It is April 2023, and we are making our way across Laikipia in central Kenya. We travel down a public dirt road that cuts through a large, private wildlife conservancy. The road is lined by an electric fence on either side. Beyond the fence lies 58,000 acres of enclosed habitat for endangered and endemic species, including black rhinos, Grévy’s zebra and wild dog. This conservancy also contains its own wildlife rescue centre, which offers sanctuary to some unexpected animals, including a pygmy hippo, a spotted owl and even a bear.

This part of Laikipia has been hit hard by successive years of drought. Although the rains have finally arrived elsewhere in the region, evidence of rain in these parts is scant. As we drive, large plumes of dust are propelled high into the sky. Behind the electric fences on either side of us, there are just a few tufts of grass and some common, hardy plants remaining, such as buffalo thorn (Ziziphus mucronata) and whistling thorn (Vachellia drepanolobium).

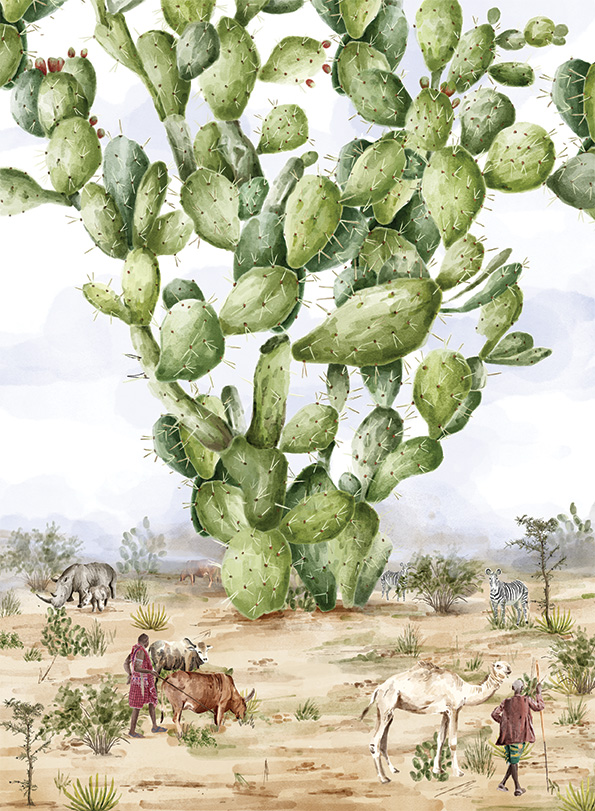

We are driving to Waso Centre in west Laikipia, passing through community-owned lands that make up the larger Naibunga Community Conservancy on the way. The fence of the private conservancy ends and a sudden and stark difference in ground cover makes the boundary between the private conservancy and the community-owned land clear. On the community side, the ground is almost entirely bare aside from cacti and succulents. As we drive on, more and more of the earth is covered by one distinct plant: Opuntia or prickly pear. The flat, oval stems of this cactus—loaded with long, needle-like spines—can be seen for miles, reaching up towards the sky out of the dusty soil.

Although impossible to know for certain, it is widely agreed that various species of Opuntia were imported to Kenya from South America by white settlers in the 1950s. Some say the plant was first brought to Kenya by a colonial homesteader in Dol Dol—just 12 kilometres from where we are driving to now. It was apparently kept as an ornamental potted plant that could survive in arid environments. Others report that colonial administrators used the cactus to construct living fences around their office buildings.

Some of the Opuntia species introduced to the region have since died off, but Opuntia stricta has thrived on community land. This species requires very little water to grow, which has allowed it to spread with relative ease. In 2018, the United States Forest Service was contracted to carry out a study on the spread of Opuntia in Naibunga Community Conservancy, which revealed that the species is present on 90 percent of the conservancy’s landscape and completely dominates vegetation on 12 percent of the land.

As Opuntia spreads, it displaces and suppresses grasses vital for livestock and wildlife. In the absence of other options, animals graze on the prickly pears produced by the plants. The reddish-purple fruits pose grave injury to cattle, goats and sheep. The cactus spines lacerate the mouths of foraging livestock and can become lodged in their eyes, leading to blindness. Livestock also have trouble digesting the seeds of the fruit, which may clog the intestines of goats and sheep, leaving them unable to feed and ultimately causing their demise.

In places like Naibunga, where livestock keeping is people’s main source of livelihood, this ecological legacy of colonisation has become a persistent thorn in the flesh of pastoralists and is of growing concern for some types of wildlife as the plant continues to reproduce and spread. Many across the conservancy are attempting to take action, removing the plant and replacing it with indigenous grasses and shrubs, but Opuntia is difficult to control. As we carry on towards Waso, we pass through areas where local residents and civil society organisations have been attempting to carry out this work. The plant has been dug up and left in large mounds on the side of the road. In some areas, potholes have been filled with the uprooted remains of the plants. In some ways, these extreme efforts are a symbolic testament to the durability of prickly pears as a species and the ecological legacy of colonisation.

Paradoxically, use of Opuntia as a pothole filler has contributed to the plant’s spread. As vehicles pass over the flowers, fruits and stems, pieces of cactus penetrate tyres, hitching a ride across the landscape, propagating across the arid landscape and spreading further. Most scholarship on settler colonialism draws attention to how settler colonial power endures through political institutions, land use policies and legislation. These forces and processes are all undeniably essential to sustaining settler colonialism. Yet, settler colonialism is also memorialised and lives on through ecological relations. As the story of Opuntia so aptly illustrates, the ecological relations produced through settler colonialism can continue to violently suppress, remove and erase indigenous lives—including human, animal and plant lives—well after formal independence, just as other structural forces may.

All over the world, evidence of colonialism is detectable in the ecologies of post-colonies long after the official start of independence and end of empire. As Lenzner et al., 2022, write, “the persistent legacy of human activities on biological invasions over centuries reflected in the compositional similarity and homogenisation of their floras”. It was also intended that settler colonialism would impact on and endure through ecologies, including relationships between humans, animals and plants. The mid-20th Century writings of Elspeth Huxley, a white settler to Kenya, reflect the following sentiment:

“It is sometimes said that if Europeans were to withdraw from Africa today the continent and its people would revert to savagery and all traces of our civilisation would be expunged. This is not altogether true. Whatever the fate of our cultural influence, we should at least leave behind indelible traces of our cattle and sheep in the hereditary mechanism of animals which survived us. We should leave plants that have colonised the soil perhaps more permanently than men – wheat and barley, sisal and coffee, oats and tea, potatoes and peas, fruit and wattle trees. These at least would remain as a memorial to Europe’s conquest of Africa.” (Huxley, 1953)

Ecological imprinting is neither just an accident nor by product of settler colonialism, but has always been part of the mandate of colonisers. The 2020s have proven to be a crucial decade for biodiversity, following the IUCN World Conservation Congress in Marseille, France, and the adoption of the Kunming Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF). A total of 188 governments signed onto the GBF, agreeing to coordinate and escalate efforts to halt and reverse the ongoing loss of marine and terrestrial biodiversity. With these commitments, massive amounts of funding are being made available to support the implementation of the GBF. The story of Opuntia in Laikipia, Kenya, is just one example of many that underscore the need to continue dismantling unjust ecological legacies of settler colonialism. Using GBF funding to directly support efforts to redress historical ecological injustices is therefore not only possible but essential for restoring and safeguarding healthier ecosystems for all people, animals and forms of life.

Further Reading

Bersaglio, B. and C. Enns. 2024. Settler ecologies and the future of biodiversity: Insights from Laikipia, Kenya. Conservation and Society 22(1): 1–13.

Braverman, I. 2023. Settling nature: The conservation regime in Palestine-Israel. University of Minnesota Press.

Enns, C. and B. Bersaglio. 2024. Settler Ecologies: The Enduring Nature of Settler Colonialism in Kenya. University of Toronto Press.