I grew up in Kenya with a love for wildlife and the outdoors, hiking and camping. It was an obvious pathway for me to become an outdoor ecologist with the motto “If I can poke it, I can study it”. I designed my PhD and career to be outside, not confined within the walls of a lab. I debated the pros and cons of wading through a mudflat, mangrove swamp or insect-infested jungle vs. gliding through a coral reef—the choice was obvious! Since 1989, my research has been focused on coral reef resilience—particularly in the face of climate change—and the biogeography of the Indian Ocean.

Even as a child I was keenly aware of landscapes changing around me. As Kenya’s population and infrastructure footprint grew, the views across the escarpments of the Great Rift Valley transformed from wide open savannahs and dry volcanic slopes in the 1970s to squared-off, dense patchworks of shambas (farms), trees, houses, and growing towns. When would this system break? Or less dramatically, shift to a new state? I always wondered how people perceived their shifting context and their complex daily interactions with nature in the landscape—their matrix of uses—and the ever more complex mix of cultures and social norms?

When the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were first formulated, we all focused on ensuring ‘our system’ was represented. Hence, the ocean science and conservation communities were over the moon with SDG 14 ‘Life below water’—to conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development. Then followed a few years of grumbling over wording and targets, indicators and investment, and concern over being siloed away from the other goals, before diving into the interactions between goals and targets, and navigating trade-offs. The goals became illustrated in different ways, the most successful conceptually being the wedding cake model. It appropriately placed nature as the foundation for everything, which set the context for society, and both nature and society together set the context for the economy. This led to a three-tiered cake with the ‘social goals’ in between the ‘nature goals’ and ‘economy goals’.

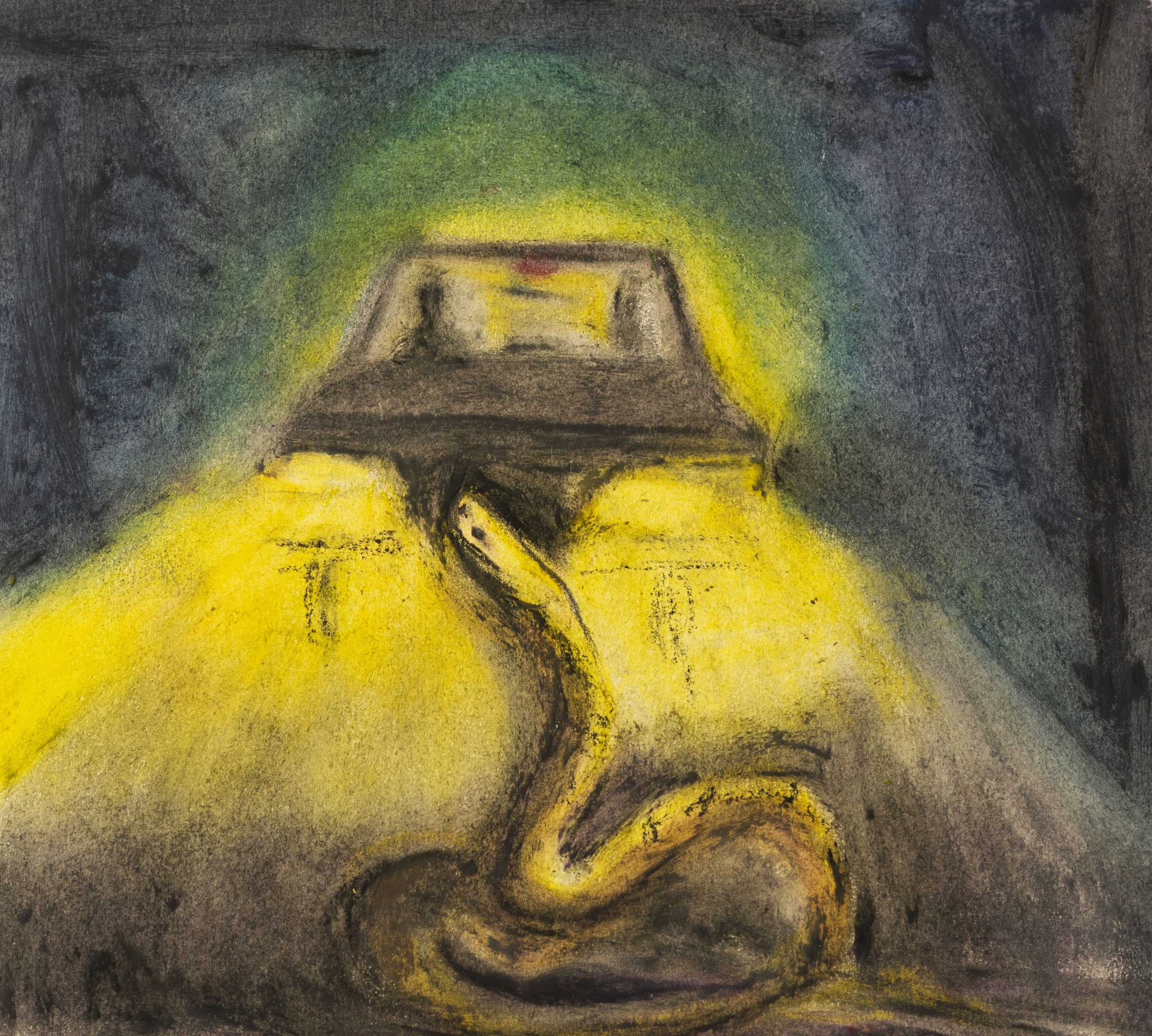

In many ways, I have always thought the SDG story was obvious—it’s an expression of the three pillars of sustainable development, where nature, economy, and society must strike a balance. I came to see the goals as the world’s almost 200 countries agreeing on a ‘minimum set’ of 17 ‘inalienable rights’. In a different year or month or if the balance of countries or contributors had been different at a crucial point in their negotiation, a slightly different set of goals might have been identified. But most importantly, whether 16 goals or 18, they give us a common language through which to negotiate sustainable development. And indeed that language does not need to be complicated—the goals can be simply expressed in 140 or so words (see Obura 2020), founded on the ‘nature’ goals, then up through the ‘economy’ to ‘societal’ goals and finally the enabling goals that make all this happen, as illustrated in the stack of goals (Figure 1), inspired by foliaceous corals.

The goals were negotiated at national levels, and they have permeated international discourse and the framing of all global institutions, from biodiversity to climate change to health and human settlements. But within countries, in sectoral entities, at local government levels, in businesses, and for ‘the people’, the SDGs have remained esoteric. Many are ignorant about them, question what they are, or fail to relate to them as they go about their daily lives.

The most common depiction of the SDGs—the rectangle of brightly coloured squares—shows no interactions or connections, no curves or subtleties, no interdependencies or overlaps among these 17 core elements of human living. Other depictions resonate more—circular depictions allow links among goals across the middle, the wedding cake version expresses a model of sustainable development—yet, people don’t feel how the goals relate to their lives. So, I decided to experiment with a new approach, to explore how local interests can be expressed through the lens of the SDGs. Since I work on coral reefs, the obvious starting point was a coastal fishing community in Kenya, expressed in the form of a story.

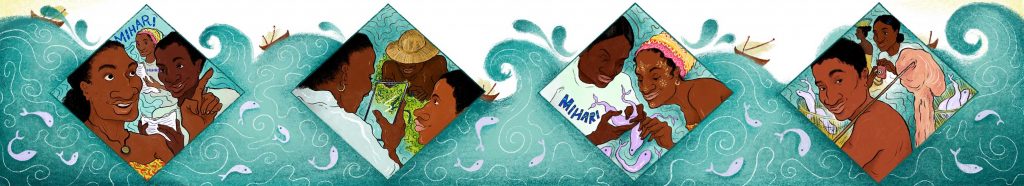

The Story of Mariam and Hamisi

Mariam and Hamisi live from the sea. He catches fish, which she sells 3–4 days a week in the local markets, their combined income paying for school fees, their health needs, repairing their house, etc. This evokes a number of the goals—from fish catch and their jobs and income , and the benefits to their household through nutrition , income , health , and gender roles .

Their livelihood is entirely dependent on the local reef , which also sustains the broader fishing community. Through its representative fisher association,

the community has co-management responsibilities with the local government to manage its members’ fishing activity,

including by establishing closed areas to enable reproduction and regeneration of fish stocks.

The closed areas attract interest from the local tourism sector, which is growing with coastal intensification and small-town development , bringing additional income into the local community and diversified jobs for local tourism operators, shopkeepers, and others . As interest in marine biodiversity and development impacts increases,

a range of community groups, non-government organizations and even researchers , engage with local issues to maintain natural assets and support diverse social programmes. Having gone to college

Mariam and Hamisi’s daughter not only works in the town as an electrician, but invests in a cold-store business to link her family and other fisher households to local markets.

The seascape is experiencing impacts from climate change , with the coral reefs bleaching and losing coral twice in the last decade, stimulating local leaders to lobby the government for climate action and commitment to the Paris Agreement. Conscious of the international travel that brings tourists, the business association puts in place varied climate mitigation and adaptation actions, including through replanting of coastal forests and mangroves, and committing to solar and other renewable energy technologies .

As stakeholders in the land- and seascape engage, the local government authorities establish platforms to facilitate broader participation and engagement, incentivising individual actions towards sustainability, and removing barriers to innovation and action. To ensure all interests are addressed, firm commitments to equity are made

across income and stakeholder groups , for women, children and vulnerable groups

So what?

What might this SDG story approach help to achieve? As Kenyan and other societies grow and blend, I feel the opportunities for decision makers to consider all factors and make decisions that agree with everyone’s worldviews diminish. Diversity is good, both in nature and among people, but it does make consensus more challenging, particularly as space (physically and metaphorically) declines and limits loom larger over peoples’ choices.

I feel the only feasible way forward across so many contexts around the world is through alignment around common principles. Done right it means that people can trust that choices are mutually supported, and at least not conflictual. The SDGs, adopted by 193 of the world’s countries, provide such an opportunity for alignment. I believe they might be even more successful at local levels, where their interdependencies can be tangibly experienced, and all people or actors may be more visibly accountable for their actions, such as if they go fishing in the wrong zone.

The SDGs enable alignment around what is too complex to command and control. For example, consider now in the context of COVID-19; if a business owner, a farmer, and a fisher all adopt SDG principles, they can follow their primary interests with due regard for not harming each others’ health and other interests, or those of any other local case-holder of the 14 other goals. Inherent in the model is that awareness and knowledge (goal 4) and good governance (goal 16) are necessary to mediate and assure alignment among stakeholders, and to ensure the burden of impacts and responsibilities is equitable (goals 5 & 10). Further, applying an SDG narrative within a local jurisdiction may help establish social safety nets to minimize risks of destitution (goal 1) and hunger (goal 2) during a common crisis.

This narrative approach may help to link the biggest picture worldviews with the local. 2020 and 2021 have emerged as ‘super years’ for framing both climate and biodiversity goals for decades to come, with the world being brought to its knees by a sign of things to come—the COVID-19 pandemic. Climate (goal 13) and biodiversity (goals 14 and 15) are each contained within the SDG framing; in fact, the Convention on Biological Diversity’s post-2020 global biodiversity framework is premised on a theory of change defined by the SDGs. Thus, from this global scale down to the local, can conservation and development finally walk hand in hand, such that people and nature interact directly and positively, living out individualized storylines of sustainable development? There are many campaigns vying to capture the collective imagination to deliver on the emerging global goals, in biodiversity, climate, and other domains. However, we will need approaches that are fully nature positive, people-positive, and economy-positive to enable their integration and aggregation to truly achieve sustainability from local to global scales.

Further Reading

Obura, D., Y. Katerere, M. Mayet, D. Kaelo, S. Msweli, K. Mather, J. Harris et al. 2021. Science 373: 746–748. DOI 10.1126/science.abh2234

Nash, K. L., J. L. Blythe, C. Cvitanovic, E. A. Fulton, B. S. Halpern, E. J. Milner-Gulland, P. F. E. Addison, G. T Pecl et al. 2020. To Achieve a Sustainable Blue Future, Progress Assessments Must Include Interdependencies between the Sustainable Development Goals. One Earth 2, 161–173.

Obura, D. 2020. Getting to 2030 – Scaling effort to ambition through a narrative model of the SDGs. Marine Policy 117:103973.

The Global Goals for Sustainable Development Goals. https://www.globalgoals.org/