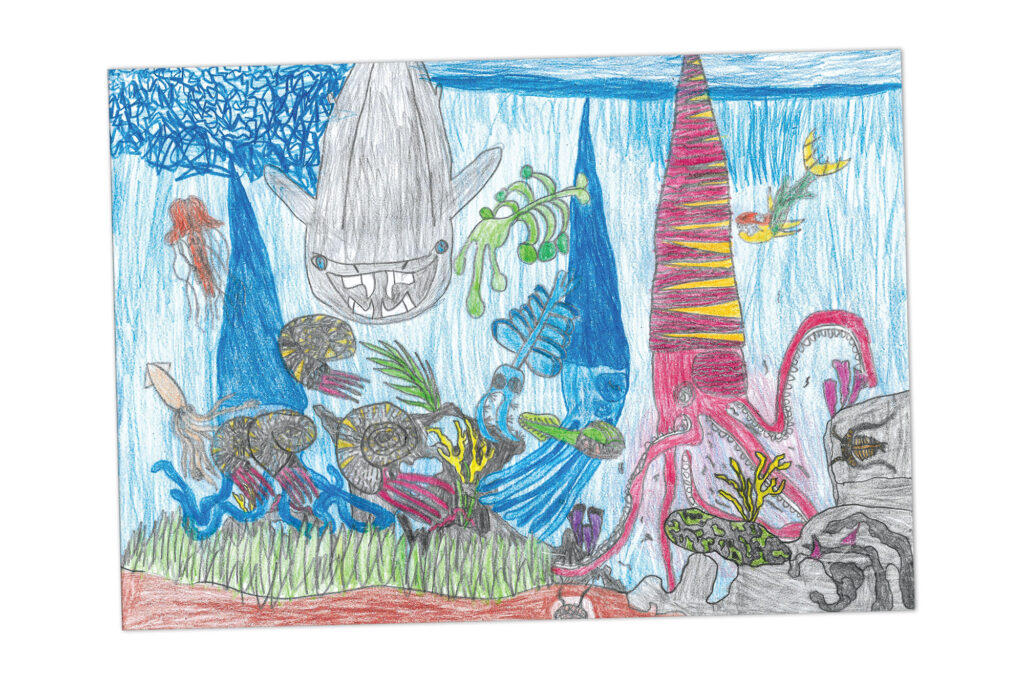

Feature image: A conceptual illustration arguing a multifaceted, and democratic approach in managing forest-, and human-health. Design by V. Jithin; Icon credits to Pixabay.

In 2023, the theme for the UN’s International Day of Forests was ‘Forests and Health’. Although not new to a lot of us, recent pandemics and the rise of emerging infectious diseases made this theme more relevant than ever before. While global schemes like One Health conceptually embrace the multifacetedness of the forest-human health relationship, local implementation of such projects face a lack of participatory approaches and awareness at the individual level. Hence, we argue here for a fresher, more democratic approach to managing forests and our health.

What is a forest?

For each of us, the definition of a forest can be different. Is it merely a large patch of trees, a verdant valley, our primary home or something else entirely? From being a source of timber to producing oxygen, can forests exist beyond the services they offer humankind? Typically, our schools and society illustrate forests as a collection of trees. This often leaves out many elements of nature that are critical in shaping forests. Can forests be seen as ecosystems, where plants, animals and other organisms interact with each other to form a lively network? Or a landscape that serves as a vital lifeline for diverse forms of life including us? An entity that transcends political and social boundaries?

It might feel as if modern humans have come a long way from being hunter-gatherers, but in reality, we are always interacting with forests—directly or indirectly—irrespective of our location in an ‘urban jungle’ or near an actual forest. Except for a few indigenous communities, forests are often considered a separate entity from humans. Consequently, we forget to acknowledge that forests influence our lives and we influence their existence. Nevertheless, at certain points, we realise the power of these invisible connections. This is especially true when we consider human health—a key value in our lives.

Forests are crucial for human health

Health encompasses more than the basic functioning of organs or clinical vitals. It includes our physical, mental and social well-being, often closely associated with our surroundings. An IPBES report published in 2019 classified several human health-related benefits from forests, such as nutritional availability, prevention or buffering the impact of natural hazards, prevention of communicable and non-communicable diseases, improved mental health and medicines of forest origin.

Cardiopulmonary diseases, diabetes and cancer are known to cause 71 percent of global deaths, of which 77 percent occur in low and middle income nations. Although there are no direct studies that trace exactly how forests protect us from such diseases, several studies have indirectly shown that forest-related activities (walking, running, climbing, swimming, etc.) enhance our bodily functions by improving our immune system, as well as reducing blood pressure, mental stress and anxiety. Other studies have shown how exposure to forests supports the growth of healthy children, and their importance in reducing pollution-associated mortality—a major issue in developing countries.

Another important health-related benefit is the production of synthetic medicines as a result of intensive scientific research in forests. Many of these medicines have their origins in our traditional knowledge and the bioactive compounds that are serendipitously discovered from various organisms in our forests. For example, Himalayan Yew (known locally as ‘thuner’) is a source of taxol, which is used to treat cancer; ‘Arogyapacha’ (Trichopus zeylanicus), a plant endemic to the southern tip of the Western Ghats and used by the nomadic Kani tribes, resulted in an anti-fatigue formulation; and the Cinchona tree gave us the antimalarial drug quinine.

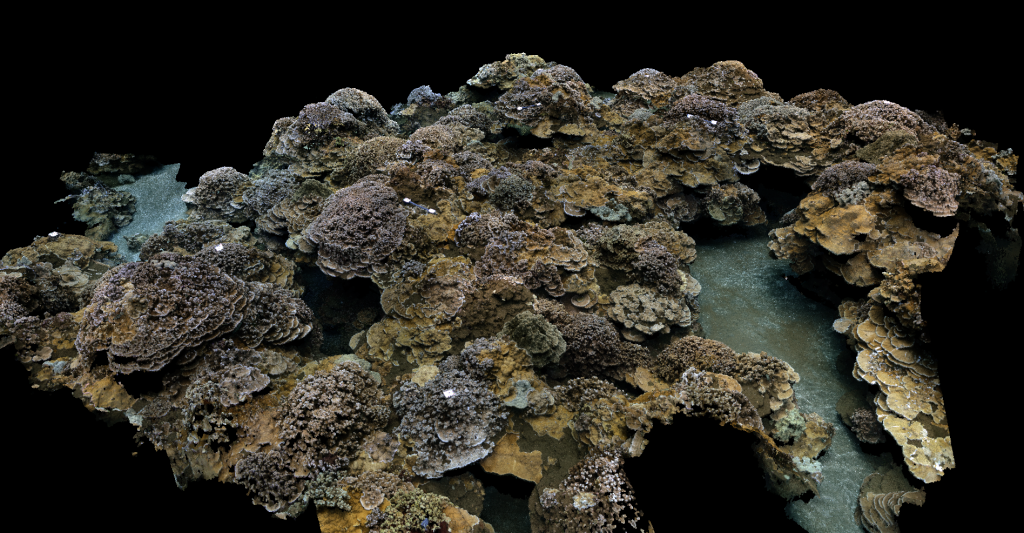

Hence, forests are often described as “repositories of medicines that can make pivotal changes in our health and scientific field”. However, it is regrettable that many undiscovered organisms with potential benefits are disappearing from these repositories before scientists can study and document them. This loss is particularly concerning because these organisms may hold valuable insights into ecological processes, provide new sources of medicine or contribute to agricultural productivity.

Emerging diseases and increasing fear of forests

Forests are invaluable. However, the recent emergence of zoonotic diseases like MXPV (monkeypox) across the globe and re-occurrences of regional diseases like the Kyasanur Forest Disease in the Western Ghats, have contributed to the multi-layered fear of forests among common people. Increasing human-wildlife interactions without precautionary measures often lead to disease transmission from animals to humans. For example, monkeypox occurs when humans come in contact with or consume infected animals, such as rats and squirrels. It has been shown that MXPV spreads due to land use changes associated with forest disturbance in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The spread of novel diseases due to forest degradation has become a serious concern globally. When we reflect on recent events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, it is clear that such diseases have affected everyone, regardless of race, gender and nationality. Half of infectious diseases have been known to originate from animals or spread through them as intermediate agents—scientifically known as zoonotic diseases—and a third of these are triggered due to deforestation, and increased human activities in the interior forests, usually associated with land use change. Human-made changes in forest landscapes increase the chances of disease-causing organisms crossing species barriers, as often the pathogens are hosted by a specific group of host organisms and reach humans eventually. To prevent these spillovers due to increased human-wildlife interactions, we need to discourage the alarming rates of forest land conversion and degradation.

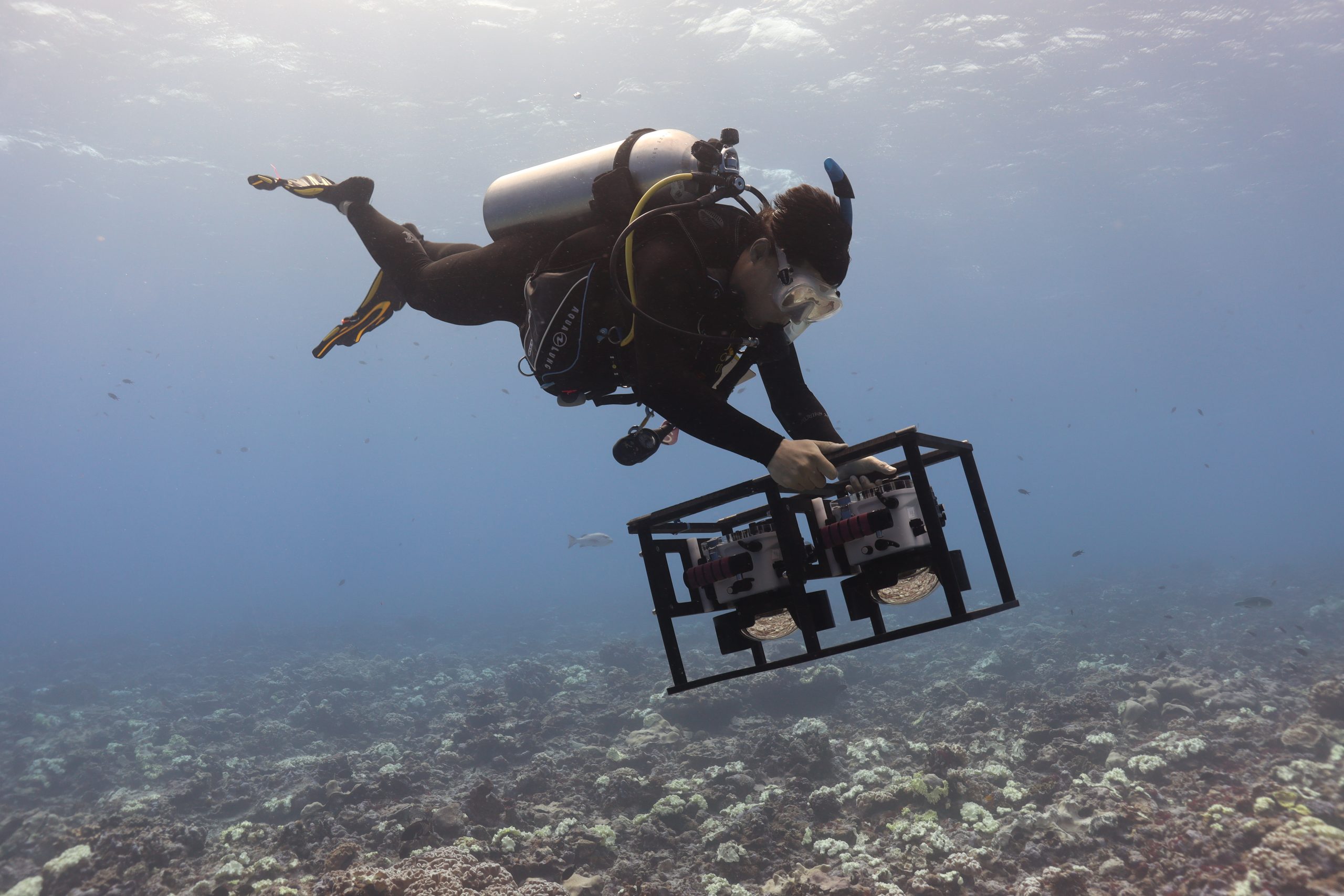

This underscores the need for more data on disease transmission, host species, their habitats and interactions with humans in order to take action at the root level. Unfortunately, we do not have much of this information, due to a lack of in-depth research and ignorance of this critical subject. The helplessness arising from this makes us fear forests and see them as reservoirs of unknown diseases. This view often results in alienating ourselves from forests or developing a tendency to destroy them in an attempt to prevent diseases.

One Health, a holistic approach

In 2023, a Nipah virus outbreak rattled Kerala—a small state on the western coast of India, nestled within the Western Ghats landscape. People’s opinions were divided by WhatsApp messages, with some arguing against the killing of bats and others fearing that bats could spread viral infections through fruits. But thanks to awareness campaigns by ecologists and the healthcare system, people as well as bats were saved.

It is important to consider the role of each stakeholder in developing preventive measures in the face of a public health emergency. People working in various fields, with strong scientific and sociological foundations and with experience in managing people on the ground have to work together. These include forest guards who identify and communicate potential human-wildlife interactions, health care workers, village council members, wildlife researchers, NGOs, virus research centres and various tiers of the government.

The One Health approach has recently gained global attention among public health and science professionals. The founding principle of One Health is to maintain the holistic and individual health of human society by conserving the health of natural ecosystems and their components. The success stories of this initiative from several nations underscore the importance of a broad, multi-dimensional approach.

Consider how Papua New Guinea, where 85 percent of the population lives in remote areas, welcomed the One Health approach. In association with the Tree Kangaroo Conservation Programme in the region, they implemented the “Healthy Village, Healthy Forest” programme, by recognising that sustainable environmental and public health management is only possible through practical solutions. The project focused on public health by ensuring basic government health facilities, enhancing village infrastructure and conducting peer group gatherings to make people aware of forest-health relationships, along with research activities. At present, the community is successfully producing sustainable coffee, while a dedicated, locally-owned area is reserved for conserving tree kangaroos by controlling the hunting pressure. This example demonstrates why our health cannot be viewed in isolation, nor that of wildlife or an ecosystem.

Are we ready on the ground?

What would your response be if a virus such as Nipah is increasingly reported in your locality? Would that response change if you were near the source of the disease? What if you were a health professional or a wildlife researcher? What if you were a forest watcher or the head of the Forest Department or the Minister of Forests, a police officer or the representative of a local body? Many people from different sections of society will be required to act during these situations, directly or indirectly.

Learning how to respond in such circumstances can help us grasp the intricacies of managing difficult situations. For example, insufficient and unreliable socio-scientific anecdotes become a major hindrance in tackling miscommunication and the spread of pseudoscientific news on zoonotic diseases. This is exacerbated by our limited capacity to communicate the scientific underpinnings of these issues efficiently. This can be only addressed by getting information directly from public health and ecology experts, and effectively communicating this to media specialists through science communicators, in consultation with other relevant stakeholders. In addition to this, the spread of false information can be prevented by a dedicated community of fact checkers at the regional levels.

Similarly, other aspects also need cooperation from people of various backgrounds across professional and social strata to tackle critical issues such as research funding, adoption of certain policies and management practices. While the international community is shifting its focus to these aspects, we have to ensure that the diverse dimensions of programmes like One Health, its different perspectives, possibilities and challenges need to be discussed with the public at the local scale. If these programmes confine themselves to the top of the social hierarchy and are technically difficult for common people to comprehend and participate in its functioning, it will not reach full potential at the bottom level.

Top-down or bottom-up?

As human health and forest health are tightly interconnected and their disconnectedness will result in cascading effects on us, we have to think about how we can ensure their intactness. One crucial point is to understand that we need a broad network of people and processes. This can only be achieved through brainstorming, research and policy making at multiple levels, starting from the local governments and other stakeholders who interact with forests and public health. In order to ensure bottom-level information is used in the health monitoring of local forests, animals and people, we will need the democratic involvement of people in the process, similar to the People’s Biodiversity Register Programme in India.

In this proposed process, we imagine people assessing their neighbourhood forests and human health using appropriate indices, such as biodiversity intactness, frequency of human-animal interactions, disease spillover chances and livestock-wild animal health to generate zoonoses probability maps. This can be facilitated by a spatial data collection system implemented at the state or regional levels, to which data is gathered at the finest level through people’s participation. This will help implement appropriate preventive measures at multiple levels, from local residential societies to the national level, with inputs of all stakeholders. We believe that such parallel top-down and bottom-up efforts can add momentum to global healthcare schemes like One Health, by linking some of the missing elements such as local-level information and participatory involvement of people from all strata.

In parallel, we also need a collective effort from all stakeholders to prevent interior forest degradation and to ensure the needs and rights of forest-dependent communities. Basic and applied research, supported and carried out by these stakeholders, will help us understand the deeper connections between forests and us. There must be scope for scientists, journalists and the public to talk to each other. That way, research findings can be effectively shared with the common people.

We need grassroot-level intervention and interactions where both decision-makers and common people can mutually benefit. Current discussions about nature and humanity often frame them as opposing forces, leading to binary thinking like forest vs. development or forest vs. urban dwellers. However, when we recognise that these dimensions can coexist only through trade-offs, we begin to understand just how deeply interconnected forests and humans truly are.

Further Reading:

Berrian A. M., M. Wilkes, K. Gilardi, W. Smith, P. A. Conrad, P. Z. Crook, J. Cullor et al. 2020. Developing a global One Health workforce: the “Rx One Health Summer Institute” approach. Ecohealth 17(2):222-232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-020-01481-0.

S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio, H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth et al. 2019. Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany.

Gadgil, M., P. R. Seshagiri Rao, G. Utkarsh, P. Pramod and A. Chhatre. 2000. New meanings for old knowledge: The people’s biodiversity registers program. Ecological Applications 10(5): 1307-1317.