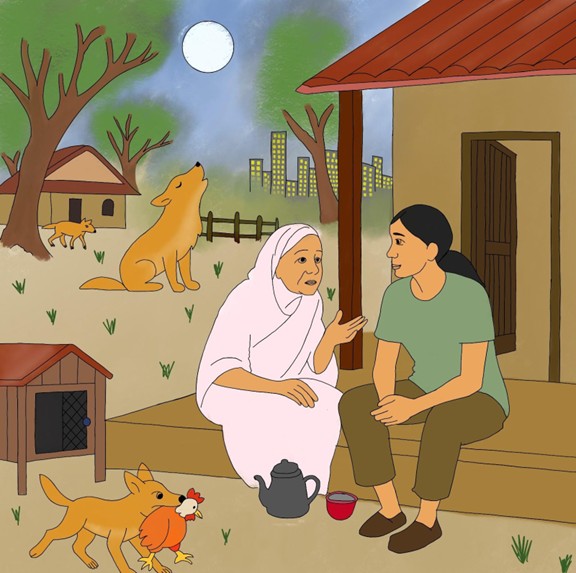

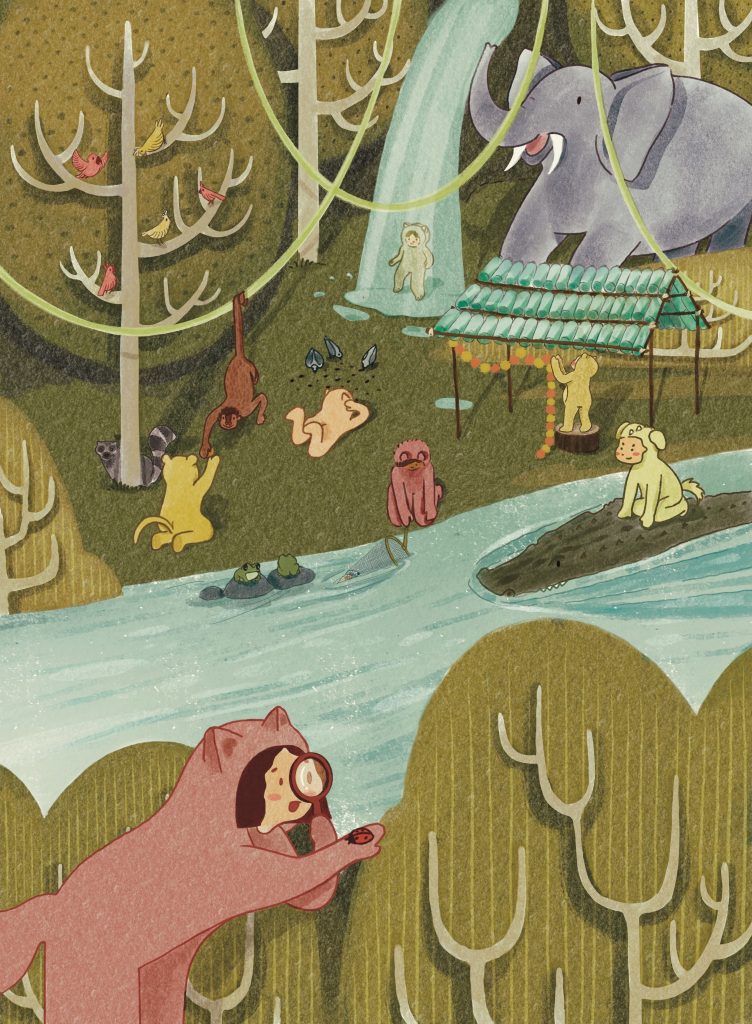

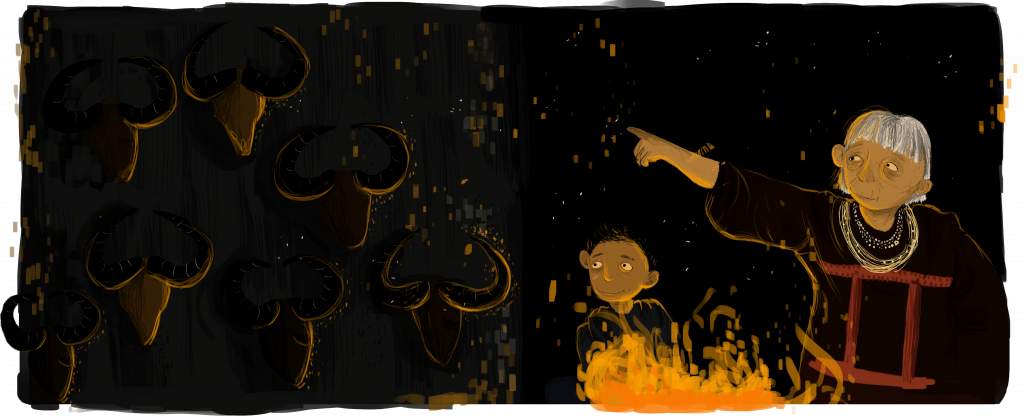

It was Jeeha Tacho’s favourite time of the day. All was quiet in the tiny village of Etabe, where he lived. The family had finished the work for the day, and he sat with his grandmother by the fire. “Naya, what story will you tell me tonight?”

Jeeha loved Naya’s stories. Naya’s stories were the stories of his people, the Idu Mishmi, passed down from generations. Jeeha’s favourite stories were about the animals that lived in the forests and the mountains that surrounded his tiny village.

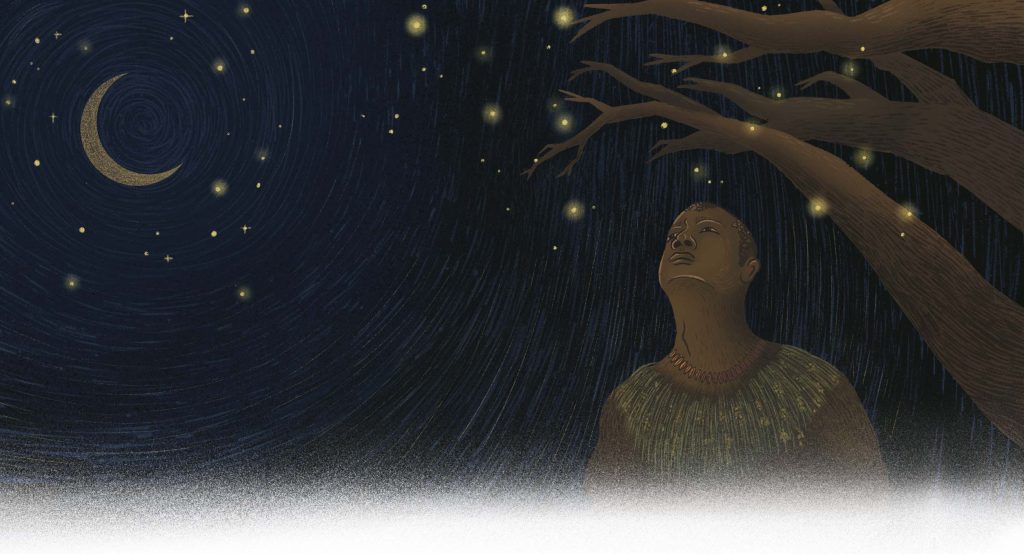

Naya’s face glowed in the reflection of the fire. “Let me think. Today, I will tell you about the ākrū.” she said.

“What is the ākrū, Naya?”

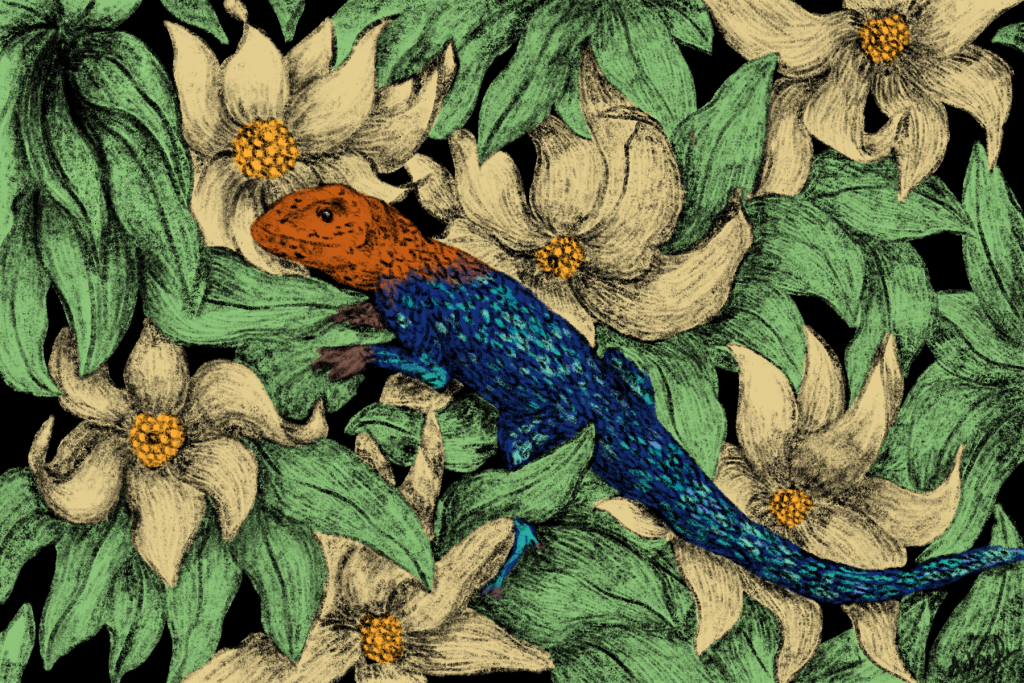

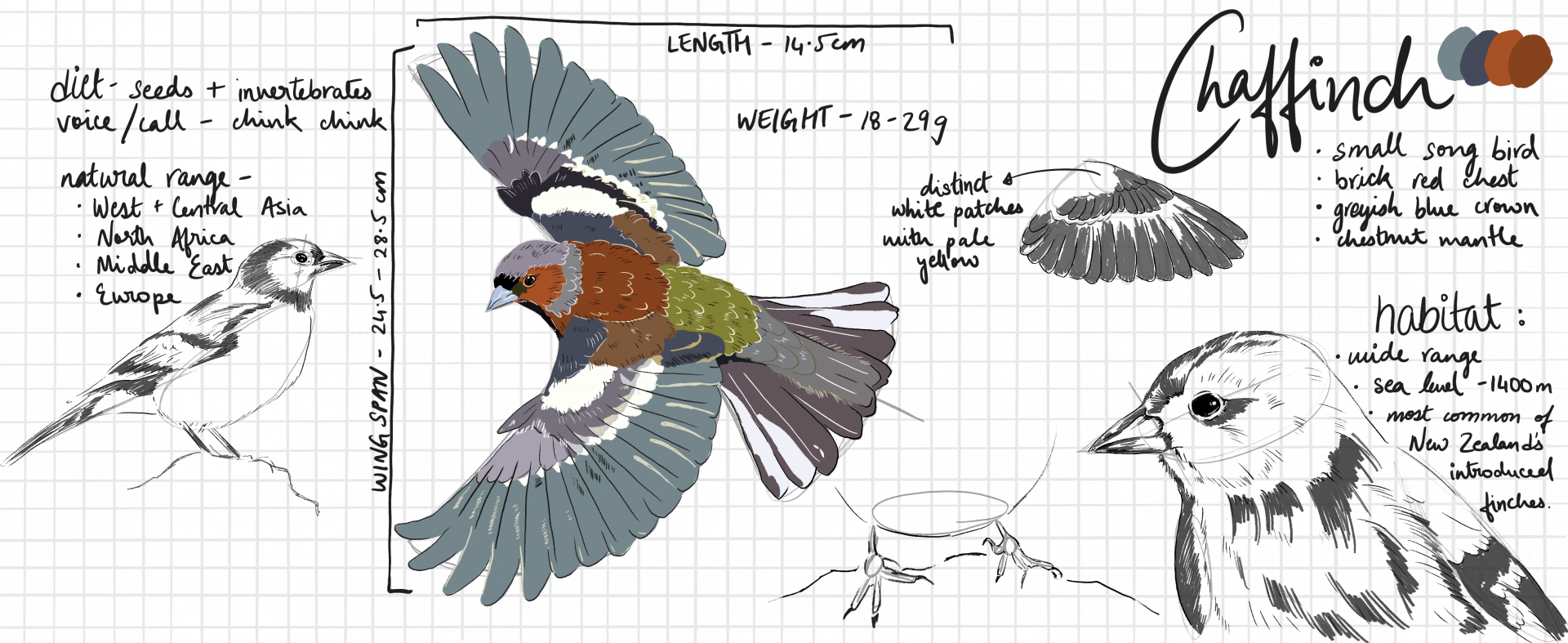

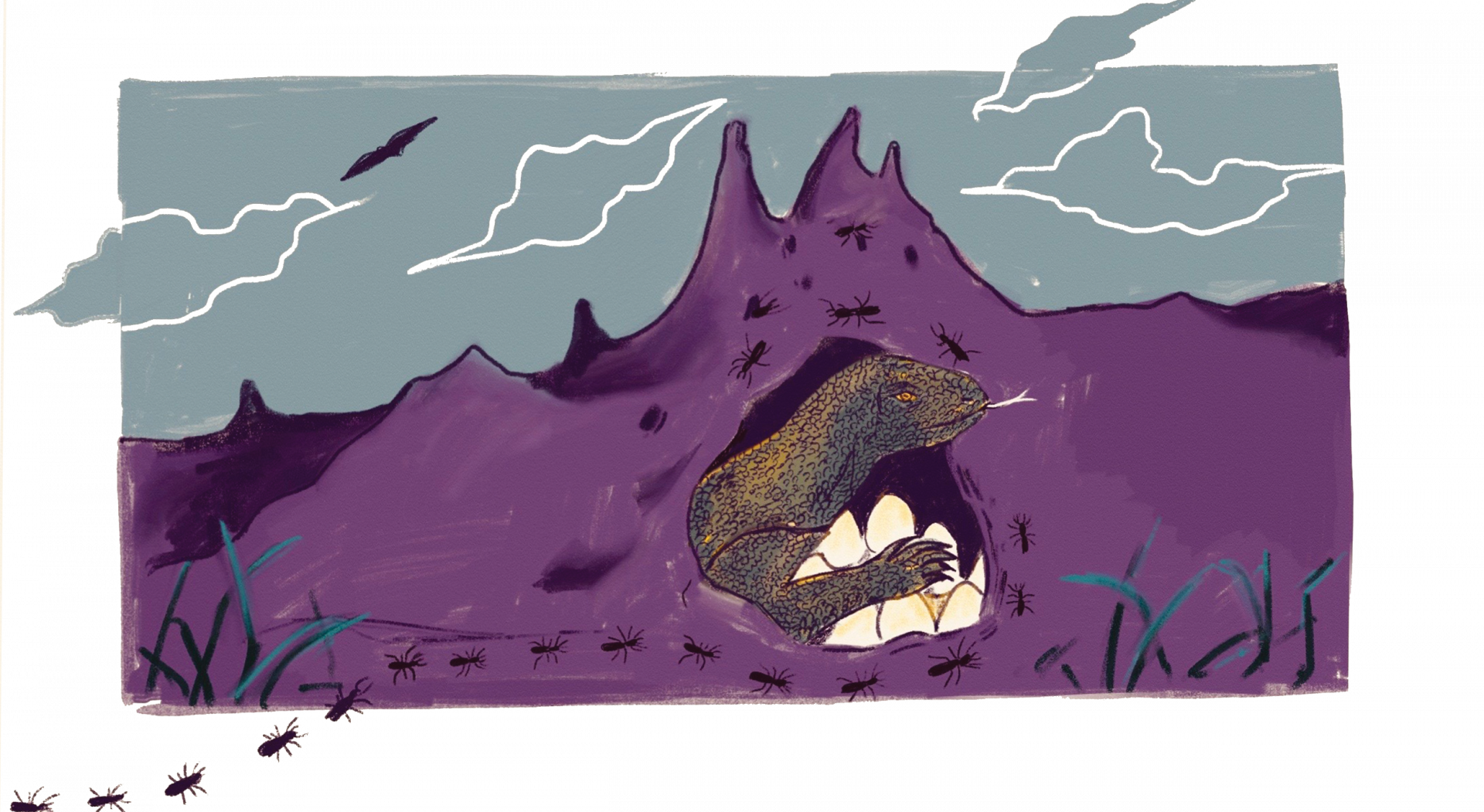

“The ākrū lives in the high mountains. It is a strange-looking animal, like a mix of a goat and an antelope. It has a heavy, hairy body, and hunched shoulders with a thick short neck. But it has short legs and a short tail. What makes it look even odder is its nose, which looks like a swollen black bulb.”

Little Jeeha closed his eyes and painted a visual picture of the ākrū as Naya described it. “Does it have horns, Naya? Like the màcō (sambar) and the māāy (serow)?”

“No”, said Naya, “The ākrū’s horns are not like theirs.” She pointed to the short curved horns on the animal skull board. “The ākrū’s horns were not always curved like this. They say that a long time ago, they were long and straight.”

Jeeha’s eyes widened. “How did they become curved then, Naya?”

Naya’s focus deepened. “Many years ago, Idu Mishmis were very confused about the ākrū. ‘What kind of animal is this ākrū’, they wondered? One of the Idu Mishmi men said, ‘Look at its slanted back, no other animal has a back like this’.

Another man said, ‘Look at its face. It looks like a goat, but is it a goat?’

Another one said, ‘But see, its horns are not like that of a goat’.

A young one said, ‘This animal looks like it has been put together from different parts of different animals!’ Everyone laughed.

The old hunter said, ‘Do not make fun of the ākrū. Ngōlō, the mountain spirit, will get angry. All the ākrū belong to him, no?’

‘No! They belong to us, the Idu Mishmi people’, the others said.”

“Then what happened, Naya?” asked Jeeha, slowly lying down and placing his head on his grandmother’s lap.

“Then? Both Ngōlō and the Idu people claimed that the ākrū belonged to them. For a long time, this continued. Then it was decided that there would be a competition between Ngōlō and the Idu people to decide. There would be a tug of war!

The Idu people invited everyone from Dibang Valley to take part in this competition. On that morning, Ngōlō and the Idu people met at an open ground, where the ākrū stood at the centre of the field.

All the Idu people took their place at the rear end of the animal, and their strongest hunter grasped the tail of the animal in a firm grip. The rest of the clan clamoured behind him, one after another, holding the one in front tightly by the waist. The mountain spirit Ngōlō, bravely stood alone in front of the animal and held its straight and long horns, one in each hand.

Both sides started pulling the animal towards themselves. The ākrū was also strong and stocky. It held its ground firmly as it was pulled in two directions. It was a tough competition between Ngōlō and the Idu.

Ngōlō kept a steady grip on the horns, even though the ākrū was tossing its head back and the Mishmis were pulling with all their might from behind. As it was being pulled forward, the ākrū’s heavy horns slowly started curving backwards and upwards.

The Idu people struggled with all their combined might to hang on to the tail. But they were no match for the powerful Ngōlō. By the time the ākrū’s horns had curved, the tail began slipping out of their hands, and suddenly, with a snap, most of it came away in their hands, leaving only a stub attached on the back of the ākrū!

Ngōlō won, and from then on Ngōlō claimed that the ākrū belonged to him.

And so, the tale goes—this is how the ākrū’s horns became curved, and why it has a body that slants downwards, and why it has a short tail.”

“Naya, have you ever seen the ākrū?” asked Jeeha.

“Very few people have seen the ākrū. Hunters who have trekked up to where the ground is covered with snow, often talk about the ākrū.

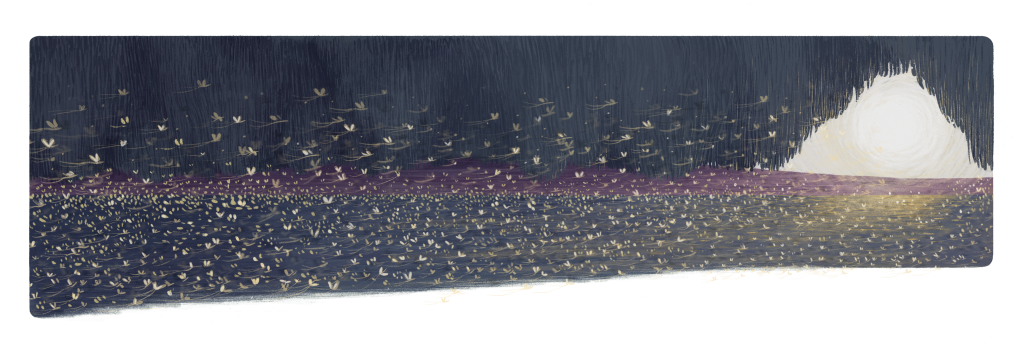

Some say they move in large numbers, even groups as large as 300! Who knows if this is true? I have never seen one,” said Naya.

Jeeha was now very curious to see this ākrū. He decided that one day, when he was older, he would trek up the Dibang mountains with his father, and who knows, maybe he would see an ākrū! And he fell asleep on Naya’s lap, dreaming of the ākrū, and the snow-covered mountains.

This is one of the many tales told by the Idu Mishmi. With the lack of a written script, most of these stories are orally passed down through generations. Idu Mishmi lore is rich with tales about mammals, birds, grasshoppers, and frogs, which also tells us a lot about their natural landscape.

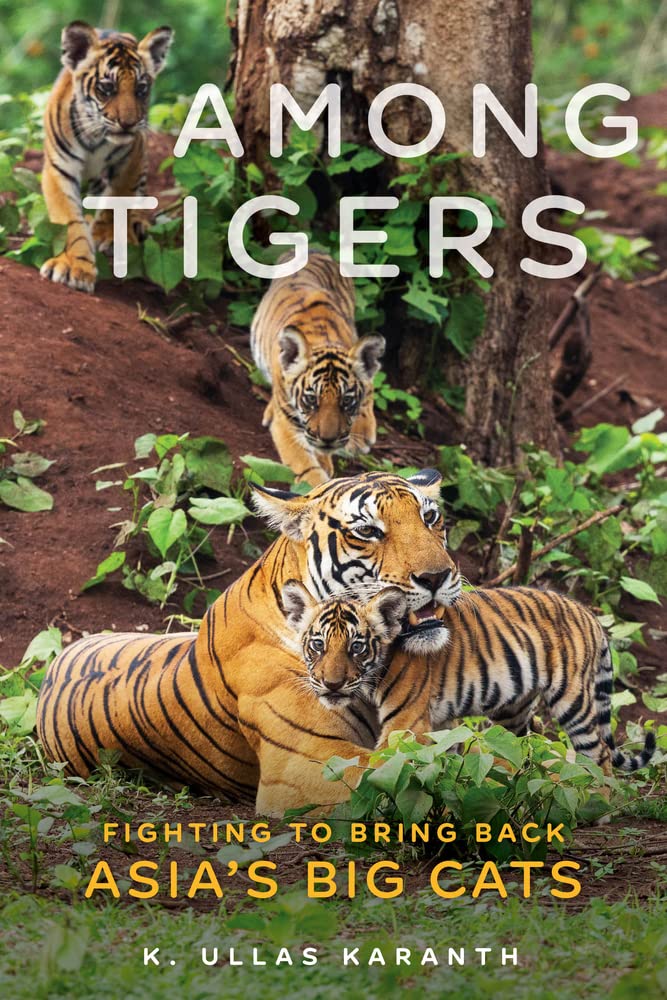

The takin is one of the animals that appears in the mythological stories of the Idu Mishmi. Locally called the ākrū’, it is a wild goat-antelope found in parts of Arunachal Pradesh, Myanmar, China and Bhutan. One of the four subspecies is the Mishmi takin (Budorcas taxicolor taxicolor). In Arunachal Pradesh, the presence of takin has been recorded on the higher peaks and ridges of Tawang, Siang valley, Lower Dibang valley, Anjaw, and southern Lohit districts. According to the IUCN, it is categorized as ‘vulnerable’, indicating that their population is decreasing. The Indian Wildlife Protection Act (1972) classifies the takin as a Schedule I species, a status similar to that of the tiger.

The Idu Mishmi are one of the three subgroups of the Mishmi–one of the 26 major tribal groups of Arunachal Pradesh. The Idu Mishmi live in the Dibang Valley and Lower Dibang Valley districts of Arunachal Pradesh, with a small population in the Upper Siang district. The Dibang Valley district is the least populated district in India, with a population of about 14000 Idu Mishmi. The region is known for its rich wildlife, beautiful snow-clad mountains, and high altitude wetlands. The Idu Mishmi are primarily dependent on swidden cultivation and forest produce: Life in the high mountains adjoining the Sino-India border is tough, because of the rugged terrain and harsh weather conditions. Animals are an integral part of their culture and life.

This is one of the stories narrated by Ananta Meme, a friend, an Idu Mishmi, and a resident of the Dibang Valley district. We have retold the story so that it can be shared with a wider audience.

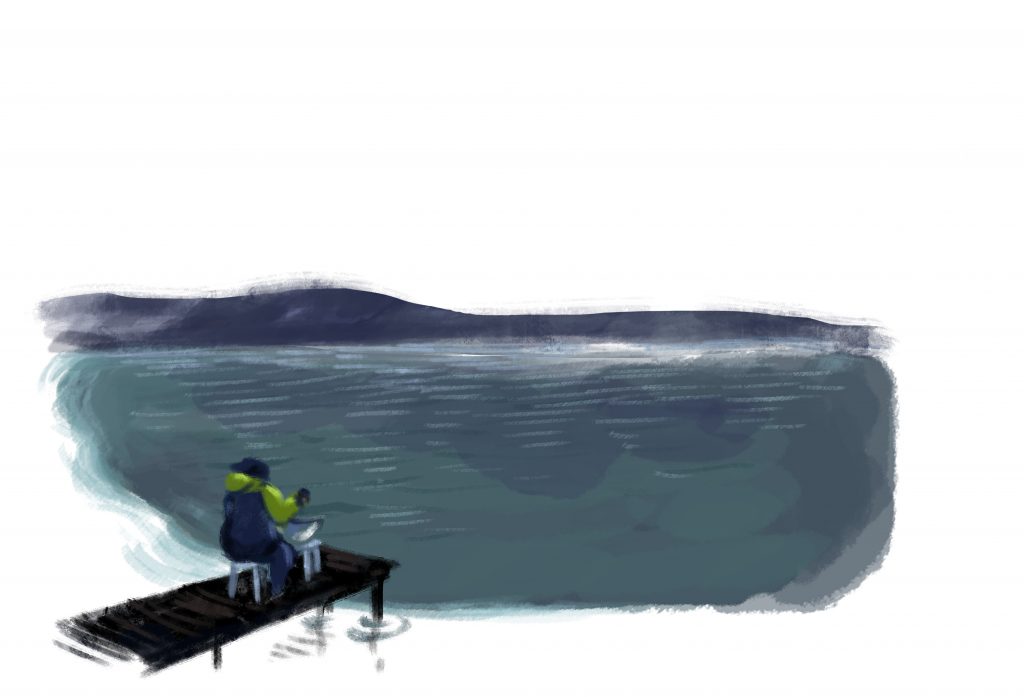

Dedication

I (AA), met Jeeha Tacho in 2012 when I started my PhD fieldwork in Anini, the district headquarters of Dibang Valley of Arunachal Pradesh. I stayed with his family, in Jeeha’s home for a year. He was 10 years old. We became good friends and spent time birdwatching, plucking fruits, and cooking. In 2017, Jeeha’s life was cut short in a tragic accident close to Etabe village. This story is dedicated to him.