The Elephant Task Force Report advocates transparency in all aspects of elephant conservation and calls for an administrative overhaul both at the union and state levels. As admirable as this effort is, do some of the recommendations need rethinking?

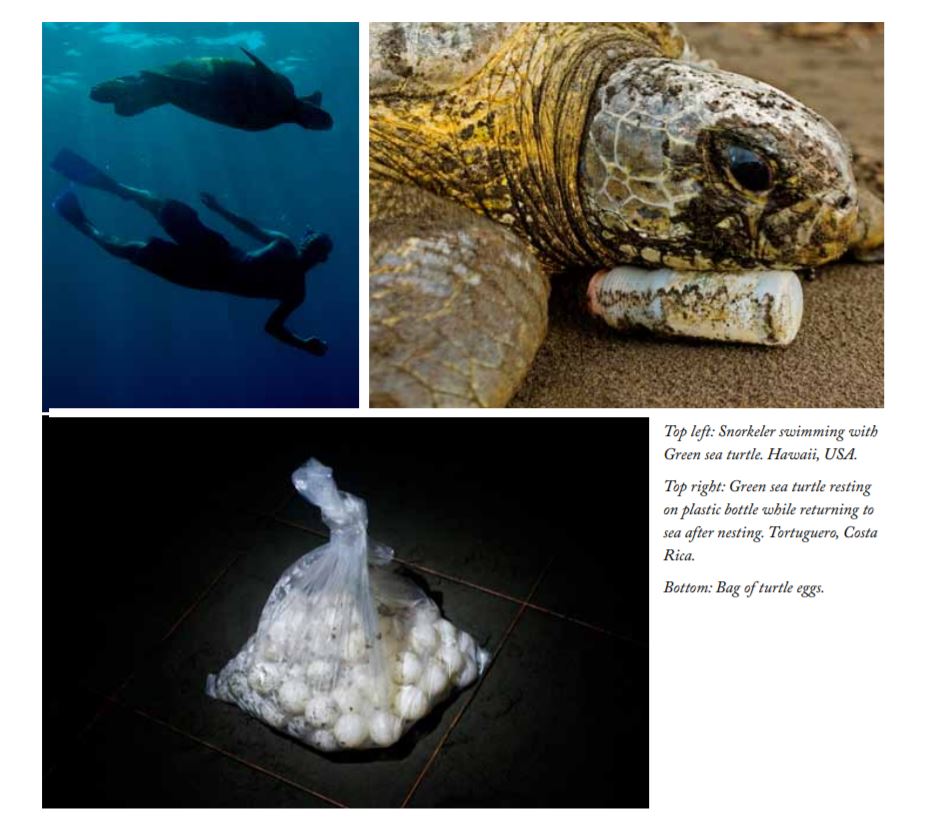

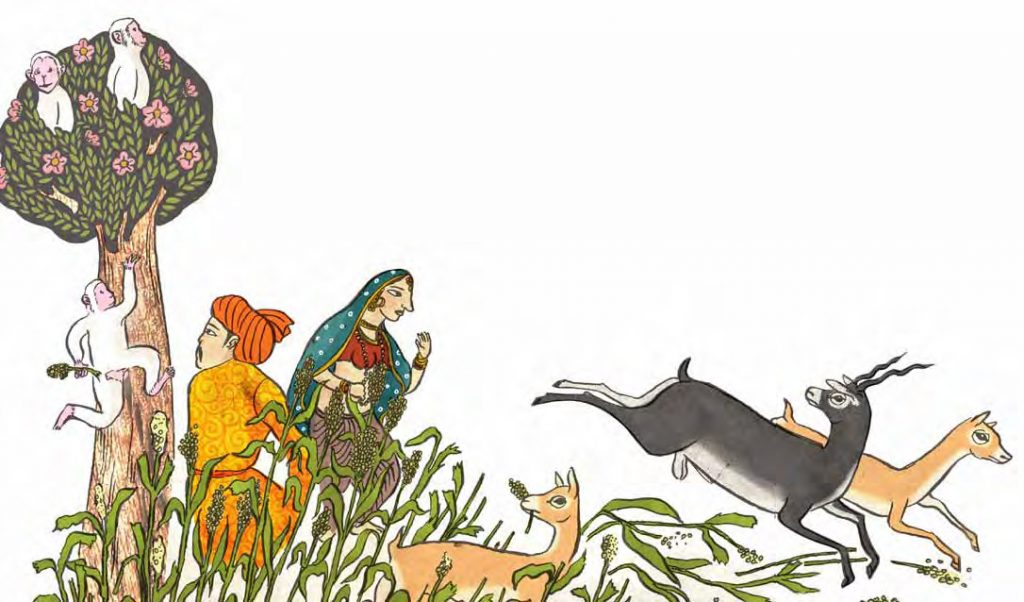

Prior to the software buzz, a bejewelled Maharaja on an elephant was an important brand icon for India. This acted as an important symbol for promoting the tourism industry. But in recent times ‘brand elephant’ has suffered a loss of reputation, at least in some parts of rural India where farmers suffer crop loss or injury/death of near and dear ones. Though some of us strongly advocate the preservation of elephants, certain sections of society, especially those who live in close proximity to this megaherbivore, do not share our sentiments about these difficult neighbours.

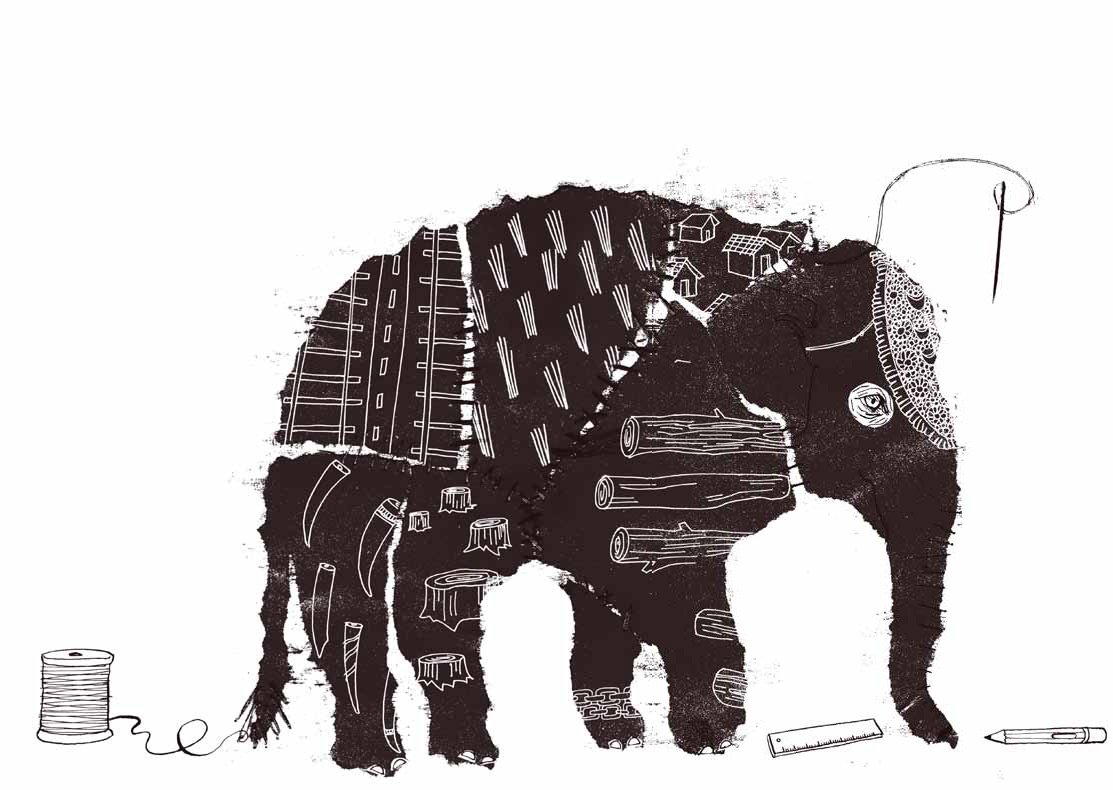

At the other end of the spectrum infrastructure project proponents (though crucial for the country’s economic growth) have knowingly or unknowingly ensured fragmentation and degradation of elephant habitats at a scale and pace that is monstrous. Hence, today, saving a large wildlife species such as the elephant has become the ultimate test of society’s willingness to conserve wildlife. India hosts the largest Asian elephant population and with an estimated 26,000 elephants it is home to half the world’s population. These pachyderms are spread over a geographical area of about 110,000 sq km, sixty percent of which is declared as 32 Elephant Reserves (ER).

A different concept than the conventional Protected Areas (PAs), ERs consist of a mixture of land categories. PAs (30%), Reserved Forests (40%) and private lands (30%) form the land tenure of ERs. Securing this landscape in pursuit of saving a flagship species is a challenging and daunting task, particularly as degrees of protection and land ownership vary within ERs. Combined with it is the ever expanding economy and crushing human numbers competing for space, sometimes with elephants. This is perhaps true for all large vertebrates that demand specialised food habits and/or range over wide areas. However, due its ability to inflict human fatalities, the conservation of elephants is a mammoth task compared to the conservation of any of the other species.

The increased tension due to human-elephant conflict and rampant retaliatory killing of elephants prompted the central Government to set up the Elephant Task Force (ETF) along the lines of the Tiger Task Force that was set up earlier in the wake of the tiger crisis looming over the nation. The import- ant assignment of ETF was to bring in long-term, pragmatic solutions for elephant conservation.

Interestingly, the task force was headed by a wildlife historian and political analyst, which is an indication of the issues related to elephant conservation that encompasses the broader social milieu. Other members of the task force comprised elephant biologists, conservation and animal welfare activists, and a veterinarian. The report was developed based on country-wide consultations with a wide array of people including people affected by elephants, elected representatives, officials of forest departments, wildlife biologists, conservation and welfare activists, mahouts, veterinarians, temple committees, and elephant owners, attempting a democratic process.

‘Gajah: Securing the future for elephants in India’, was recently submitted to the Government sans the intense media glare that the Tiger Task Force attracted. The report advocates transparency in all aspects of elephant conservation, and it is admirable that the report itself was immediately made accessible to the public on the Ministry of Environment and Forests’ website. The ETF has focused on a wide range of issues such as the elephant’s spread in the country, governance, habitat loss, protection and habitat management, captive elephants, human-elephant conflict, elephant research, and outreach.

Elephants and governance

Few Government-appointed committees have been critical about the way the public institution functions. Calling for an administrative overhaul both at the union and state level, ETF notes that there is lack of focus and attention at the highest level of the Government. ETF comments that though Project Elephant was set up in 1992 it has been “unable to take up leadership in elephant conservation”. A statutory body similar to the National Tiger Conservation Authority is proposed. This new body, National Elephant Conservation Authority (NECA) would require amendments in the Wild Life Protection Act 1972 (WLPA), to give it teeth under the law. A budget of Rs 600 crore (US $129 million) has been proposed under the 12th five-year plan for NECA.

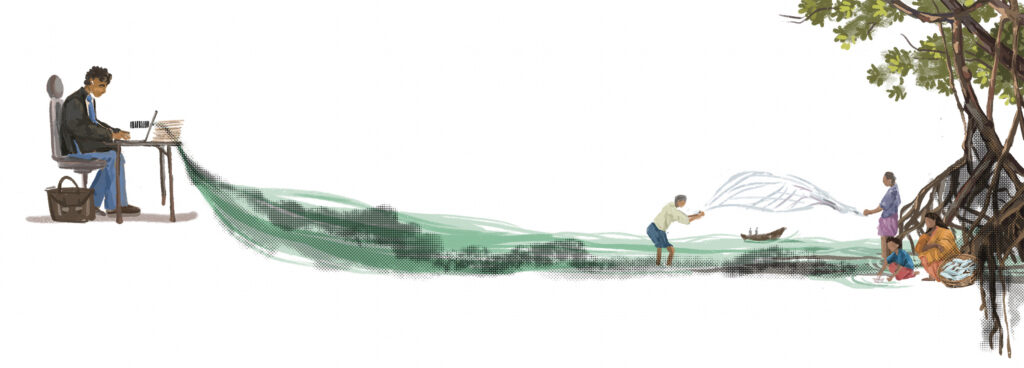

In a progressive idea, ETF recommends lateral recruitment of non-governmental personnel with requisite skills to be appointed in the NECA at the regional levels. To improve governance in management, Operational Reserve Level Management Advisory Committees comprising of elected representatives (MLAs, Zilla Panchayat, Gram Panchayat and Gram Sabha members), local conservationists, officers of railways, veterinary, and other departments, which would hold public hearings, are to be setup. An important feature that’s missing in our PA management is objective, ecological, and administrative assessment of performance. Independent evaluation of the ERs with performance indicators to measure progress is recommended to bring in transparency.

Defragmenting elephant habitats

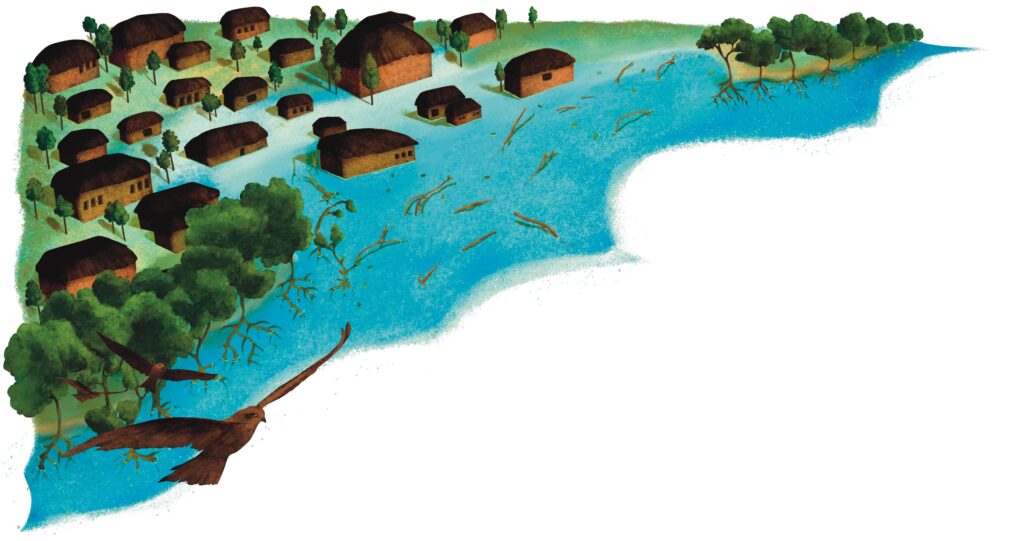

Recently there have been increased debates about the role of PAs in wildlife conservation. However, with crisis looming over some habitat specialist species it is becoming clearer that PAs act as core sites for source populations. Re-emphasising this, ETF calls PAs indispensable for elephant survival and has suggested that PAs be expanded to include critical habitats and corridors or else be declared as Community or Conservation Reserves as found fit.

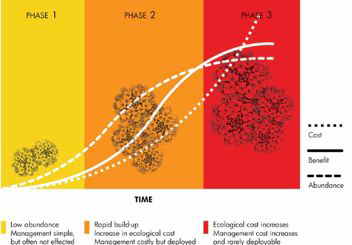

Expanding or declaring new PAs, however small they are, is a herculean task in the current socio-political situation. Opposing interests, whether legitimate or not, are too many. Hence declaring elephant corridors, as part of the PAs that as suggested by the ETF would be a challenging job to accomplish. The world over and in India elephants have experienced massive contractions of their geographical range due to modifications of their habitats and landscapes. This collapse of range needs to be halted if wide-ranging species have to be saved, and saved with minimum conflict with humans. Larger external pressures have pushed elephants into fragmented habitats and this needs larger habitat management processes.

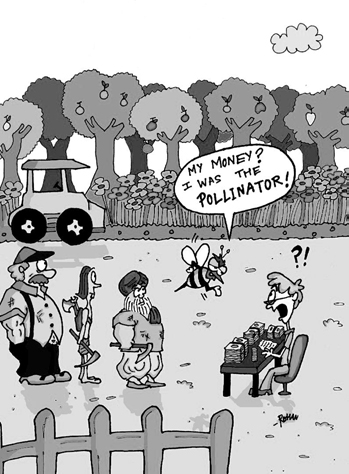

To reduce further fragmentation of elephant habitats it is recommended that entire ERs are declared as Ecologically Sensitive Areas under the Environment Protection Act. The EFT suggests that infrastructure development like mining within ERs be checked or permitted under strict ecological safety standards, and urges continuance of local livelihood activities subject to existing norms. To check diverting wildlife habitats without species specific criteria, a new approach termed as Elephant-Specific EIA (Environmental Impact Assessment) is suggested for permitting developmental projects within ERs. The ETF has also recognised the long pending issue of quality and rigor of EIAs and licensing consultants conducting EIAs.

Civil society has identified 88 critical elephant corridors across the country based on various ecological and social parameters. ETF has ranked the importance of these corridors and a Rs 200 crore (US$ 43 million) budget for corridor securement is proposed under NECA. Apart from this it is also suggested to use Compensatory Afforestation Fund Management and Planning Authority (CAMPA) for habitat consolidation and in particular for purchasing corridors. The corridors have been divided into two categories based on ecological priority and feasibility.

The report calls for rationalisation of ER boundaries based on ecological principles rather than the current ad-hoc boundaries. With this background the ETF has identified 10 elephant landscapes for prioritising suggested activities. There are few cases where forest land encroachment, especially for developmental activities or commercial plantations, has been dealt with seriously in the country. This soft approach on a serious issue has bolstered forest encroachers. On a positive note ETF has suggested amendment of WLPA so that a minimum fine of Rs 10 lakh and imprisonment of not less than two years be imposed on encroachers in ERs. On the issue of linear fragmentations such as railway tracks, roads, and high tension power lines, several suggestions including regulating night traffic passing through elephant corridors and bringing railway projects under the purview of EIA have been advised.

Other serious concerns

Another critical issue addressed is the way elephant habitats are managed in the name of ‘habitat improvement’. The report has set guidelines on management of surface water, forest road construction, and soil and moisture conservation activities in elephant habitats. This is an effort to inculcate scientific management of habitats and also prevent ‘leakage’ of conservation funds.

Applying the precautionary principle on the important international issue, opening of ivory trade finds no support in the report as it states that “no rationale, whether ecological, economic and ethical can justify international ivory trade.” Expressing unstinted support for wildlife conservation, the report states “in India species do not always have to pay to survive.” This should answer questions of culling, trophy hunting, and other similar conservation paradigms. Issues that are perhaps ubiquitous to most tropical countries such as improving enforcement effectiveness and staff recruitment at lower levels also find place in the report.

Education and outreach

Broaching the domain of conservation education, which is focused more on urbanites, the report has emphasised enormously on conservation education and outreach for communities living in and around elephant habitats. In a bid to take elephants to people, based on ETF’s suggestion elephant has been declared as a national heritage animal. Hosting the first International Elephant Congress, Elephant Range Exchange Programme, United Nations Day of the Elephants and setting up of the Asian Elephant Forum are other suggestions.

On the flip side

Certain recommendations made by ETF need some rethinking. It has gone with the old model of recommending MPs to represent in national level committees. Representation of MLAs from high conflict areas in the national level committees is important. The political dynamics of MLAs and MPs are different. Rural communities have an influential political voice but have better access to MLAs rather than MPs. MPs do not rely directly on individual voters to regain political constituencies like MLAs, but operate through other elected representatives and local leaders.

It should be mandatory that there is no financial link between the agency applying for permits and EIA consultants. This issue has been the crux in the bias shown in most EIA reports. It would have been ideal if this gap was identified in the report. Another serious concern in the report’s recommendations is about independent evaluation of reserve management. Though the suggestion of independent evaluation is highly valid, it missed the point that evaluators cannot be people retired from the forest services. As ex-officials evaluating their own colleagues and juniors, the outcomes might be biased.

Bringing paramilitary forces to improve protection might not be an ideal solution. As the report itself has highlighted, elephant conservation is as much a social, economic and political issue as it is biological. Protection forces need considerable understanding of local issues, familiarity with terrain, people (for information gathering), language, and so on. Alien paramilitary forces might only work in terrorist, insurgency infested areas but not under normal circumstances.

Finally

Overall the ETF has shown a strong will to democratise the way elephant conservation needs to go ahead and also how Government appointed committees can perform. Lastly, the task force projects a positive picture that “India can secure the future of elephants and their forest home”. This is unlike several other reports which project a gloomy picture. Hope the recommendations of the task force are implemented by the Government in true spirit.