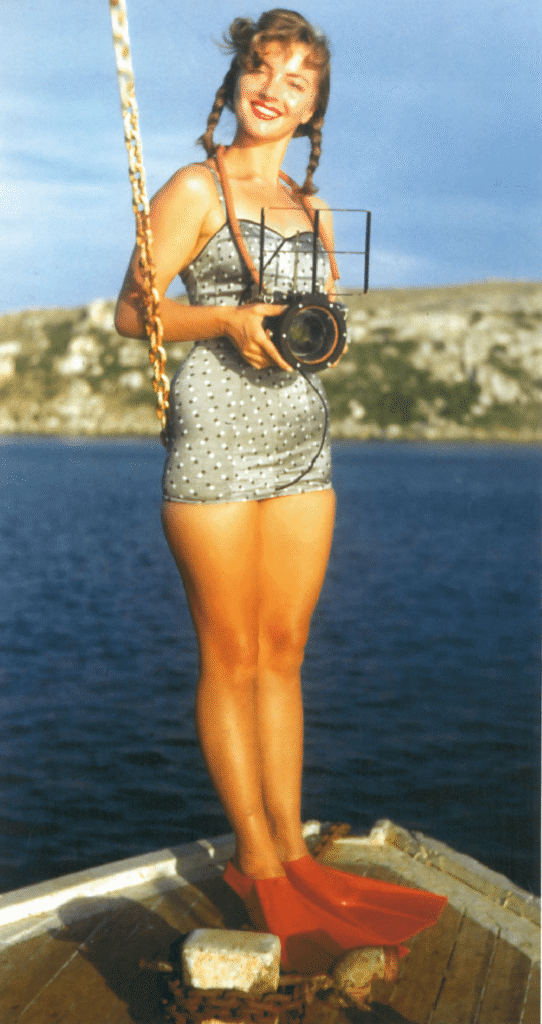

Foto 1. El humo de los incendios forestales en Chiquitanía, al este de Bolivia, ya se ve a primera hora de la mañana. Crédito de la foto: buna

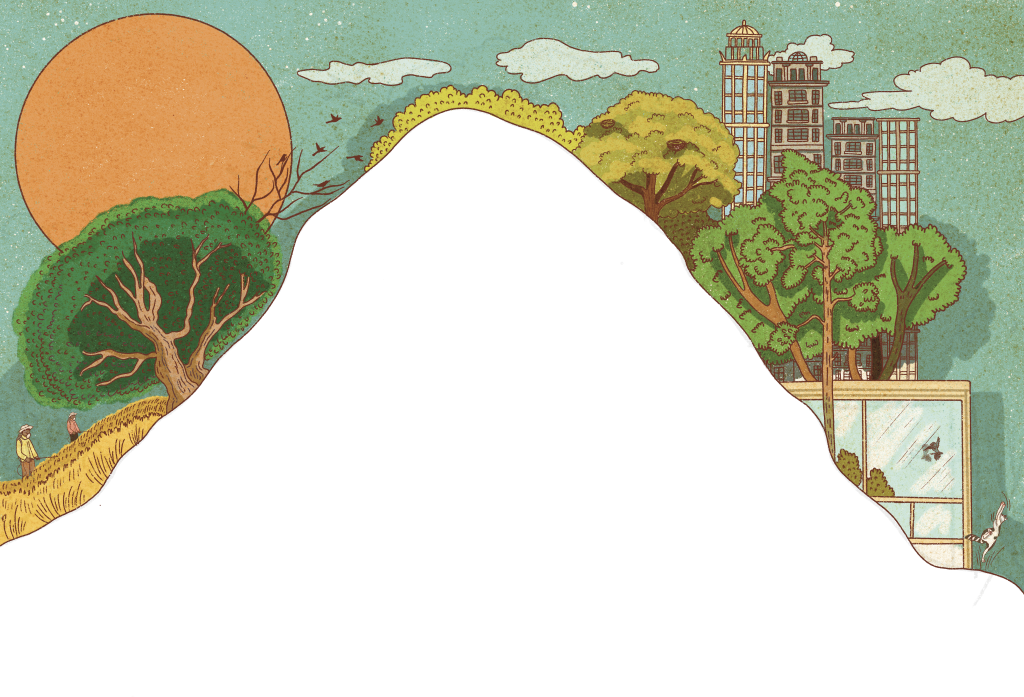

Bolivia es rica en diversidad biológica y cultural. Como parte de un proyecto de investigación sobre la diversidad biocultural de los paisajes agrícolas del país, he pasado cuatro años estudiando las interacciones entre las personas y las abejas en los bosques secos de Chiquitanía, en el este de Bolivia, hogar de varios pueblos indígenas, entre ellos los chiquitanos y los guaraníes.

Este trabajo se realiza en colaboración con la Fundación Tierra, una ONG boliviana dedicada al desarrollo rural sostenible de comunidades indígenas y campesinas, que ha estado estudiando los conflictos socioambientales en torno a la tenencia de la tierra en esta región. Sin embargo, nunca el conflicto fue tan grande y evidente, o tan denso, como en 2024. En ese momento, el país perdió cerca de 11 millones de hectáreas durante la temporada anual de incendios, vinculada al establecimiento de un modelo de producción agroindustrial que promueve la deforestación y el acaparamiento de tierras.

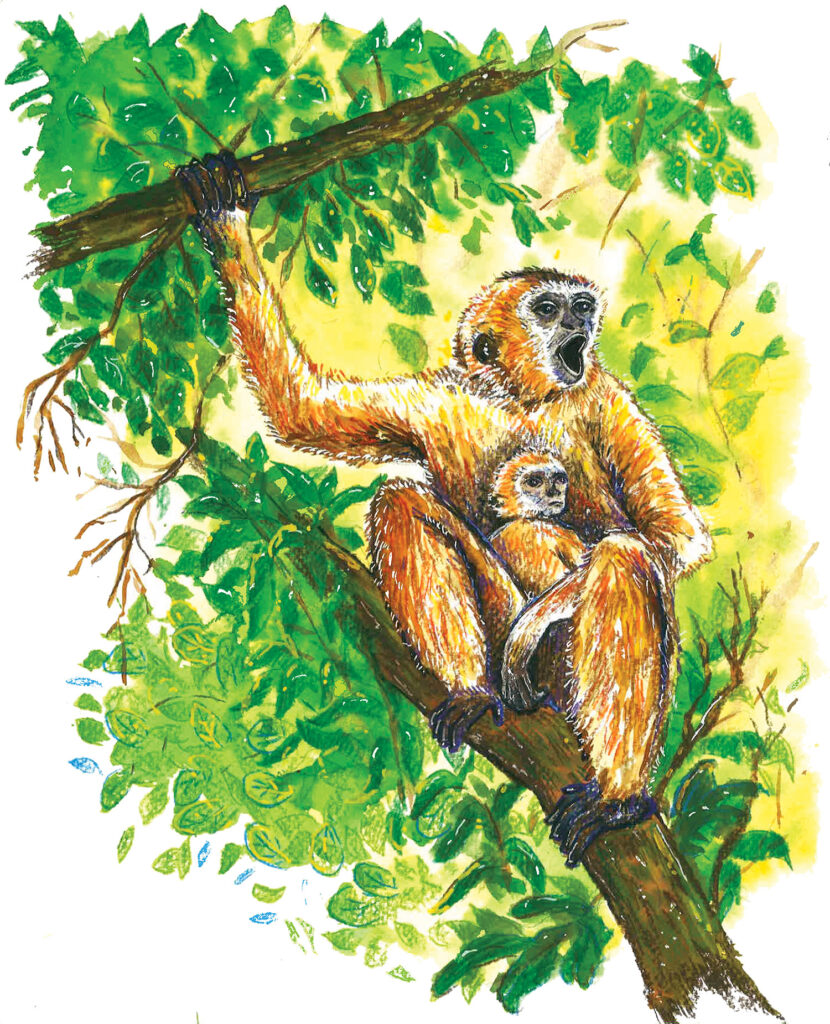

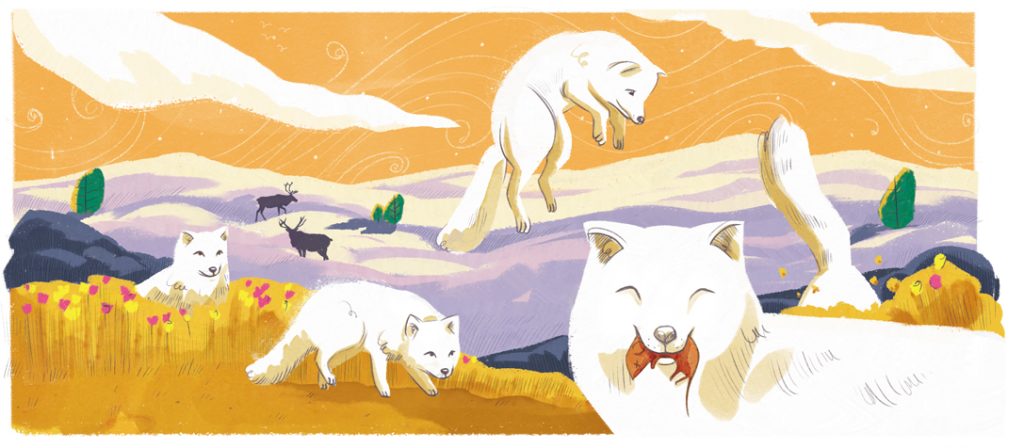

El contexto político en el que se está produciendo esto es complejo. Los incendios están impulsados por el interés en el desmonte de tierras para establecer monocultivos de soja y ranchos ganaderos, e involucran a varios actores, incluyendo medianas y grandes empresas vinculadas a los mercados globalizados, comunidades menonitas, pueblos indígenas de las tierras altas de los Andes y valles bajos que buscan nuevas tierras para cultivar o vender. Sin embargo, independientemente de quién sea el responsable, millones de plantas y animales han muerto en los incendios, e innumerables personas han enfermado debido a la pésima calidad del aire. Además, el humo de los incendios daña los ojos y los pulmones, y se impregna en el cabello, la ropa y las casas de las personas. El humo incluso envolvió la ciudad principal del departamento de Santa Cruz, donde la gente usaba mascarillas protectoras todos los días.

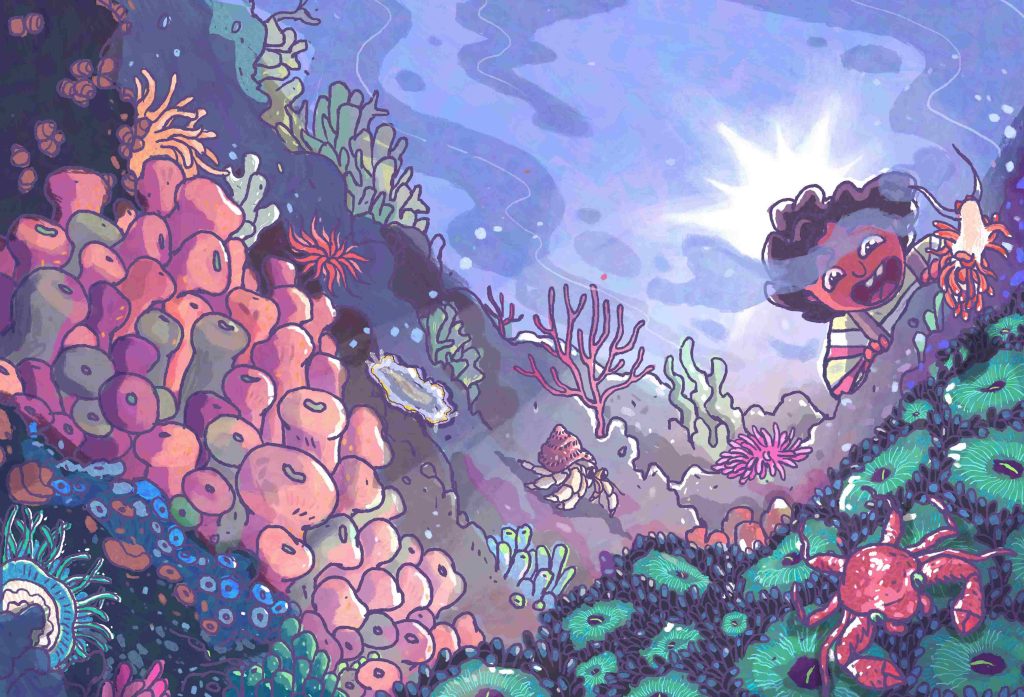

Cuando visitamos las comunidades locales de Chiquitanía, vimos plantas y animales quemados, y también observamos que las abejas silvestres no salían de sus colmenas tan a menudo en busca de alimento: parecían entumecidas. Como agroecóloga que estudia abejas, me preguntaba qué estaban comiendo, con el hábitat destruido y con pocas plantas con flores como fuentes de polen o néctar. Los sonidos de los insectos habían desaparecido casi por completo: ¿volverían alguna vez?

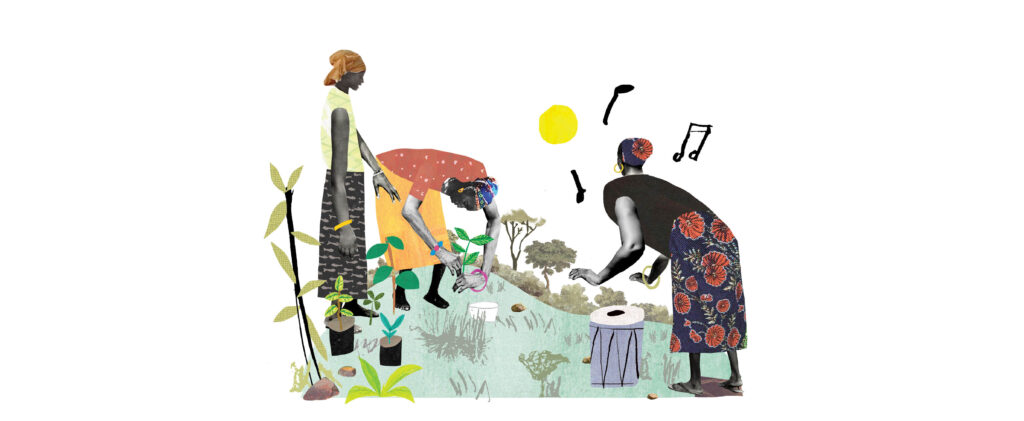

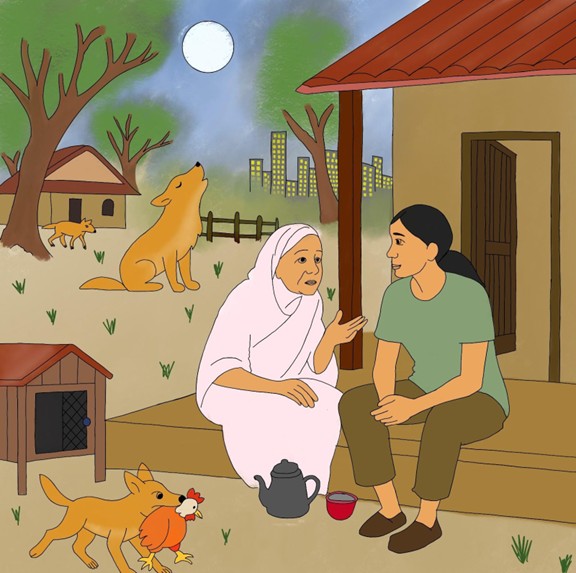

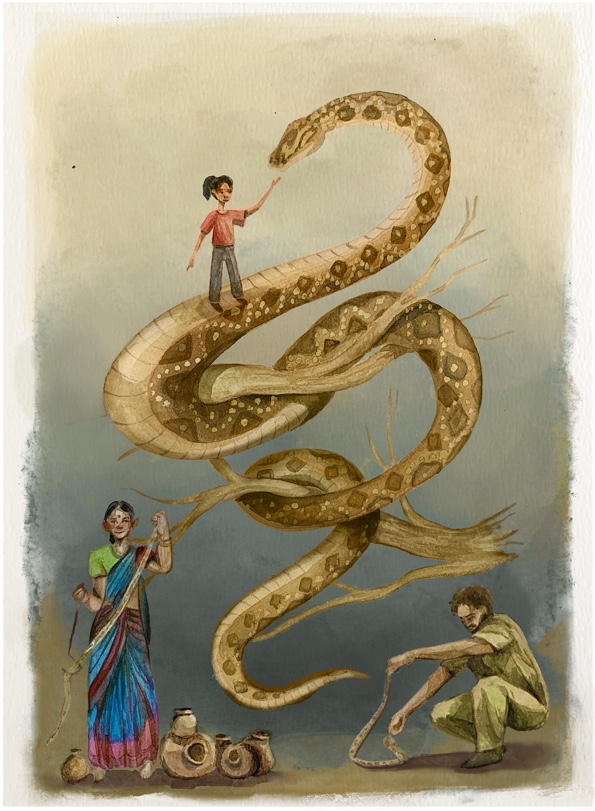

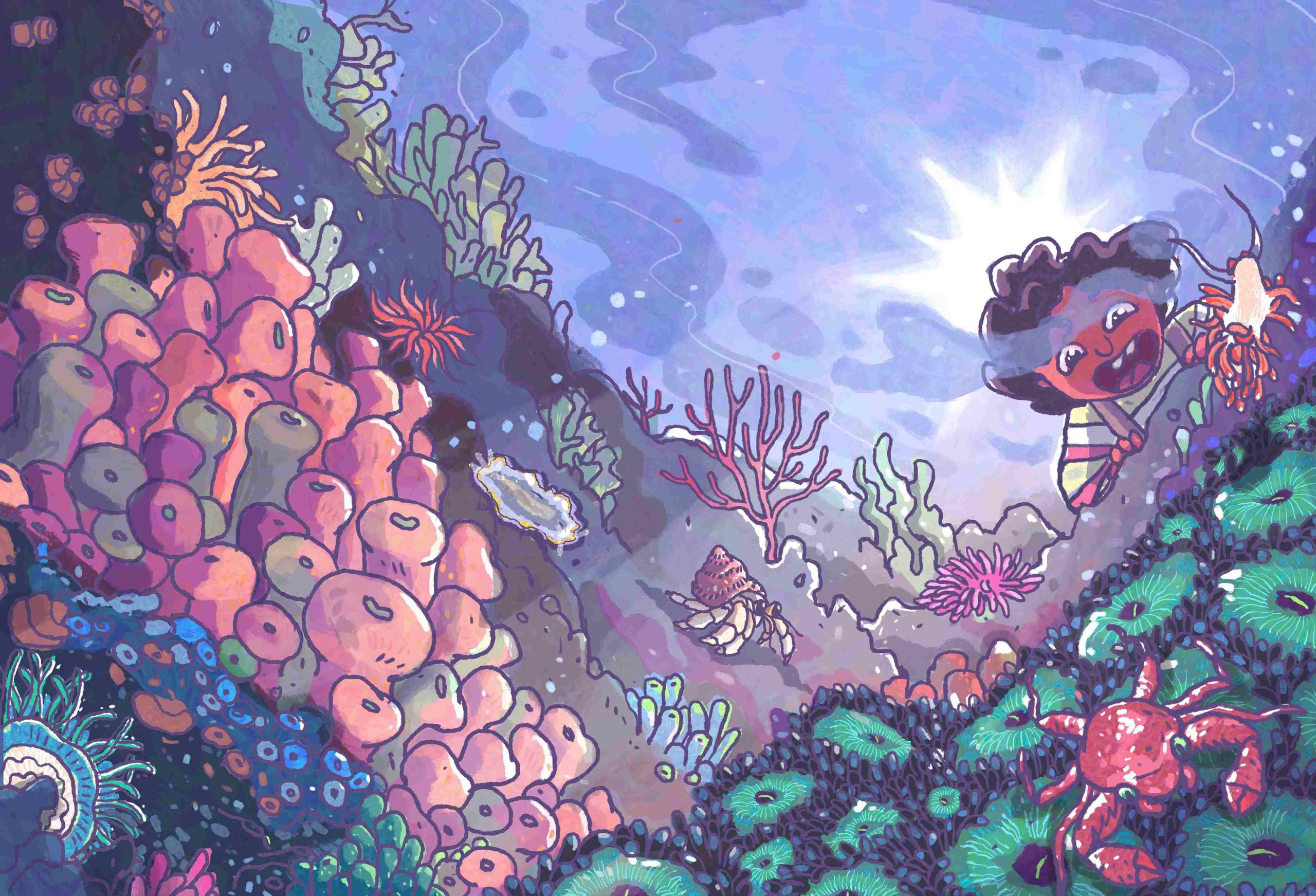

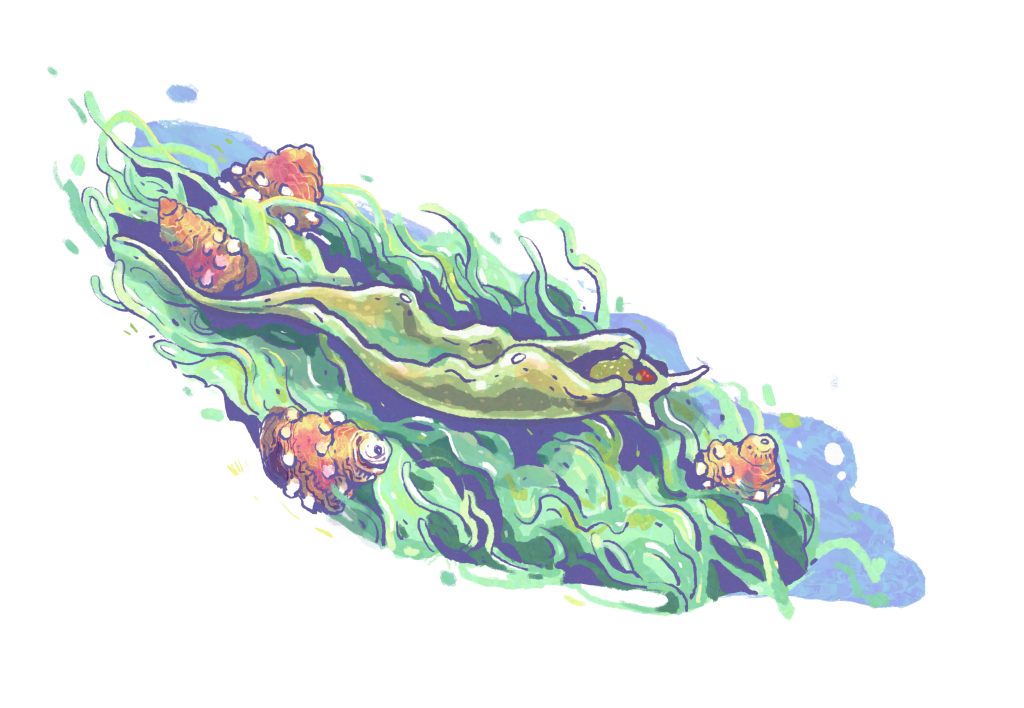

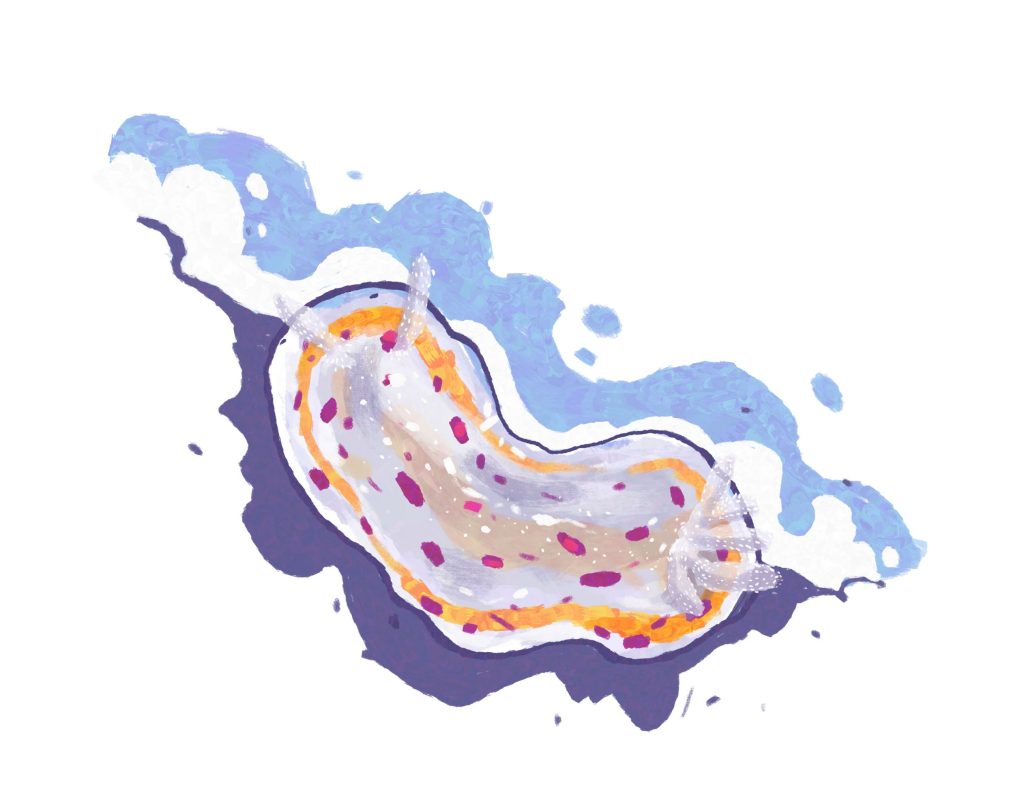

En esta sombría situación, queríamos recordar, junto con la población local, que todavía hay esperanza para un futuro mejor. Con nosotras estaba una joven artista muralista, Angy Saku, a la que le gusta representar la vida silvestre y la vida cotidiana de la gente en las áreas rurales. Y así decidimos utilizar el arte para trabajar con la comunidad, para observar y ayudarles a considerar sus fortalezas frente a las fuerzas destructivas que los rodean.

Con una persistente nube de humo sobre su cabeza, Angy Saku comenzó a pintar algunos de los temas de nuestra investigación en las paredes más a la vista de los sitios de las comunidades que visitamos. Mientras trabajaba, muchas caras curiosas comenzaron a rodearla. Los niños tenían varias preguntas que no dudaban hacer en voz alta: «¿Qué estás haciendo?», «¿Te gustan las flores y las abejas?», «¿Esa es mi abuela?».

Con el tiempo, se convirtieron en sus amigos y luego en sus colegas, cuando empezaron a pedirle instrucciones para ayudar con los murales. Angy Saku aceptó alegremente su ayuda y los guió en el uso del pincel y las formas de la naturaleza. No solo es una artista muy talentosa, sino también una buena maestra. Los padres de los niños también llegaron con el tiempo para ver, comentar e interpretar los murales. «¿Puedo hacerme una foto con el corechi ?», «¿Por qué no dibujaste a mi marido?». Se preguntaron muchas cosas entre risas y mientras compartían algo de comida. Casi nos olvidamos del humo y del dolor de cabeza que nos estaba causando a todos.

Después de diez días de marearnos con el humo, los murales estaban terminados. Representaban la diversidad biocultural a través coloridas imágenes de abejas y humanos interactuando, con un bosque seco en constante y rápido cambio de fondo. No es culpa de la población local que el «progreso» haya tomado la forma de incendios y deforestación, ni que sus devastadores efectos no siempre fueran visibles hasta que fuera demasiado tarde. Sin embargo, ver a niños y adultos identificarse profundamente con los animales y las plantas de los murales, así como ver a la gente observar detenidamente la composición de la obra de arte, muestra cómo el arte puede ser nuestro aliado en la lucha por proteger la naturaleza en estos territorios.

La investigación no tiene sentido a menos que se compartan los resultados, ya sea en forma de palabras o utilizando otro medio. La intrincada red de la vida es tan vasta que traducirla en arte nos recuerda nuestra conexión con ella o profundiza su comprensión. En cualquier caso, el arte puede despertar algo en nosotros, despertando la el sentimiento de que vale la pena proteger la vida, humana y no humana.

Lecturas adicionales

Benavides-Frias, C., S. Ortiz Przychodzka y T. Schaal. 2022. Nature on canvas: Narrating human-nature relationships through art-based methods in La Paz City, Bolivia. Letras Verdes 32: 67-87. https://doi.org/10.17141/letrasverdes.32.2022.5393.

Czaplicki Cabezas, S. 2024. Agronegocio sin frenos: Bolivia rumbo al desastre ecológico. Revista NÓMADAS. https://revistanomadas.com/agronegocio-sin-frenos-bolivia-rumbo-al-desastre-ecologico/. Consultado el 29 de octubre de 2024.Fundación Tierra. 2024. Bolivia: El fuego consumió más de 10,1 millones de hectáreas; 58% corresponden a bosques. https://www.ftierra.org/index.php/tema/medio-ambiente/1258-bolivia-el-fuego-consumio-mas-de-10-1-millones-de-hectareas-58-corresponden-a-bosques. Consultado el 20 de octubre de 2024.