There are innumerable references of the mountaineering skills and the physical strength of the Sherpas who are the backbone of many expeditions which aim to scale the mighty Himalayan peaks. While the Sherpas are reputedly the strongest of mountain people, there are many others who have endured the harshness of mountain life. Vikram Singh Bisht as the name suggests was no Sherpa, but a soft-spoken and mild-mannered Garhwali. He hailed from a small pastoral village high up in the Himalayas, in a remote corner of Chamoli district in the Indian state of Uttarakhand.

Though I knew Vikram only for a month, my association with him left a lasting impression on me. I first met Vikram in May 1996 when I was on a field trip to the Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary, as a student at the Wildlife Institute of India (WII). He was then employed as a field assistant with the WII for a research project on musk deer. He had previously worked on several other WII projects in Kedarnath and had earned himself a name as one of the best field workers in this region due to his dedication and hard work. During that trip, I got hooked to the beauty and the adventure associated with the Himalayan mountains. The highlight of that trip was the sighting of a male Himalayan monal, one of the most brightly coloured birds in the world and a denizen of the high alpine slopes. That incident left me with no second thoughts, and I decided to work on the winter habitat use of the Himalayan monal in Kedaranth for my Masters dissertation. Winters in Kedarnath can be harsh, with four months of sub-zero temperatures, frost and snow. For someone like me coming from tropical southern India who had never seen snow before, it was indeed reassuring to know that Vikram was there to assist me in the field.

In the last week of November 1996, with several bundles of warm clothing, I landed in Kedarnath to commence my work on the Monal. My work was mostly concentrated around the Tungnath temple (3400 m), which is an important pilgrimage site along the southern boundary of the Kedarnath WLS. Unlike summer, when this area was frequented by pilgrims and pastoral people, hardly anyone was to be seen in winter. The pilgrimage season was over for the year and the livestock herders had also moved down to warmer areas. Vikram and I set up camp at Shokharakh (3200 m) in a log hut, which sat on a cliff edge. This was surrounded by three other cliffs and the mountain slope which led up to the Chandrashila peak (3680 m), the highest point in this range of the Himalayas. Just behind the hut, flowed a small stream which came down from the peak. Villagers from nearby areas conducted last rites for departed souls of their kin along this stream. ‘Shokharakh’ literally translated to ‘camp of silence’ in the local dialect. The campsite indeed had a spiritual air to it.

We set up camp and soon began to crisscross the entire area to study where the monal occurred. We marked several trails and paths to monitor the presence of the monal. Vikram knew the area very well – he knew the elusive musk deer bedding sites, areas the black bears were active in, and what tubers monals dug for. He could also identify trees and other vegetation. Along the trails, Vikram marked the trees with a red paint and where necessary he would tie a red ribbon; these would be the only indication of the trail when the area was completely snowbound. Over the weeks Vikram and I worked closely to run the camp and do the fieldwork, for we were the only two people around. Vikram’s days were often longer than mine since he also attended to the bulk of camp duties. Most of our conversations revolved around his wild encounters, the mountain spirits, his village, his family and kids, but would invariably end with discussions about snowfall in the area. Our initial weeks at Shokharakh were a fight against time since there was heavy snow in the last week of December. Thereafter, regular snowfall occurred until the middle of April and the whole area would be covered with three to four feet of snow.

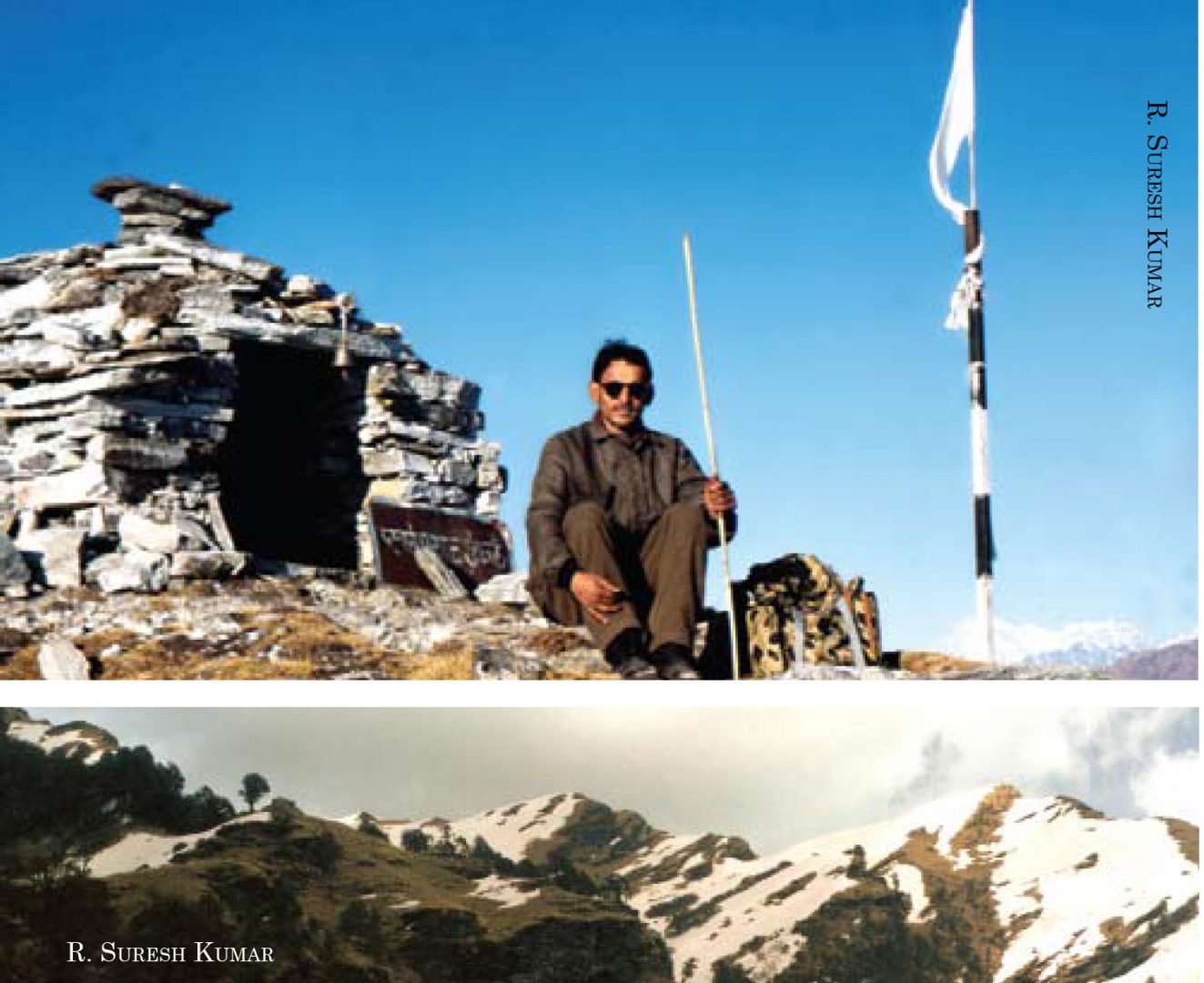

The last week of December had come and gone, and the weather appeared to be favourable with no signs of heavy snowfall in the near future. Taking advantage of this situation, Vikram and I decided to trek to the Chandrashila peak on the first day of the year 1997. En route to the peak, we stopped at the Tungnath temple and offered prayers. On my persuasion, Vikram had decided to give up his beedies as a New Year resolution. Soon we were atop the peak and the breathtaking panoramic view of the snow-clad peaks to the north left us spellbound. As a token of respect to the mountain, we made a cairn of few small stones there. Delighted at our small achievement, we quickly took pictures of each other and trekked back to camp.

The next few days were routine – we marked more trails and searched for signs of the monal. On the morning of January 4, I found that Vikram had woken up very early and was sitting in the kitchen staring at the fire in the hearth. I noticed a strange uneasy look on his face as if something was worrying him deeply. Upon enquiring what the matter was, he replied in an agitated tone that he would have to go home immediately and do some prayers and offerings as he was getting nightmares in the camp. Though I was surprised by his sudden outburst, I calmed him down and decided to move down to a lower camp, so Vikram could go home for a few days.

Later, on the way to the lower camp, we marked one last trail that was left to be completed. At one point along the trail where pilgrims regularly offered prayers to a set of stones neatly arranged on the ground, Vikram prayed for a long time. He removed the fallen leaves from there and painted the “om” sign on the rocks. He truly seemed worried. Later on the same day, he left for home, while I stayed behind in the lower camp.

A week passed but there was no sign of Vikram returning or the much-awaited snowfall. The next day a boy in his teens, Prem Singh, arrived at camp saying he was Vikram’s brother. He had been sent by his brother saying he was worried that I would be having problems without anyone to assist me with my work. Prem told me that Vikram would be joining us soon after completing his prayers. On the night of January 19, the first snowfall began – overnight the entire area was transformed. I was all excited about the snow but deep down I was worried about Vikram’s absence. Two days later when there was a break in the snowfall, two strangers arrived at the camp late in the evening. The men appeared physically exhausted after having to plough through fresh snow for nearly five km to get to our camp. They had come to take Prem Singh along since Vikram was seriously ill, and wanted to return to their village the same evening though it was dark. Shocked by the news, I too decided to go down to the village and visit the hospital in the nearby town where he was admitted.

The next day, I found Vikram in an emaciated state at the government hospital. He had become unbelievably thin and it was hard to recognise him. He had lost his speech, his movement and I learnt that he was unable to recognise anyone. His listless eyes stared straight at the hospital ceiling. I learnt from his mother who was there that he worried a lot about me and had fainted a few days earlier while he was preparing to leave for our camp. I again visited Vikram the next day. While I sat holding his motionless hands, consoling him that he will be fine soon, a tear trickled down the side of his cheek. He had recognised me! With great difficulty, I went back to the campsite. It was very difficult to find someone to assist me since everyone in the village believed that Vikram was attacked by a mountain spirit, but at last, I managed to find another person. Vikram passed away on January 27 at the hospital; the reason remains a mystery.

The following months during fieldwork, I sensed Vikram’s presence around me all the time. The slippery parts of the trail where he would put out his hand to help me, the pile of stones atop the Chandrashila peak, the vantage points atop the cliffs where we would sit together and look for monal, and missed the hot rotis that he would serve. He had become an integral part of my life and it was very hard to accept that he would never return. Many years have passed since I met Vikram, and the paint marks that he left on the trees and rocks have faded away, but I can never forget the enthusiasm for fieldwork and the thoughtfulness and caring nature of this simple mountain man. Even today the view of the mountains, its snow-covered peaks and the distant ringing call of the monal, instantly brings back vivid memories of Vikram Singh Bisht.