.018