Turtle walker extraordinaire – Rom Whitaker

In the early 1970s, the Madras Snake Park, located very close to the Indian Institute of Technology, was a magnet for a certain breed of student who just couldn’t bear the drudgery of a college education. Since I was of the same non-academic ilk, I encouraged them to hang out with us and help develop the Snake Park’s field activities of conservation and research. One of these stalwarts was Satish Bhaskar, a quietly intense young man from IIT, whose passion was jogging several kilometres each morning to Elliot’s Beach to have a swim in the ocean.

We had recently started nocturnal beach walks to find olive ridley sea turtle nests before the poachers got them and rebury them in a safe hatchery we had set up at the Cholamandal Artists Colony. Satish got into this routine with zest and his strength was a welcome addition when we had to carry heavy bags of eggs back to the hatchery. The rest of us at the Snake Park were hung up on snakes and crocodiles and it was Satish’s dedicated single-mindedness that made me suggest to him that India needs a Mr. Sea Turtle and he would be the ideal man for the job.

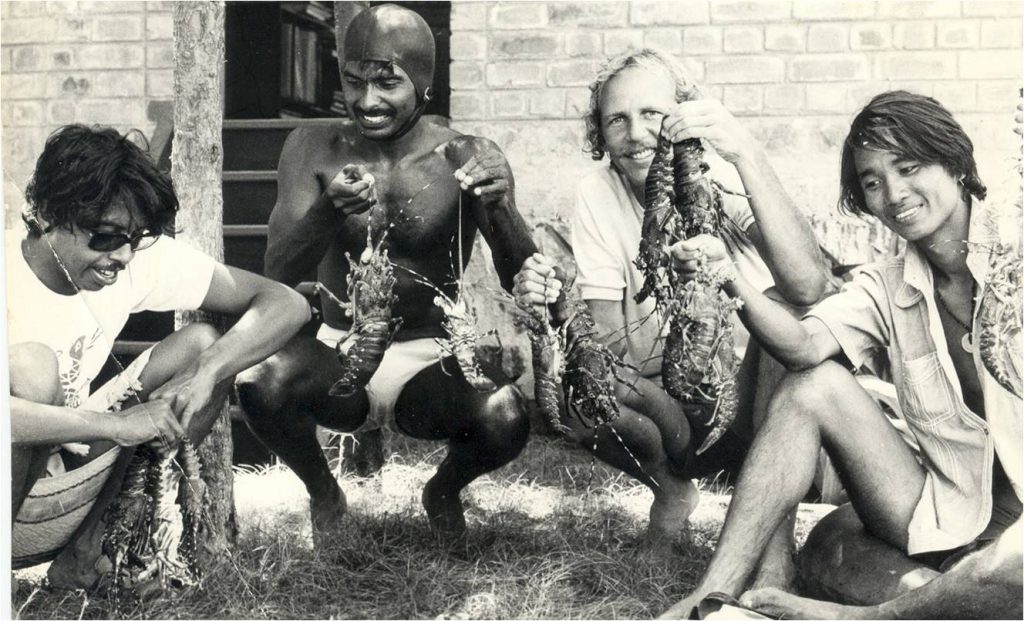

He obviously took this idea to heart and, starting with the meagre resources the Snake Park provided him, he began his sea turtle surveys. His intrepid trips covering both the beaches of mainland India and eventually the Lakshadweep, Andaman and Nicobar Islands were made possible by the World Wildlife Fund and other donors, and resulted in close to 50 reports, notes and papers. But it was his entertaining letters that grabbed us the most. Writing from the Nicobar Islands, he described the torture of sand flies during the day and by mosquitoes at night. One night on a remote Nicobar beach, he bedded down on the mat with mosquito net stitched to it (an invention we made). Very early next morning, he was awakened by a shuffling sound and he opened one eye to watch a saltwater crocodile walk past him and slide into the surf ten metres away. Surveying those beaches, he had to swim across frequent small estuaries, always keeping an eye out for crocodiles. In a remarkable nine-month trip in 1979, he covered almost all the islands in the archipelago and then returned several times in the 1980s to visit the others.

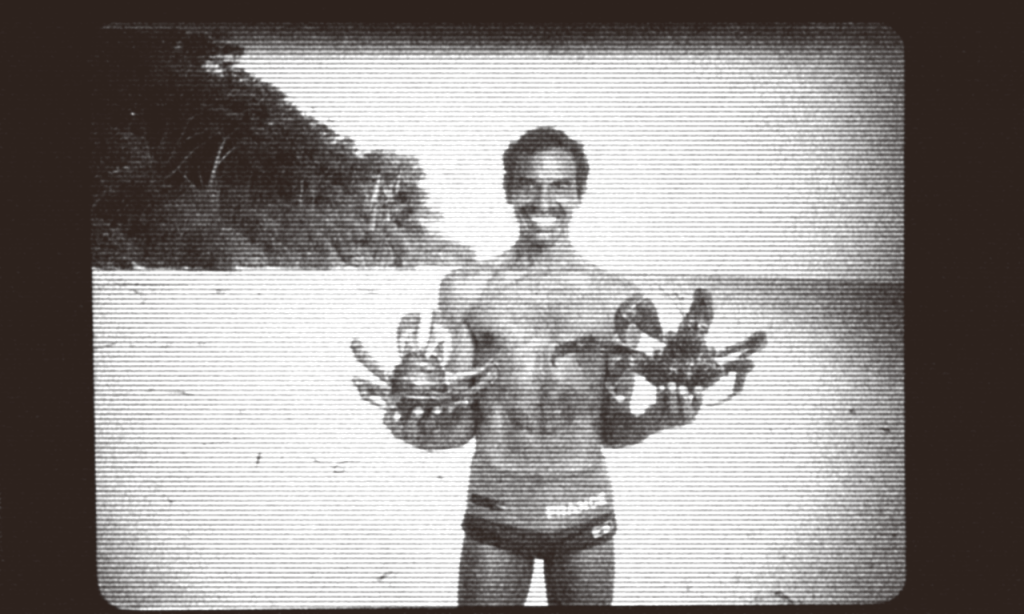

After his first trip to the Lakshadweep in 1977, he told us that he would love to stay and study the green sea turtle nesting beach on Suhelipara, one of the uninhabited islands. He said the only problem was that they nested during the monsoon and there was no boat traffic then as the seas were too rough. “I’ll have to maroon myself on the island for the whole monsoon,” he said with a smile. We started going over all the things that could go wrong, anything from a bad toothache to malaria or an upset tummy could put a real damper on this idea, but he was adamant and did maroon himself on the island between June and September 1982. Famously, his letter in a bottle floated to Sri Lanka and reached his wife just 24 days after he had thrown it into the surf at the edge of the lagoon. The boat that was due to pick him was just one month late!! But not much fazed Satish in the field.

Satish really kick-started interest in sea turtle conservation in India and I’m proud that I had a role in it.

Being inspired by the turtle man – Kartik Shanker

When I met Satish in the late 1980s, he had just returned from his surveys in West Papua, Indonesia, that WWF had supported. The beaches were remote and accessible only by a boat that passed once in a few weeks. He was the first outsider that the Papuans in Wermon had ever met, and he communicated with the world by swimming out to said boat and giving them letters to post. He counted over 13,000 leatherback nests and tagged 700 turtles almost single-handedly. Over the next decade, the leatherback populations declined and the locals decided that Satish was the cause—that he had tagged the turtles with metal tags so he could steal them later with a giant magnet.

In Chennai, we had just started the turtle walks through the Students’ Sea Turtle Conservation Network. As youngsters, we were all in awe of all the things that he had done, which of course we heard about from Rom Whitaker, Harry Andrews and others. Satish was too self-effacing to tell the stories, other than in a completely matter-of-fact way. His knowledge of sea turtles was vast and his attention to detail was exceptional, but his generosity outdid all of that. He shared his knowledge and his collection of papers and slides freely with us, including the first edition of Biology and Conservation of Sea Turtles, a collection of articles that emerged from the first ever global conference on sea turtles that was a bible for many years for the community. Satish’s article in the collection is the first comprehensive account of sea turtle nesting across India.

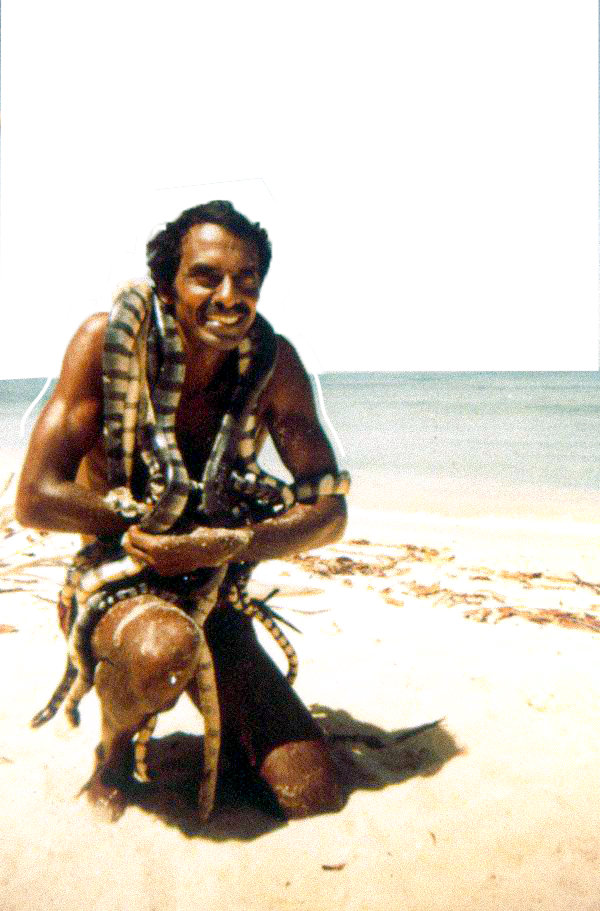

A few years later, Satish returned to the islands to survey Great Nicobar Island along with Manjula Tiwari and then decided to initiate a monitoring programme for hawksbill turtles on South Reef Island. He would camp out on this tiny island (just 700m long and a little over 100m wide) with his assistant Saw Emway and swim to Interview Island to get water. On one of those trips, they were chased by one of Interview’s feral elephants, and Satish threw his shirt off to distract it. He later retrieved the shredded shirt and posted it to his wife, Brenda.

In the early 1990s, Satish and Brenda, on a whim, decided to move to Goa, and he had little contact with his colleagues for several years afterwards. Aaron Lobo, an eager 12-yearold naturalist, happened to meet Satish in Benaulim, Goa, by complete chance. Satish’s children studied French with Aaron’s aunt, whom he would visit. From then on, he started visiting Satish regularly and they wandered about on the beaches and the scrub around Satish’s house, looking for snakes and other critters.

After completing his Masters at the Wildlife Institute of India, Aaron talked to Satish about an upcoming trip to the Gulf of Mannar to document sea snakes in the region. Since Satish had conducted his first field survey there, he decided to accompany Aaron and spend a few months with him. There were many interesting experiences and sightings, but most eventfully, they were at sea on a trawler on 24 December 2004, when the tsunami struck. Fortunately, the wave passed safely under their boat while they were sleeping. During this time, they travelled together to several parts of the Gulf of Mannar coast, snorkelling in the shallows. Over two decades earlier, Satish had seen giant spider conches numbering in their hundreds, but they had dwindled to just a few. During the night, they combed the beaches for sea kraits—sea snakes that came ashore to lay their eggs and digest their prey. Satish had encountered these frequently in the Andaman islands, but Aaron never found any in the Gulf of Mannar.

The rest of us had little contact with Satish in the intervening years. In 2010, we conducted the International Sea Turtle Society’s Annual Symposium in Goa. We honoured Satish with the Sea Turtle Champion’s Award. Though the who’s who of the global community were present, Satish declined to collect the award and I had to deliver it to him at home. But he did sneak into town to meet his old Karen friends who were attending the conference.

In 2018, filmmaker Taira Malaney and her team decided to make a film on Satish’s life. When we heard that they had convinced him to return to ANET and South Reef Island, the turtle fanatics Muralidharan, Adhith Swaminathan and I decided that we would just have to go along. We landed in Mayabunder and Satish had a touching reunion with Saw Uncle Paung, who had accompanied him on many of his early surveys.

A friendly forest officer offered to take Satish back to South Reef once he heard about Satish’s seminal surveys there. After a long boat ride, we reached Interview Island, where to our considerable surprise, we found Saw Emway, who had been Satish’s field assistant in the 1990s. We proceeded to South Reef Island, but the boat could no longer land there due to changes in topography after the tsunami. Satish, who until then had looked like the 72-year old he was, threw off his clothes, donned his fins, slipped into the water and started swimming to the island. Emway, the film crew and I quickly followed suit. On the island, Satish was rejuvenated as he walked around the island remembering where hawksbills had nested when he was there two decades earlier.

I’ve spent the last 25 years studying sea turtles across India. Everywhere I’ve been, from the Andaman and Nicobar Islands to Lakshadweep to Papua, Satish has been there before and left his mark. It’s easy to get obsessed with sea turtles, but even easier when you’ve had Satish Bhaskar as your mentor and inspiration. After recurring bouts of ill health, Brenda passed away in October 2022 and Satish a few months later in March 2023. He is survived by his children, Nyla, Kyle, and Sandhya.

There are many, many more Satish stories. Read about his adventures here:

https://www.seaturtlesofindia.org/talking-turtles/satish-bhaskar/

https://www.iotn.org/iotn12-07-special-profile-satish-bhaskar/