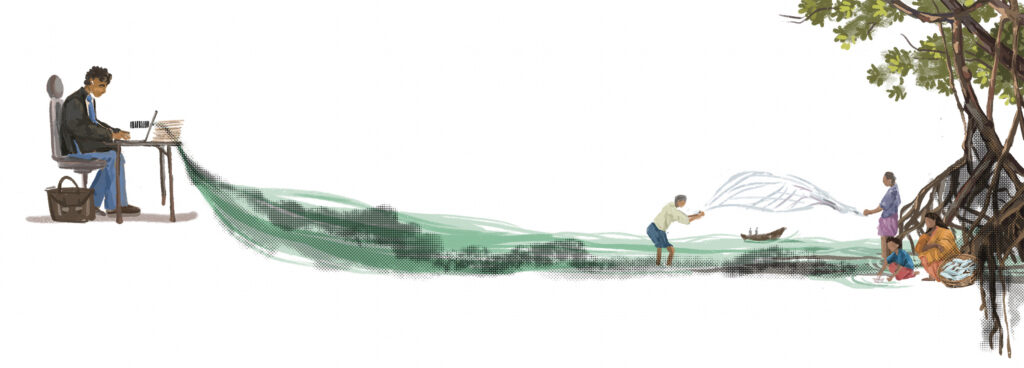

Around 150 years ago a British engineer working in South India, Arthur Cotton, came up with revolutionary ideas to move and use water. The aim was “to arrest the unprofitable progress of its (the Godavari) waters to the sea”*. He sought to link rivers both for irrigation and as a means of navigation and movement of goods. The 19th century made strides in the engineering field and as so often happens with new technologies and ideas, they are seen as a cure-all for problems of life. In this context, the idea of solving water shortages and floods through the movement of river waters was born.

The idea has floated around catching the imagination of some of India’s water resource planners for some time. Both Prime Minister Vajpayee and President Abdul Kalam were impressed by it and the idea has been pushed as a BJP ‘dream’. However, some erstwhile Environment Ministers, like Jairam Ramesh, has examined the idea and pronounced it “disastrous”. Even government agencies such as the National Commission for Integrated Water Resources Development Plan (NCIWRDP), after examining it carefully, considered it “unnecessary” and opined that the river basins could get all necessary resources from within their own area. River link schemes suggested in the 1970s were abandoned as technically or economically unfeasible.

Though we may still not fully understand our natural world, the 21st century has a far more developed knowledge of ecosystems and their crucial services than did the 19th, so while “unused” water may not provide direct financial gain, only the ecologically ignorant can regard a river’s natural flow as “unprofitable progress”.

It is extraordinary therefore that the Government still seeks to pursue an archaic engineering path for rivers. The river-linking scheme has had a momentum of its own; but, unusually for such a complex and far-reaching strategy, its biggest push came from the courts. While recording their limitation to make policy decisions and take expert views, the Supreme Court judges, in a 2012 judgment, nevertheless directed the government to constitute a “Special Committee for the inter-linking of Rivers”. This direction came in response to Public Interest Litigations (PILs) filed in the 1990s (No. 75 of 1998 and No. 15 of 1999) calling for the rivers to be nationalised and linked. These reached the Supreme Court in 2002 as Writ Petitions 668 and 512. The National Water Development Authority (NWDA), set up in 1982 to look at optimum utilisation of the river systems had completed the Detailed Project Report (DPR) of the Ken- Betwa link project in 2010. The Court ordered the new committee to evaluate this first.

The Court’s benign attitude to river-linking seemingly arose from the simplistically appealing view of it being a flood and drought mitigation strategy. But river ecology is more complex and farmers and scientists alike have long known that floods also have their positive aspects. Annual floods help remove agricultural toxins and bring crucial nutrients to the farmland while also recharging groundwater. Besides some of the worst flooding is actually caused by dams.

What is the Ken-Betwa controversy?

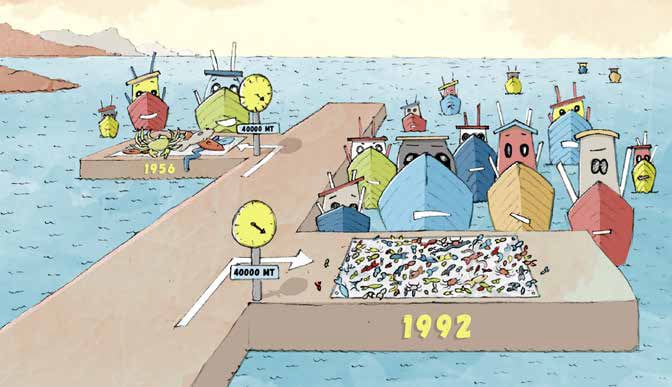

The Ken-Betwa project does not fit the flood-drought pattern. The Ken river flows through some of the most drought-prone areas of the country, mostly in Madhya Pradesh. In spite of this, the NWDA argues that it has “surplus water”. The Betwa is deemed “deficient” and hence the project seeks to take water from the Ken basin to the Betwa’s. In fact, both rivers rise in the Vindhya region and when one endures a drought year of low rainfall, the other does too. These are both areas with a long dry season so both rivers received most of their rainfall in the monsoon months – matching each other for drought and flood.

Although today proponents most loudly claim that this will bring water to the drought-prone farmers of the Bundelkhand region, the DPR of the project in fact states that “the main objective… is to make available water to water deficit areas of upper Betwa basin…” It is a project of water substitution. The Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) confirms that it is primarily for “the water-scarce Raisen and Vidisha districts”. Thus, in conception, it mainly looks to benefit areas outside Bundhelkhand, actually less “water-scarce” than its area of origin!

There are many ecological arguments against river-linking but it is also fraught with political and social landmines. Such projects bring to the table international disputes, interstate water wars, and even intra-basin – district level – conflicts to the table. Already those in the Panna district through which the Ken largely flows are wondering why ‘their’ water should be taken elsewhere rather than used to improve their own meagre livelihoods. Only 24% of the sown agricultural area of Panna is irrigated. Even Chattarpur and Tikamgarh districts of Bundhelkhand that the project has claimed will benefit, already have 65% and 78% irrigation (Minor Irrigation Census 2001).

It is hard to find a positive in this planned link or understand why the present government is pushing for it so strongly. Even the present Minister of State for Environment, Forest and Climate Change (Independent Charge) A M Dave does not seem wholly convinced: he has termed it “an experiment”. He believes the Ken-Betwa link should go ahead and an assessment of its impact on the environment be made after 5 to 10 years to see if others should go ahead. This is a strange view to hold when such projects require an Environment Impact Assessment exactly to assess this before the damage is done before a unique river system is irrevocably ruined.

An indifferent impact assessment

An EIA should bring relevant information to the fore so that the claimed benefits can be weighed and balanced against the damage, along with possibilities of mitigation so that an informed decision may be made. This has not been adequately done in the case of the Ken-Betwa link and the EIA fails on most of its main objectives and core values. The first of these is: “to ensure that the environmental considerations are explicitly addressed and incorporated into the development and decision-making process”:

A 77 m high dam is to be built on a river to siphon off around 1074 MCM (million cubic millimetre) of water, yet under “Impact on Water Environment”, the EIA comments: “no change in the regime of Ken River due to Daudhan dam is anticipated.” One does not need to be an expert to know that dams change the flow of water, hold back sediments and create barriers for fish – all of which would indicate a regime change.

Furthermore, in spite of it being the first dam and submergence area ever to be inside a Tiger Reserve, the EIA has no special section on its impact on biodiversity. Where broached, it comments somewhat incredibly: “The change in habitat is not very significant”. Ignoring the Panna Tiger ReserveField Director’s information that there are territories of two tigresses in the area as well as a large percentage of the park’s vulture breeding area, they write“there are no known breeding grounds for any of the RET (Rare, Endangered, Threatened) species within the project area.” The EIA’s credibility is also dented by its list of mammal species: this includes half a dozen not found in the area; indeed some on the list are not even found in India!

The proponents claim the project’s benefit will be a somewhat incredible 18-fold increase in agricultural production, and not a single environmental cost has been estimated to set against this. Furthermore, key aspects of the link have been ignored or separated as different projects. Thus even on its own terms, there is high doubt as to its efficacy, but examined from an ecological viewpoint the damage is huge and the EIA has glossed over and failed to appreciate or understand this.

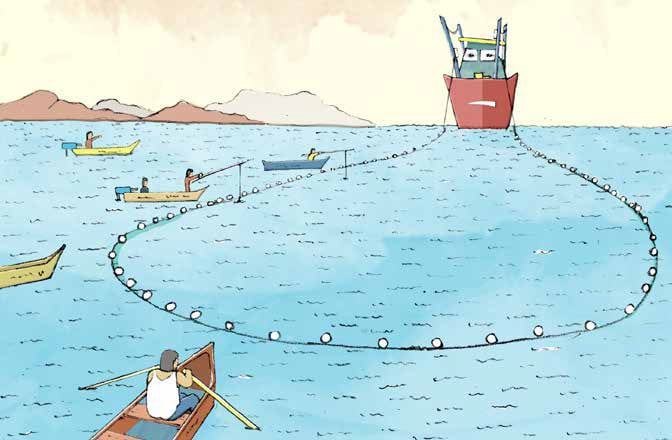

The EIA claims that the reservoir “will aid the conservation and management … of species such as Tor tor (Mahsheer).” This overlooks the fact that the reservoir would be fully inside a National Park and Tiger Reserve, whose authorities have already made it clear that the law will allow no such activities. It ignores the Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute’s study report comments regarding the “endangered” mahseer: “the river also holds a sizeable population of a famous sport fish Tor tor…the proposed dam would block the free movement of the fishes to their breeding and feeding grounds, hence lead to further depletion of the species from the system.”

Impact on endangered species

In the water, on land, and in the air – several endangered species will be adversely affected. In these decades of vulture depletion, Panna has been one PA where they have held on and now have a chance to come back. Seven of India’s nine vulture species are found here. For the long-billed vulture, especially, the unique steep cliffs of the Ken river gorge above Daudhan provide ideal nesting habitats. The Ken-Betwa project threatens to submerge these. And of course, the tiger: never before has a dam been built completely inside the Critical Tiger Habitat (CTH) of a Tiger Reserve. A CTH is “established on the basis of scientific and objective principles” and the Wildlife Protection Act requires it to be kept inviolate for the purpose of tiger conservation. Thus it is an area that should be a no-go for anything else. It is even more amazing that this dam and the submergence area, more than half of which is in the CTH and most of the rest in the buffer zone, is planned within an area that was considered important enough for a tiger that a new and costly project to reintroduce them to the area occurred. Over the last few years, the Panna tiger population has gone from 0 in 2009 to an estimated 30+ in 2017. The success of this reintroduction programme has been hailed worldwide. Yet now it can be jettisoned under an ‘experimental’ river-link project?

Occasionally the NWDA has tried to suggest that the submergence will bring benefit to the tigers and other animals of the reserve, but this is somewhat disingenuous. They cite the provision of water by the reservoir. However, the park already has the perennial river. They say the draw-down areas will attract and enhance the feature Joanna Van Gruisen population of herbivores, thereby increasing prey base. However, a nearly 10-year study on the ecology of Panna’s tigers by Dr. RS Chundawat shows that Panna already enjoys herbivore density and high prey biomass comparable with India’s best tiger reserves. The limiting factor for the tiger population in Panna is not food but space and connectivity. The submergence area would severely and catastrophically impact both these. Apart from the 90 km2 going underwater, the reservoir would completely bifurcate the park and block tiger access corridors to forests in the west. A tiger reserve already suffering from space mismatch, would be reduced by 162 km2, or more than 28%, according to the Field Director’s calculations – a death knell!

Not really a solution for drought

The key for Bundelkhand’s drought issues lies not in mega projects that will take 7-10 years to complete and bring debatable benefits even then. The way forward is to look to decentralised water management practises that can bring benefit within a year or two. Case studies in the area have established that local solutions are more effective in mitigating the negative impacts of drought and in enhancing farmers’ yields on a sustainable basis without altering the river’s natural process. Per acre, this also costs a tiny fraction of a megaproject.

The other side of water management that is given little attention is that of improving irrigation systems. In many areas, farmers still flood their fields for irrigation. Not only does this entail the use of far more water than required for the crop but it also removes nutrients and means the runoff takes pesticides and other pollutants back into the water systems. Sprinklers and drip irrigation can save as much as 30-70%.

Bundelkhand’s agriculture and wildlife, Raisen and Vidisha’s farmers, all the inhabitants of these areas can benefit if the management of water resources is approached with vision if 21st-century knowledge and awareness are fused with traditional local skills and understanding.

Outdated planning: The Ken-Betwa link project was designed more than 20 years ago. The hydrological and rainfall figures used in its justification were from even earlier. The effects of climate change impinge more with each passing year. Recent research suggests that rainfall is decreasing over ‘surplus’ basins and models show that water yield is increasing in deficit basins. Scientists conclude this “calls for a reevaluation of planning”.

Another paper shows that a minimum of 30 years of data is required to enable a realistic stream-flow assessment in rivers like the Ken. While many disagree with the categorisation of “surplus” for the Ken river’s water, it is hard to categorically refute, since the data on which they base this is not in the public domain.

Environmentally damaging engineering ‘solutions’ such as the proposed Ken-Betwa link are outdated in these – hopefully – more enlightened times. Many parts of the world have, with experience, learned the cost of dams – the USA has removed around 900 dams in the last 15 years and continues to decommission 60-70 annually. The dam age is passing. With her vision, creativity, modern skills, and traditional knowledge, India could leapfrog ahead to lead the world in a more sustainable and localised way of managing and using water.

References

Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute (CIFR). nd. Final Report on Study of Aquatic Biodiversity in the River Ken. Indian Council of Agricultural Research.

Ghosh, S, H Vittal, T Sharma, S Karmakar, KS Kasiviswanathan, Y Dhanesh, KP Sudheer et al. 2016. Indian summer monsoon rainfall: implications of contrasting trends in the spatial variability of means and extremes. Public Library of Science (PloS) One 11. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/ journal.pone.0158670. Accessed on April 6, 2017.

Gopal, B and DK Marothia. 2016. Seeking viable solutions to water security in Bundelkhand. Economic and Political Weekly (EPW) 51. https://www.epw.in/ journal/2016/44-45/commentary/ seeking-viable-solutions-watersecurity- bundelkhand.html. Accessed on April 6, 2017.

Jain, VK, MK Jain, and RP Pandey. 2013. Effect of the length of the stream-flow record on truncation level for assessment of stream

flow drought characteristics. Journal of Hydrologic Engineering 19:1361-1373.

Morris, H. 1878. A descriptive and historical account of the Godavery District in the presidency of Madras.London: Trubner & Co. Pp 418.

National Water Development Agency (NWDA). 2010. Detailed Project Report of Ken-Betwa Link Project (Phase 1). Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation, Government of India.

National Water Development Agency (NWDA). 2015. Ken-Betwa link project (phase-I): Environmental impact assessment and environmental management plan. Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation, Government of India.