Mithapur is a coastal town situated in Gujarat, known for the salt plant in its town more than its beaches. In fact, the place derives its name from ‘mitha’, the Gujrati word for salt. Mithapur is also referred to as the birthplace of Tata Chemicals, which took over Okha Salt works in 1939 and is today the second-largest soda ash producing company in the country.

If you happen to walk around the Mithapur and Padli villages, you cannot miss this massive factory. You will also see an open channel arising from the factory, going to the Gulf of Kutch. The channel carries industrial wastewater, including chemicals like sulphur, chlorine, and ammonium nitride. Over the years, people say that water from this channel has seeped into the ground and affected groundwater, nearby agricultural fields, and grazing lands. They also say that due to the contamination of groundwater, there are no sources of water left for them and their cattle.

Back in December 2016, when people learnt that some of these impacts could be mitigated, they filed complaints before the Gujarat Pollution Control Board (GPCB). The GPCB took note of this and issued a show-cause notice to the company after 4 months. The GPCB also directed the company to concrete over the channel along with several other directions to ensure no further seepage of wastewater into the ground. But there was no visible change in Mithapur. The people complained again to the GPCB, following which a site visit was conducted by the GPCB. Similar was given again to the company by the GPCB. There is however still no compliance, and the effluents flow through the open channel as usual.

Transferring pollution from land to sea

The people of Mithapur are now facing a dilemma. While compliance with the directions given by GPCB is being awaited, an announcement was made by the GPCB about a proposal to build a deep-sea pipeline for Tata Chemicals. An underground pipeline of 2.5 kilometres long and 45 metres wide, is proposed to be laid down, to take all the wastewater from Tata Chemicals directly into the Gulf of Kutch. The standards required for discharge onto the sea are also said to be lower as compared to inland water.

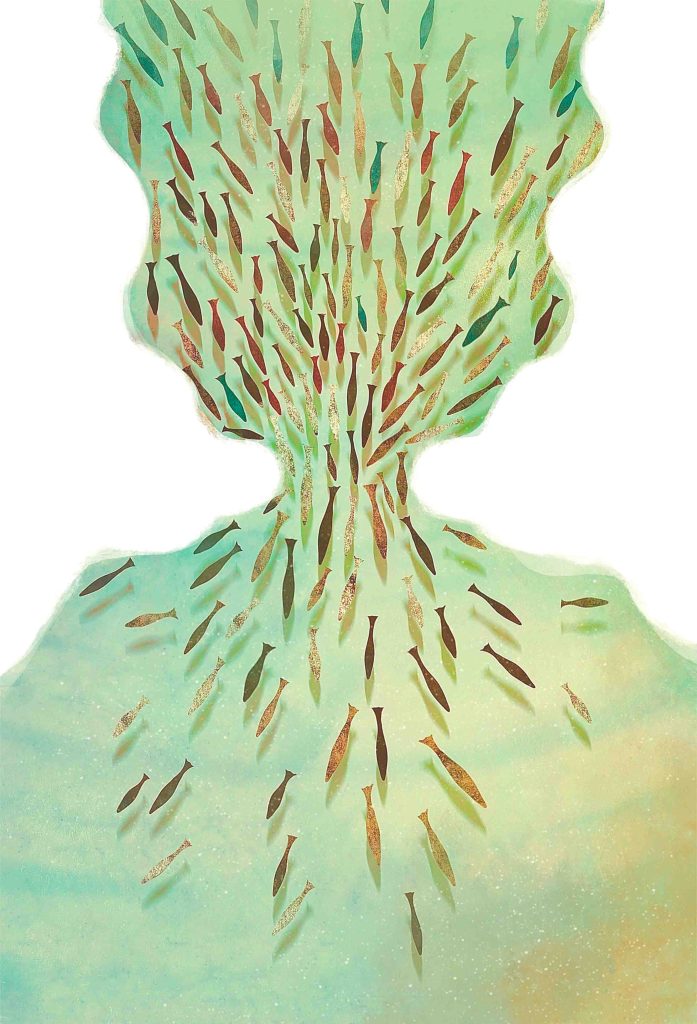

Now here is the problem. This pipeline will pass through mangroves, the Marine National Park (MNP), and will end a few meters beyond the Ecologically Sensitive Zone in the area. Established in 1982, the Gulf of Kutch MNP was the first of the 13 MNPs in India. It is home to various species of fish, corals, mangroves, octopuses and supports several marine mammals like dugongs, dolphins, and porpoises. At the same time, the Gulf of Kutch is also a source of livelihood for the fisherfolk in the area. The fishers feel that the pipeline will pose a threat to their movement since navigating in those areas will be restricted. The Environment Impact Assessment study conducted for laying the pipeline in Mithapur did not even mention the issue of access of the fisherfolk to these areas. The proposal is currently being examined by the Expert Appraisal Committee of the Environment Ministry.

Harishbhai, who is one of the complainants affected by the open channel says, “The pipeline will be a short-term solution which will solve the problem of land getting polluted, which has been happening for around 40 years now. In the longer run, it will be better to concrete the channel. The company will probably not agree to it, as they will have to stop operations for a few months. Only then can the discharge be stopped and concreting can happen.”

This story shows how governments allow for impacts to be displaced from one place to another without addressing the reasons the problem occurred in the first place. The solution of a deep-sea pipeline merely shifts the point of discharge; it does not in any way ensure better compliance by the companies or monitoring by the concerned authorities. Tata Chemicals is just one among many companies that have proposed to or laid down a deep-sea pipeline along the coastline of Gujarat. There is no publicly available information on how many such pipelines are in the pipeline in India.

A problem across the Gujarat coast

The western Indian state of Gujarat has the largest coastline in India of around 1600 km and diverse marine ecology. It has the first marine national park and sanctuary in the country that extends from the Kutch district to the Devbhumi district. This is known for its rich mangrove forests, coral reefs and is a hub for near-threatened species of birds. Gujarat also contributes to 20 percent of the nation’s fisheries production and has more than a thousand fishing villages.

The large coastline has also resulted in an influx of activities around these coastlines, making it a hub for import and export and large-scale processing units. The 1960s saw a large number of industries being set up under the Gujarat Industrial Development Act, 1962. While the Gujarat economic model has been discussed by various actors − politicians, academicians, media and the public − the pollution crisis that Gujarat has been facing has not featured in these debates.

The pollution crisis has been acknowledged over the years through various orders from the judiciary as well as academic and newspaper reports. In 2009, the Central Pollution Control Board studied the pollution levels in 88 identified industrial clusters in the country. Based on the pollution levels, 43 such clusters were identified as critically polluted areas. Six of these 43 clusters are located in Gujarat, with Vapi and Ankleshwar topping the overall list. Rivers like Amalkhadi in Ankleshwar and Khari and Sabarmati in Ahmedabad were declared unfit for domestic uses in 2012. In 2018, the MOEF&CC recognized 20 rivers in Gujarat as polluted.

History of deep-sea pipelines as a solution

We have observed that this is not the first time deep-sea pipelines were proposed to tackle land-based pollution. For example, in 2009, when Vapi was recognized as one of the most critically polluted industrial clusters in the country, an action plan was made to reduce pollution. One of the points of action was the laying of a deep-sea pipeline. Currently, treated effluents from Gujarat Industries Development Corporation(GIDC) are disposed off into the Damanganga river, impacting the livelihoods of fisherfolk.

Another instance is when in 1999, following a Gujarat high court order that disallowed releasing untreated industrial effluents into Amalkhadi river, a proposal was made to lay a deep-sea pipeline in Sarigam. The deep-sea pipeline in Sarigam however has not resulted in resolving the problem. There have been several news reports of fish mortality in these areas due to untreated effluents released into the seas. Residents have also complained that it has resulted in their health being affected. A detailed investigation of the impacts of already existing deep-sea pipelines needs to be assessed. There have also been instances of leakage in pipelines in some areas where such pipelines have been installed.

An Environmental Justice Issue: Displacing the impact

Environmental pollution problems often result in solutions where the burden is merely shifted whilst the pollution remains the same. Laying deep-sea pipelines as a response to complaints against rising pollution raises more questions than answers. What are the impacts that arise out of laying and maintaining a deep-sea pipeline? Is the pollution load being reduced or the burden being shifted?

Without having robust measures in place to ensure compliance, measures such as deep-sea pipelines will only result in displacing the pollution and shifting the impact. The shift needs to be accompanied by a structural change in how the problem of discharging untreated effluents is addressed in the first place. There needs to be more robust monitoring mechanisms and punitive measures. The basic issue of non-compliance and the impacts that arise are not dealt with. When the industries, as well as the authorities, have failed to demonstrate compliance to existing protocols, the question remains as to why there has been a shift in the dumping ground. The pipes will just become longer, but has anything else changed?