Situated off the east coast of Africa, Madagascar, the fourth largest island in the world, is a country of staggering beauty, contrasts, and unique megafauna. It has an extensive coastline of 5,000 km and as a result, substantial marine, and coastal biodiversity.

For centuries, many of Madagascar’s communities have relied on fishing for their food and livelihoods. It is estimated that at least one million Malagasy people depend directly or indirectly on fisheries for their sustenance. But an increase in unsustainable and harmful fishing practices, such as overfishing, have seen catches dwindle over the years. Fish have become scarce, and the future of many of Madagascar’s coastal communities is in peril. Its marine biodiversity is under unprecedented threat, increasingly fragile under these immense pressures, both local and external.

To address these challenges, Locally Managed Marine Areas, popularly known as LMMAs, were created in 2003 to empower coastal communities to sustainably manage Madagascar’s marine and coastal resources. These are areas of the ocean managed by coastal communities to preserve fisheries, foster marine biodiversity conservation, improve governance, and promote shared benefits. LMMAs also provide the communities with a platform for a united voice. In Madagascar, LMMAs have developed great momentum over the past 17 years, creating a contemporary community conservation movement that draws on traditional practices, shared values, and local knowledge.

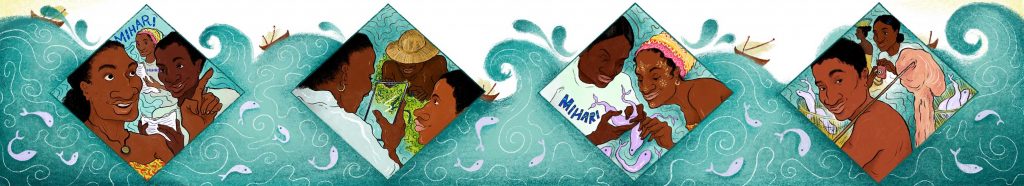

But LMMAs have faced tremendous challenges. At the centre of finding lasting solutions is Vatosoa Rakotondrazafy, a passionate Malagasy, who initially wanted to become a human rights lawyer, but found her calling fighting for the livelihoods of small-scale fishers. She is the President of the board of MIHARI, a network established in 2012 to link isolated coastal communities and allow community leaders to share ideas and successful models through peer-to-peer learning. Additionally, MIHARI was created to represent the interests of small-scale fishers at a national level, in particular fisheries policy development. Vatosoa also served as MIHARI’s first National Coordinator for six years.

MIHARI now represents over 200 LMMAs, collectively covering over 17 percent of the island’s inshore seabed.

Below is an interview with Vatosoa, where she helps to explain the challenges, threats, and opportunities, and how to create a national network of small-scale fishers.

Madagascar is the fourth largest island in the world. How important are small-scale fishers to the country’s economy and livelihoods?

Small-scale fishers are integral to coastal communities’ livelihoods and daily sustenance. In 2017, Madagascar had 163,500 tonnes of national catch, 59 percent of which was from small-scale fishers. According to the World Bank, the fishery industry is critical to our country’s economy—it contributes more than 7 percent to the national gross domestic product (GDP) and constitutes 6.6 percent of Madagascar’s total exports.

How did the LMMA movement start and grow in Madagascar?

The concept of LMMAs in Madagascar was born in the Southwest of the island in 2004, when communities came together to manage octopus closures.

Other coastal communities quickly saw the value of having LMMAs, how they could help them address their challenges, and the benefits that would come with that. Today, there are 219 LMMAs across Madagascar, covering 17,000 km2 of the country’s continental shelf. LMMAs have four types of management models or focus areas: creating temporary and permanent fisheries closures; restoring mangroves; developing alternative livelihoods; and putting in place local regulations, such as bans on destructive fishing practices.

What impact and challenges have the LMMAs had?

LMMAs have achieved a lot of success over the years. They have improved the food security and income—directly and indirectly—of over 500,000 people in Madagascar. Fisheries production has increased through no-take zones and the regulation of fishing gears. LMMAs are also critical in the conservation of marine and coastal ecosystems, including mangroves, seagrass, coral reefs, and a variety of other species. LMMA management committees support better community governance and promote community participation and decision-making in the management of marine and coastal areas.

But LMMAs have also faced challenges, such as conflicts in resource use and allocation, and a lack of a country-wide legal framework to secure and recognise small-scale fishers’ rights. Access to markets continues to be limited, and many of these LMMAs are in isolated, remote areas.

Describe the journey of creating MIHARI. Why was it necessary and what impact has it had?

MIHARI was created as a network to help address some of the challenges that LMMAs face. Today, the network has two types of members: 219 LMMA associations and 25 non-government organisations operating in the marine and coastal spaces.

MIHARI’s journey began in June 2012, when 18 LMMA associations met in southwest Madagascar and took the initiative to create a network that would promote peer-to-peer learning and give them a collective voice. I joined MIHARI in 2015 as the National Coordinator and first staff of the network. My role was to make the network more functional and to create more impact for the LMMAs. We hired more staff, created systems, and increased MIHARI membership from 50 LMMAs in 2015 to more than 200 today.

In 2020, MIHARI was recognised as an official Malagasy organisation, a huge step in cementing its legitimacy. Today, MIHARI is considered a key partner in Madagascar’s marine management and conservation efforts. It has increased the advocacy for small-scale fishers’ rights and built the capacity for LMMA leaders to be more effective. MIHARI has also created a platform that promotes learning and knowledge sharing. Increasingly, we are also focusing on promoting the human rights of small-scale fishers.

This model is also being replicated in other countries. For example, I was invited in 2018 to speak about MIHARI’s work to representatives from five countries—Japan, China, Indonesia, Thailand, and Myanmar—and provide any lessons that might be valuable for those countries as they implement their marine conservation efforts. We’re also promoting learning across the Indian Ocean and sharing valuable lessons with nearby countries.

Any advice for communities wanting to follow a similar path?

Trust traditional knowledge. Coastal communities have incredible mastery and expertise. Involve the communities in the co-creation of the networks. They are your main stakeholders and have to feel a sense of ownership.

It is critical to ensure that the government is included and supports your initiative, and ensure that you build a platform that brings all the stakeholders together to discuss the challenges and shared solutions. Ensure that you plan for exchange visits and learning so that communities can see what’s possible by observing what others have done.

I also encourage the creation of a common charter that outlines the rules of engagement so that members understand the value and benefits of the network. Lastly, there’s nothing more critical than ensuring that you communicate regularly with all your stakeholders. From communities and NGOs to the private sector and government, it’s important to keep them inspired and motivated by your work.

Can you speak about your journey in helping to lead this process? What lessons have you learned about leadership?

Leadership isn’t easy, but it is rewarding. I started leading MIHARI when I was 27. I was a young woman from the capital, leading a network that consisted mostly of men from coastal villages. I didn’t speak their local languages or understand their way of life, but I quickly learned that leadership is about how you interact with people.

I demonstrated trust and made sure that they understood that I valued their knowledge and contribution. Importantly, I made sure the communities understood that I wasn’t there to tell them what to do—I was there to work with them towards a shared vision.

You’re going through the process of developing a strategic plan for the network. What role has this played in the network’s development?

Our partner Maliasili is helping us develop our strategic plan. This has played a key role in the network’s development. A crucial step is that we’ve made the process inclusive. The strategic plan meets the objectives of the network and fits all the members.

The strategy will guide the network for the next five years and will provide clarity on our priorities. In the past, MIHARI’s work has largely been dependent on urgent needs, and we’ve been doing things on the go.

The strategic plan will give us a much-needed guide.

What do you hope MIHARI will have achieved in 20 years?

I hope that in 20 years, small-scale fishers will be playing an even bigger role in the governance of the country’s marine resources and are positioned at the forefront of creating sustainable, effective policies. My vision is to have the role of the fishers stipulated in a policy and embedded in national laws.

I also hope that the livelihoods of coastal communities are secured, that small-scale fishers have better income, and are economic actors that have the resources they need to look after marine life in Madagascar.

What are you up to now in terms of networking?

With six years of networking experience at MIHARI, mobilizing and engaging actors, I am now working with the Malagasy think tank, INDRI, whose mission is to mobilize the collective brain power of stakeholders to restore Madagascar’s terrestrial and marine landscapes. I am leading a national initiative called “Alamino”, which brings together the government, NGOs, local communities, funders, private sectors, religious leaders, researchers, civil societies, and others, to re-green the country. For the seascape, we are planning to launch the Blue Agora of Madagascar, which will allow all stakeholders in marine resources to meet, to exchange views and coordinate their action for the sustainable management of the country’s marine resources.