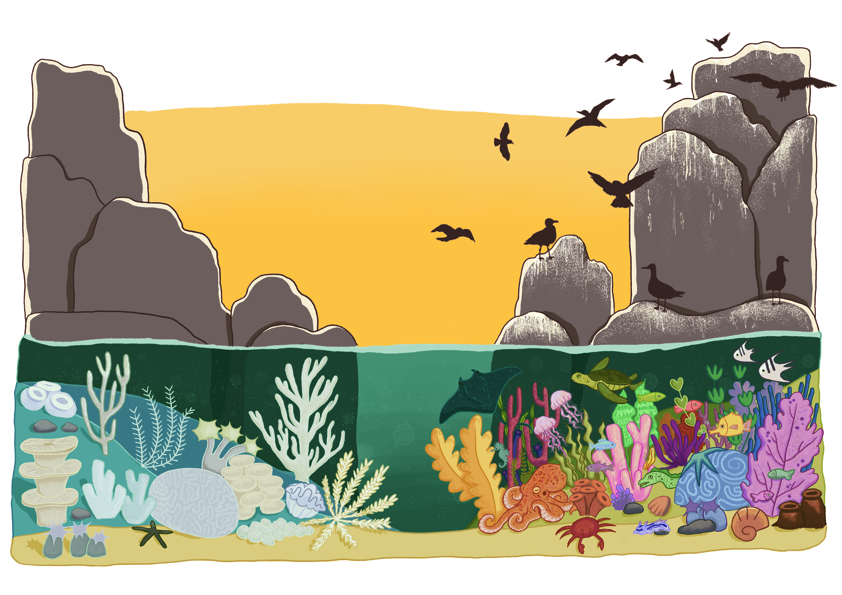

As a source of guano (or bird poop)—a highly sought after agricultural fertiliser—seabird nesting sites have economic benefits. But beyond this, seabird poop also serves an ecological function, as a source of nutrients for corals. A recent paper published in Science Advances shows how seabird colonies, via the bird poop deposited there, can enable coral reefs to cope with climate change

In this study, researchers delved into the complex relationship between seabirds and coral reefs. Their findings revealed that seabird guano dramatically increases productivity in coral reefs. At the same time, it makes reefs more resilient to climate change.

Fantastic seabirds and where the authors found them

The study, led by Dr. Cassandra Benkwitt, a Senior Research Fellow at Lancaster Environment Centre, was conducted in Chagos, a group of 60 islands in the Indian Ocean. Over an electronic interview, she explained, “We have previously observed seabirds increasing fish biomass and growth rates. This led us to examine their potential role in coral reef recovery following marine heatwaves.”

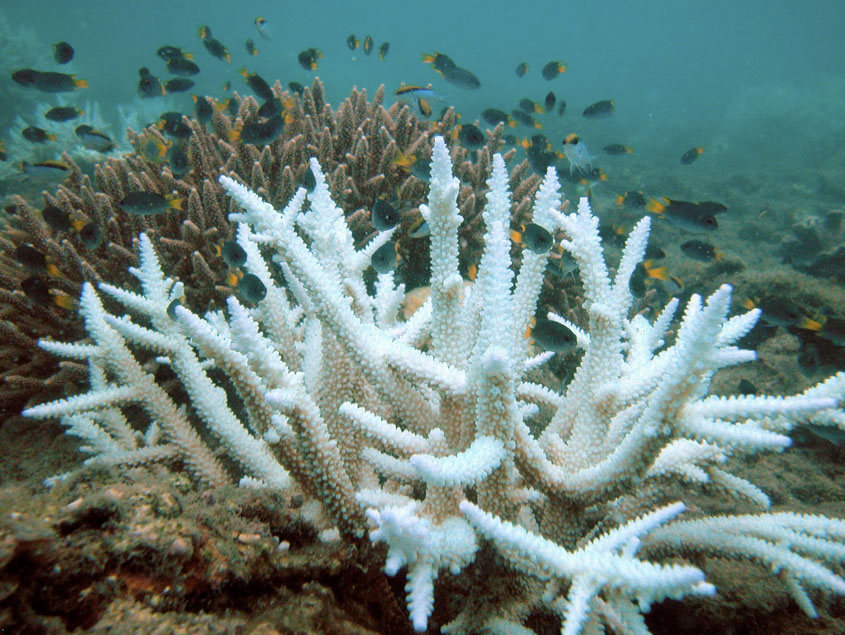

Seabird poop, rich in nitrogen and phosphorus, is a natural fertilizer for coral reefs. Benkwitt noted that lab-based studies suggested, “certain nutrients might benefit corals against heat stress”. Field experiments revealed that reefs near the islands with thriving seabird colonies experienced twice the coral growth compared to reefs with fewer seabirds. The team also transplanted corals from areas with fewer to more abundant seabird populations. Within three years, the corals fully acclimatized and thrived in the high nutrient conditions. However, when they transplanted corals from areas with abundant seabirds to those with fewer, the results indicated a drop in growth rate.

Global shifts, local tricks

Seabirds, even in the islands of Chagos, are declining in numbers—primarily due to invasive alien species such as rats, bycatch in fisheries and climate change. The study sheds light on the impacts of this decline. Nutrient inputs to reefs were low in areas where seabird populations had decreased, with a similar reduction in coral growth. This, in turn, increased the chances of coral bleaching and disease.

This research highlights the importance of understanding the complex relationships within ecosystems, stressing the need to conserve seabirds to protect coral reefs. According to Benkwitt, only by protecting and restoring seabird populations will the nutrient cycle be restored. Thus, by protecting seemingly unconnected species, we can strengthen the resilience of entire ecosystems. Looking ahead, Benkwitt plans to track the fate of reefs over extended periods.

“Tackling global climate change is certainly a top priority,” stated Benkwitt, “but it is a huge undertaking, and progress has been slow.” She suggests looking into local remedies to support ecosystems. “We need easier, shorter-term, local solutions. These can help buy coral reefs time. Meanwhile, we continue addressing global issues.”

Our lands and seas are connected. Degradation of one can affect the other. This study emphasises the importance of ecosystem connectivity and why restoring natural connections should be part of conservation efforts. By taking advantage of these services provided by seabirds, we can work towards a better future for coral reefs and the countless species that depend on them.

Further Reading:

Benkwitt, C. E., C. D’Angelo, R. E. Dunn, R. L. Gunn, S. Healing, M. L. Mardones, J. Wiedenmann et al. 2023. Seabirds boost coral reef resilience. Science Advances 9(49): eadj0390. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adj0390.