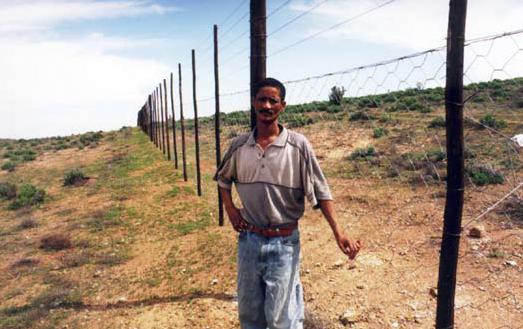

It has now been nearly five years since Mac Chapin’s article, ‘A Challenge to conservationists’ (2004) caused a stir that reverberated through the 2004 World Conservation Congress (WCC) in Bangkok. Although many readers will be familiar with Chapin’s article, which provoked the largest outpouring of reader letters ever received by World Watch, his main points are worth reiterating here. First, Chapin noted that a growing portion of the money available globally for biodiversity conservation increasingly is being controlled by the three largest conservation NGOs: the Nature Conservancy, Conservation International, and the World Wide Fund for Nature. Dowie (2009) has added the Wildlife Conservation Society and the African Wildlife Foundation. Next, he pointed out that the growth of these organizations coincided with a general failure of conservation practice. Finally, he expressed concern over the growing influence of the World Bank, bilateral agencies and corporations on conservation NGOs. He argued that this situation made it increasingly difficult for conservation big NGOs (BINGOs) to be critical of the environmentally and socially disruptive spread of corporate enterprise, extractive industries. Many of Chapin’s observations and arguments have been echoed in the work of journalist Mark Dowie, which culminated this year in the publication of Conservation Refugees (2009).

This special issue of Current Conservation is the product of a network of scholars, activists, and conservation practitioners who have also observed and documented the kinds of dynamics noted by Chapin and Dowie. Members of this network also share observations that there has been a clear move beyond simple partnership between corporate interests and global conservation, to an apparent paradigm shift in which economic growth and big business increasingly are presented as essential to successful biodiversity conservation and a sustainable future for our planet.

In other words, there appears to be a strengthening consensus that there is a synergistic relationship between growing markets and the protection of nature. This consensus, which can be seen in both the realms of concept and practice, is variously referred to as market environmentalism (Anderson and Leal 1991), green neoliberalism (Goldman 2005), green capitalism (Heartfield 2008) and neoliberal conservation (Igoe and Brockington 2006; Sullivan 2006).

We are aware that these terms are widely, and to a certain extent justifiably, regarded as opaque jargon by many who work in the realm of international conservation. In this collection, therefore, we strive to be as clear as we what we are talking about. An excellent possibly can about the particulars of place to begin is Bram Buscher’s (2008) concise and thorough treatment of what the ‘neoliberalisation’ of conservation looks like in a specific intellectual/policy context. His case study of the 2007 meetings of the Society for Conservation Biology (SCB) describes the alignment of conservation with market forces, seen through the pervasiveness of certain ideas and rhetoric. He was especially concerned with assertions that markets can bring about win-win solutions through conservation interventions, in which value is added to nature through ecotourism and ‘ecosystem services.’ Most recently the concept of ‘cultural services’ has been added to this discussion.

This increasingly pervasive and powerful narrative about markets and nature asserts that value added to nature through various kinds of for-profit investment and finance can provide incentives for local people to protect nature, and thus also enjoy a profit from the ‘cultural services’ that they provide in protecting global biodiversity. It will also provide the financial means necessary to protect the gains made in the global expansion of protected areas during the 1990s in a context where parks are being rapidly downsized and degazetted. This thinking was pervasive at the most recent WCC in Barcelona.

The entrance to the Congress was aesthetically dominated by corporate displays, while the Congress featured films with titles such as ‘Conservation is Everybody’s Business’. The Congress was also marked by contentious struggles over an emerging partnership between the IUCN and the Rio Tinto Mining Group, as well as another between the IUCN and Shell Oil. Research by Ken MacDonald (forthcoming) and Saul Cohen (forthcoming) on the Congress reveals how specific groups within the IUCN used various kinds of marketing and performance to make market-based conservation appear unproblematically compatible with social justice and ecological sustainability.

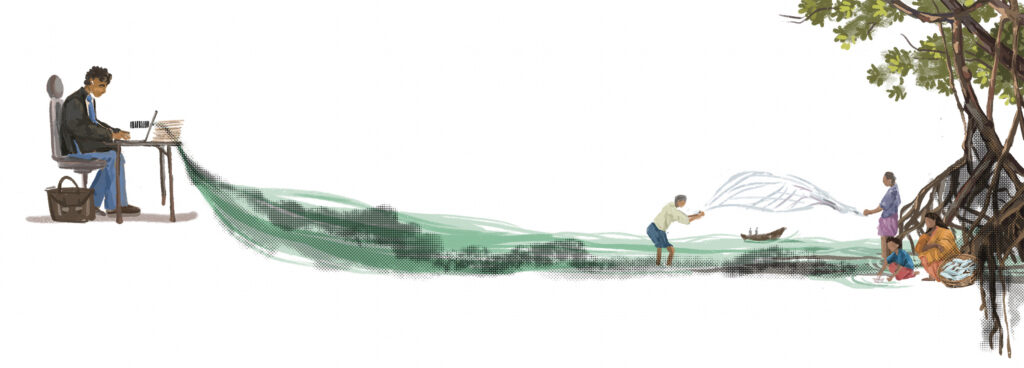

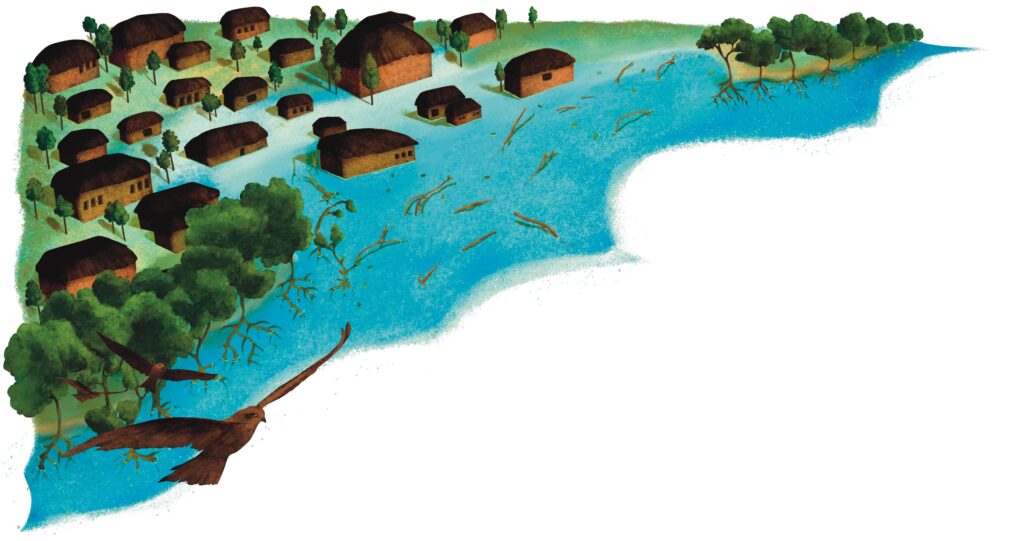

We find these transformations concerning on a number of levels. As work by Zoe Young (2002) and Michael Goldman(2005) have shown, the greening of the WorldBank and the creation of the Global Environment Facility (GEF) in the 1990s facilitated the extension of market logic into natural and cultural realms previously beyond its reach. This process has revolved around the phenomenon that social scientists from Marx on refer to as commodification, the transformation of objects and processes into products and experiences accruing monetary value determined by trading in frequently distant markets (Castree 2007; Brockington et al. 2008). Thus spectacular landscapes are transformed to become high-end tourist destinations, often at the expense of local people and their livelihoods (West and Carrier 2004).3 Thus a rainforest is reconceptualised as a specified number of carbon credits or the environmental damage of a gold mine is calculated in ways that make it appear amenable to offsetting by nature protection in another context. The underlying logic is that the higher the price for a tradable commodity species, a landscape, a cultural practice, or an ‘ecosystem service’ the more likely it becomes that the commodity will be conserved or sustainably utilised into the future.

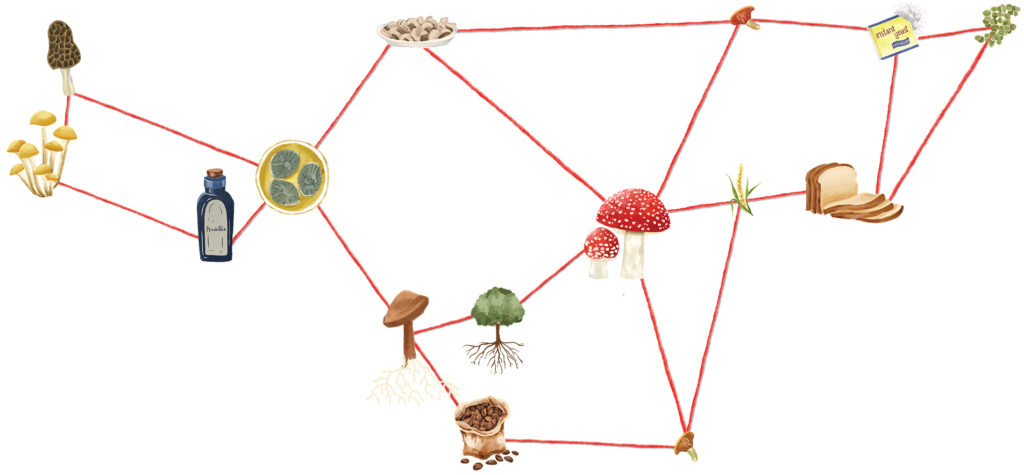

An economistic application of the term ‘ecosystem services’ (as posited by Costanza et al. 1987 and the Millenium Ecosystem Assessment (2005) thus reduces and transforms complex natural and social phenomena into pricedand thereby tradable commodities whose priced value is set from afar (Sullivan 2009a and 2009b). An especially problematic aspect of these processes of commodification is that of environmental and social mitigation.

Basically, this proposes the substitutability of one landscape for another, an environmental good for an environmental bad, and market opportunities of the livelihood practices and lifeworlds of people living on the landscapes in question. These concepts increasingly are deployed in association with extractive enterprises such as hydroelectric dams (Goldman 2005) and oil pipelines (Brockington et al. 2008), which harm the environment and contribute to the physical, social, and economic displacement of local people. The mitigation concept proposes that these types of harm can be corrected through nature conservation in other landscapes, combined with the absorption of displaced people into market-based economic opportunities. You can see how mitigation is presented in terms of business opportunity at the website of the Business and Biodiversity Offsets Program.

Conservation and capitalism are thus transforming the world in partnership (Brockington et al.2008). Conservation grows with extractive enterprise and large scale development. It grows through promoting a global tourist industry that is heavily dependent on ecologically and economically unsustainable fossil fuel consumption (Chapin 2004; Carrier and MacLeod 2005; Sullivan 2006; Neves forthcoming). It grows through the promotion of consumer goods such as green credit cards, Starbuck’s conservation coffee, and McDonalds Endangered Animal Happy Meals (Igoe, Neves and Brockington forthcoming). Finally, it grows alongside extractive enterprise through the provision of mitigating services and carbon offsets. In other words, conservation grows as capitalism matures and spreads, and vice versa. According to these arguments, biodiversity conservation and ecological sustainability appear to be best achieved through increased consumption.

Countering this logic is difficult. As a general rule, the analyses presented in this special issue have not been well received in conservation circles. As Buscher (2007: 230) has argued, the types of win-win scenarios proposed by neoliberal conservation are highly effective in bringing together ‘a broad variety of interests and goals into apparently immutable objectives that can be embraced by all’. It thus is especially valuable in mobilising resources and support for conservation NGOs and interventions, which increasingly are also opportunities for business investment. In his systematic observations of the 2007 SCB meetings, Buscher noted that presentations of these kinds of ideas and scenarios more often were cast in terms of consensus-building than in terms of ‘intellectually sound and clear argumentation’. He thus concludes that the promotion of these types of concepts and scenarios tautologically affirms the very market logic they are promoting, a phenomenon he calls ‘market science.’ In market science ‘the best knowledge is apparently that which the most knowledge consumers (i.e., the audience) buy into’. From a scientific stand point, Buscher concludes, this is a problematic state of affairs. He acknowledges the urgency of biodiversity conservation, and the corresponding need to build constituencies and procure financial support/investment. At the same time, he warns that doing this without an empirically grounded understanding of the often problematic complexities of relationships between global markets, ‘the environment’, and local peoples and livelihoods can contribute to the perpetuation of social injustice, as well as to paradoxically undermining the goals of biodiversity conservation. Despite the difficulties of bringing alternative views into the arena of conservation business, we think these developments require critical analysis and challenge. The links between capitalism and conservation are more problematic than mainstream ideas regarding synergistic relationships between markets and the environment

would have us believe. In some cases global conservation may be facilitating processes and relationships that undermine its own goals of protecting the environment and creating sustainability. In others, market-based approaches to conservation often are inimical to both good conservation and democratic processes.

Nevertheless, we also caution against treating conservation, and particularly conservation NGOs, as a group that acts in concert and always in agreement. It is true that many of the practices described above and their associated rhetoric are present in conservation NGOs: with so many of these organisations receiving various forms of support from the World Bank and bilateral development organisations, this is hardly surprising (cf. Young 2002). But it also is interesting to note the diversity of responses to these global pressures and funding flows that are visible in the conservation NGO sector. Despite an emphasis on consensus building, and the common stance that large global conservation meetings appear to encourage, it is intriguing to observe the variety of practice engaged in by different NGOs in their respective contexts of action. The empirically grounded studies of conservation performance and policy which this network has collated, some of which are reported below, thus describe considerable variety in policies, practices and consequences. Different NGOs working in the same region can behave in very different ways. Indeed the same NGO’s performance in different regions also can vary considerably. These are structures and institutions which themselves produce diversity (see especially Dowie 2009).

This diversity in the conservation movement is reflected by the fact that some of the authors of the articles in this special issue themselves were working for conservation NGOs when they formed their views, and all have worked closely with them. This collection itself was reviewed and critiqued by other members and former members and employees of conservation NGOs. In other words, this is not a sector which can be easily typecast.

Unfortunately, it also has been a frequent common experience that the formal institutional responses to our work have not been sympathetic. In some cases our work and writing has been actively shut down and shut out through censorship, threats and proposed legal action. It has seemed at times that the knowledge we have produced through research and reflection somehow is ‘disobedient’ and subject to disciplining as such, which is why we use the term ‘disobedient knowledge’ here. Clearly, the knowledge we have produced in collaboration with local people and situated in local contexts does not mesh well with the ideas and rhetoric of neoliberal conservation. Nevertheless we remain convinced that it is relevant, in terms of both conservation and social justice agendas. Because of our concerns we have been working together to create an alternative locus of knowledge production concerning biodiversity conservation, sustainability, and our collective future. Based on our experiences we are working to design this locus of knowledge with the following principles in mind:

1) Collaboration: Current approaches to conservation, especially market-oriented ones, are driven by competition. NGOs compete with one another for sources of conservation funding. At the same time, scholars researching and producing knowledge regarding conservation, frequently in close collaboration with local people, also compete with each other for even scarcer sources of research funding, often provided by NGOs or the foundations that fund them;

2) Affinity and Common Concern: Research on conservation issues often is built around the availability of certain sources of funding, which may be tied to particular perspectives and agendas. We are attempting to build a research network that is minimally influenced by funding priorities, emphasising instead collaboration, friendship and shared concerns for both biological and cultural diversity;

3) Inductive and Empirical Research, Open to Scrutiny and Contestation: Our goal is to weave theories and discussions regarding conservation and sustainability that emerge from a diversity of empirical observations from different parts of the world. We are building these perspectives from patterns that we have noticed arising from our observations in many different locales and contexts. Our goal is to present these perspectives in both web-based forums that are interactive in nature creating opportunity for dialogue and debate, as well as to publish in journals and other outlets, of which we intend this issue of Current Conservation as an initial collaborative contribution; and finally

4) Openness: Collaborative knowledge building depends on modes of communication that are, as far as possible, open, sincere, and constructive. In a competitive environment geared towards funding and profit, there are strong incentives to communicate in ways that cast doubt on perspectives and information that may be seen as undermining the procurement of funding and institutional growth. Such modes of communication often require the overlooking of perspectives and information that might be essential for effective institutional learning. We do not envision this alternative locus of knowledge production to be standing in opposition to, or even wholly separate from, mainstream conservation. Our intention is rather that it will contribute to new types of productive tensions that broaden our understanding of conservation and its problematic relationships to capitalism, consumerism, and institutional competition.

Our hope is that the conversations emerging from these productive tensions will reveal that alternatives to market-oriented conservation deserve more substantial consideration in policy circles, academic research, and public understandings of environmental issues. A full discussion of such alternatives is beyond the scope of this special issue. We anticipate that these will be the topic of upcoming conversations. We look forward to being part of these, as well as working with similarly committed people to imagine and implement alternative futures.

References:

Brockington, D., R. Duffy, and J. Igoe.2008. Nature Unbound: Conservation, Capitalism, and the Future of Protected Areas. London: Earthscan.

Büscher, B. 2008. Conservation, Neoliberalism and Social Science: A Critical Reflection on the SCB 2007 Annual Meeting, South Africa. Conservation Biology 22(2): 229-231.

Chapin, M. 2004. A Challenge to Conservationists. World Watch November/December: 17-31. Cohen, S. Forthcoming. How to NASDAQ the Environment: the Science and Performance of Neoliberal Conservation at the World Conservation Congress.

Dowie, M. 2009. Conservation Refugees: the 100 Year Conflict Between Global Conservation and Native People. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Goldman, M. 2005. Imperial Nature: The World Bank and Struggles for Social Justice in the Age of Globalization. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Carrier, J. and D. Macleod. 2005. Bursting the Bubble: the Socio-Cultural Context of Ecotourism. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 11: 315-334.

Castree, N. 2007. Neoliberalizing Nature: The Logics of De- and Re- Regulation. Environment and Planning A4: 131-152.

Costanza, R., R. d’Arge, S. de Groot, M. Farber, B. Grasso, K. Hannon, S. Limburg, R. Naeem, J. O’Neill, R. Paruelo, R. Raskin, P. Sutton and M. van den Belt. 1987. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387: 253-260.

MacDonald, K. Forthcoming. Business, Biodiversity and New ‘Fields’ of Conservation. Conservation and Society.

MEA. 2005. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment: Ecosystems and Human Well-being. Washington DC: Island Press.

Neves, K. Forthcoming. Cashing in on Ecotourism: A Critical Ecological Engagement with Dominant E-NGO Discourses on Whaling, Cetacean

Conservation, and Whale Watching. Antipodes.

Sullivan, S. 2006. The elephant in the room? Problematizing ‘new’ (neoliberal) biodiversity conservation. Forum for Development Studies 33(1): 105-135.

Sullivan, S. 2009a. An Ecosystem at Your Service: Environmental Strategists are Redefining Nature as a Capitalist Commodity. The Land Winter 2008/2009.

Sullivan, S. 2009b. Green Capitalism and the Cultural Poverty of Constructing Nature as Service Provider. Radical Anthropology 3: 18-27.

Terry L.A. and D.R. Leal. 1991. Free- Market Environmentalism. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

West, P. and J. Carrier. 2004. Getting Away from it all? Ecotourism and Authenticity. Current Anthropology 45(4): 483-498.

Young, Z. 2002. A New Green Order?The World Bank and the Politics of the Global Environment Facility. London: Pluto Press.