On a late sunny afternoon back in April 2019, I was talking to Shamsudheen, or Shamsu bhai as we call him. We were standing outside the Dak Bungalow on Minicoy, an island in the Lakshadweep archipelago off the coast of Kerala, India. Shamsu bhai is the President of Maliku Masveringe Jamaath—a traditional body that decides the rules and practices for managing Minicoy’s pole and line tuna fishery. Being the island from where the pole and line tuna fishery was transferred to other Lakshadweep Islands, I was seeking to document Minicoy’s traditional fisheries management systems.

After a not-so-successful field trip in March, I was back on the island looking for potential interviewees. Shamsudheen, being busy with official duties, was suggesting the names of other knowledgeable fishers on the island. That’s when Mohammed Kalumangothi, fondly known on the island as Kalumaan, appeared on his black Yamaha RX100. Sitting on his motorbike, wearing a broad smile, he asked Shamsu bhai what was happening. In response, Shamsu bhai looked at me and said, “Here’s the answer to all your questions.” And that was the first time that I, Abel, met Kalumaan.

Kalumaan, a knowledgeable fisherman and the lone communist on the island, has an interesting personality. He started fishing when he was 14, and now in his early 50s, he already has decades of fishing experience. Being the skillful and likeable person that he is, he has been one of the most popular kelus (boat captains) in Minicoy. Padmini, Agartala, Bahrain, Kamyaab are just some of the many boats that Kalumaan has captained across the 11 villages on the island.

Each year during the month of Ramadan, after the Eshah prayer in the evening, the island that is still and calm during the day comes to life. People go shopping, and are seen conversing over tea by the beach or taking walks, while some women are busy preparing special Ramadan delicacies. And this is when our work begins as well.

Post dinner at Hotel Aboo & Sons each night, I take an auto rickshaw and head to Kalumaan’s place. As I near Falessery village, in the distance, I always see Kalumaan eagerly waiting for me. He then takes me to his wife’s house where he resides at night as per Minicoy’s matrilocal system. “Baa aadyam chaaya kudikkaam,” he says and serves me kattan chaaya (black tea) along with bodu appam and riha appam, Minicoy’s favourite evening snacks.

On our way to the seashore, where Kalumaan loves to spend his evenings, he opens his chellam (a tiny box) and takes out a few karambus (cloves) to chew on. At the sandy beach, under the starry sky, he spreads a cloth for us to sit on. Boats with blinking red lights on top are anchored close to shore. Crabs are milling around, and the cool sea breeze carries a fishy, salty scent.

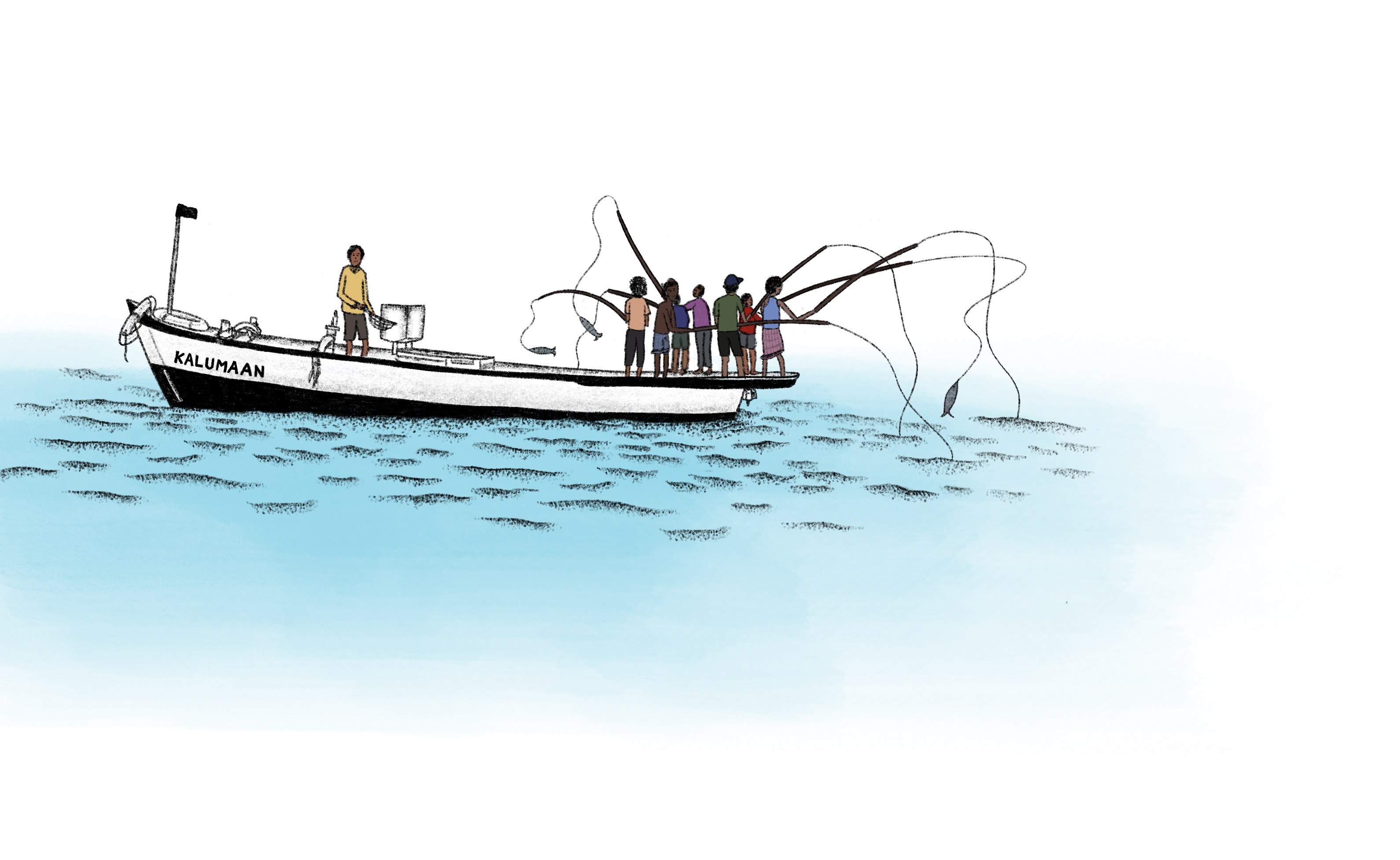

“Enthoru haramaanu?” He asks if this much fun can be experienced anywhere on the mainland. Only once the above routine is completed is Kalumaan ready to answer questions about Chaala and Choora. Baitfish, locally known as Chaala, is one of the critical factors for Lakshadweep’s pole and line tuna fishing. Pole and line is a sustainable fishing method owing to its selective, non-invasive, and small-scale approach. This technique has its origin in the Maldives from where it spread to Minicoy. A comprehensive system of traditional fisheries management that covers the spatial and temporal aspects of resource management has evolved in Minicoy over time. However, while transferring pole and line from Minicoy to the other Lakshadweep islands in the 1960s, these systems were left behind.

Kalumaan’s in-depth knowledge about every species he interacts with during his fishing ventures is remarkable. Whether it’s baitfish or coral ecology, or the behaviour of turtles, sting rays and octopuses or the catching techniques of vembolu, metti or chammelli, Kalumaan knows it all. From the 2019 field season alone, we have over 8.5 hours of recorded interviews with him. And this was excluding the countless informal monologues of his that were packed with useful information. It was Kalumaan, with his enthusiasm and cheerfulness, who made the strenuous documentation exercise engaging for us. Our ongoing work attempts to document this knowledge so that other similar coastal systems can also learn from Minicoy’s traditional resource management systems. Having said that, this knowledge is also key to Minicoy’s existence, as the island is heavily dependent on natural resources and its systems are vulnerable to unsustainable transitions.

Kalumaan’s wisdom is not restricted to individual species or their ecosystems, but extends to the ocean at large. Sea salinity, current patterns, fishing grounds, underwater terrain, navigation based on the Nakaiy calendar (an indigenous Maldivian calendar system) and astronomical knowledge—these are some of the many aspects he is well-versed in. All of this is knowledge he has gathered through observation over the years. “Suppose we already caught a thousand tuna, and another boat is trying to catch from the same school the easy way, without using a single baitfish, which is against the Jamaath’s norm, then, dip a steel glass in the water and all the tuna will flee, leaving nothing for anyone to fish.”

It isn’t only his technical know-how or skills that make Kalumaan unique. He motivated two men with disabilities to join his fishing crew when nobody else was keen on taking them on. An old colleague of ours, having merely transcribed the recorded interviews of Kalumaan, was intrigued by his compassionate tales and engaging conversations. Keen on meeting him, she made it to Minicoy in the next field season, and made friends with Kalumaan. He is also a local celebrity. Young boys on motorbikes, men lounging in beach shacks and women carrying headloads of filleted tuna to village kitchens all greet him as “sakhave” (comrade) or “Kalumaan kaaka” as they pass. “Allah! What can I say, it’s full of acquaintances here, that’s the problem,” Kalumaan turns to us and says with a grin on his face.

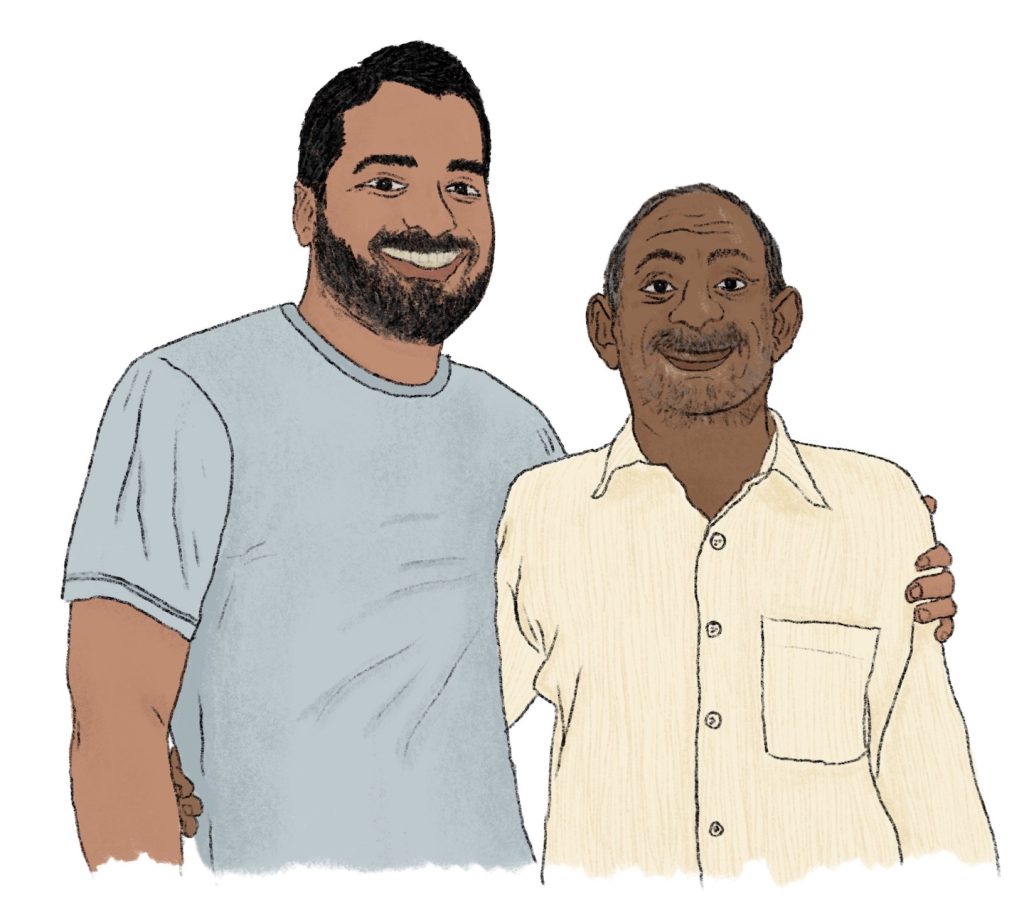

Fast forward to March 2023, I am still in awe of the hospitality, warmth and trust that he extends to us. Even Diya, who was carrying out fieldwork on the island for the first time and a total stranger to Kalumaan, was received with a tour of his entire village and an invitation to attend a family wedding. Always welcoming, never averse to being asked questions—what more can a researcher ask from someone in the community that they work with? It is people like Kalumaan who make our work possible on the island. And that comes with the responsibility to not feel entitled to all the support we have been given.

Although he always appears jovial, Kalumaan has faced his fair share of hardships. Over the past two decades, he has lost three boats—two to cyclones and one during peak monsoon in 2004, while rescuing the crew onboard MT Indira after their engine failed. To date, he hasn’t received any compensation for the boats he lost, even after filing several applications. But that never stopped him from lending a hand to those in need. A migrant worker we met recently at the Minicoy jetty, was telling us how Kalumaan helped all of them who were stranded on the island during the COVID-19 lockdown by giving them fish for free and making sure they all had a decent meal every day. At times, Kalumaan also gives money to a person with a mental illness so that he doesn’t have to go hungry. And in his unique fashion, Kalumaan invited the entire island, including non-islanders, to his daughter’s wedding by posting an invitation on the local television channel!

Kalumaan hasn’t changed in the few years that we have known him, but things have changed for him. The man who spent most of his life at sea is now seen only on the shore, having become paralysed along his right side at the beginning of 2022. He was airlifted to the mainland, where he underwent surgery and prolonged treatment. He is now back on the islands almost a year later but continues to be on medication and physiotherapy. Still, just yesterday before writing this account, we were there once again sitting on the shore with Kalumaan, laughing at his hilarious accounts of crabs having tussles with rats, and listening to his revolutionary ideas about replacing diesel power generators with wave energy projects so that the daylong power cuts on the island due to diesel shortages can be a thing of the past.

¹ Samundar ka guru means the guru of the sea in Hindi. We came across some Hindi-speaking seamen in Minicoy referring to Kalumaan as such during our fieldwork on the island earlier this year.

Further Reading

Abraham, A. J. and A. Sridhar. 2021. Plural islands of Lakshadweep: Insider-outsider narratives of Minicoy. Le thinnai Revi. https://medium.com/thinnairevi/pluralislands-of-lakshadweep-insider-outsider-narratives ofminicoy-by-abel-job-abraham-and-de8b03715fd. Accessed on April 20, 2023.

Khot, I., M. Khan, P. Gawde, A. J. Abraham, A. Raj, R. Sen and N. Namboothri. 2023. Fish for the Future: Creating participatory and sustainable fisheries governance pathways in the Lakshadweep Islands — A 10-year report. Bengaluru: Dakshin Foundation.

Namboothri N., I. Khot and A. J. Abraham. 2022. Small islands, big lessons: Critical insights into sustainable fisheries from India’s coral atolls. In: Conservation through sustainable use: Lessons from India. (eds. Varghese A., M. A. Oommen, M. M. Paul and S. Nath). 1st edition. Pp. 27–40. London: Routledge India. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003343493