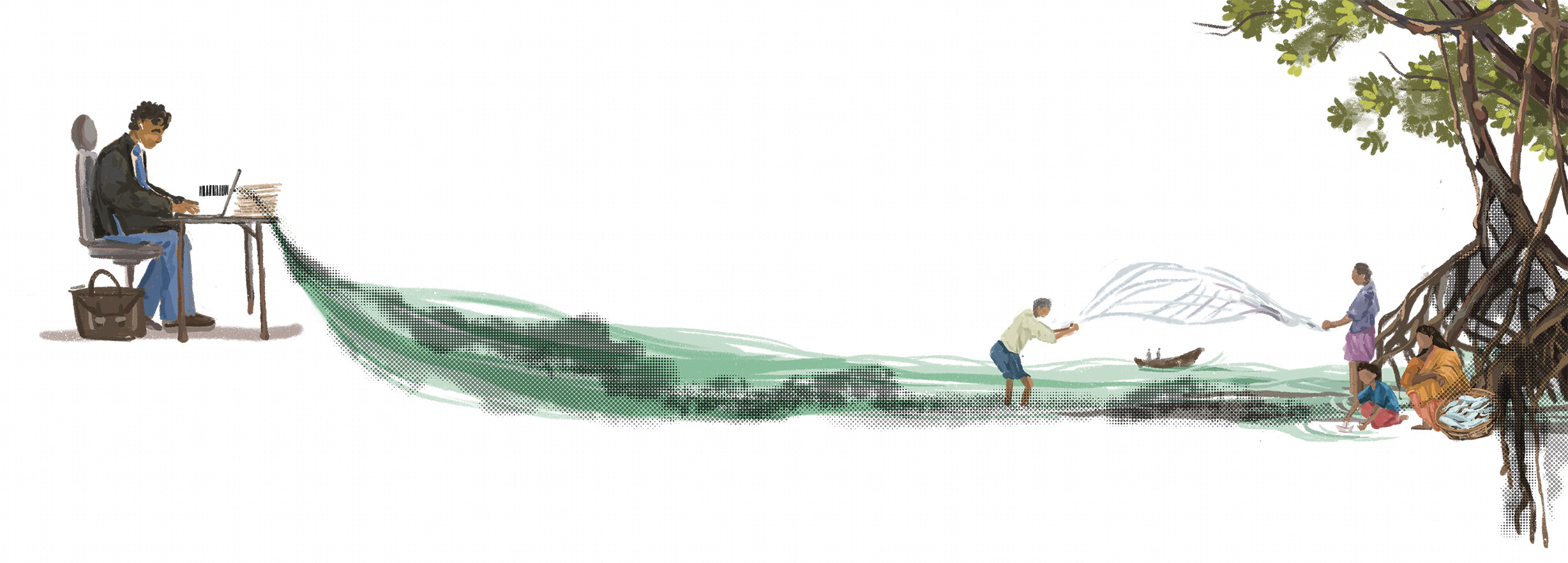

The Indian Ocean is hot stuff and one can’t say this enough; though being ‘hot’ is great until it’s not. Despite the fixing of maritime and territorial boundaries across its waters, Indian Ocean countries—lined up from African to Antipodean shores—remain connected, bustling multicultural sites, reminiscent of its ancient markets and trade routes. However, the imaginaries of souk-style easy cultural mobility and intermingling have given way to modern, specialised and elite gatherings, symposia, and seminars, where new inequalities and configurations replace the old. Legitimate mobility is no longer the defining feature of this part of the world; rather, it is distress migration from the deltaic and degraded ecosystems of the Indian Ocean that has gained notoriety in our times.

Information, strategy, and capital are traded and reproduced in exclusive networks of Indian Ocean blue economies. Subjects range from security, terrorism, tourism, ecology, mining, undersea exploration, carbon conservation, illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, disasters, and echoes of oceanic (dis)connected histories. The literal heating up of the Indian Ocean with rising global temperatures affects all of these sectors and conversations. Two aspects mark this new interest in climate discourse—there are few voices from where climate impacts the most, and there is little plain speak on the inconvenient truths of climate, such as differentiated responsibilities for climate impacts (or simply put: who is going to pay for saving the Indian Ocean).

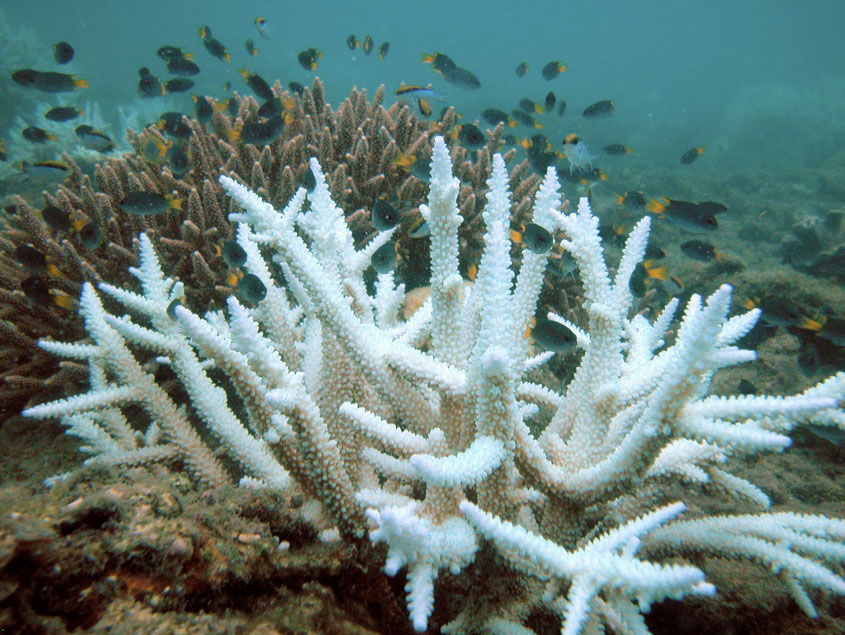

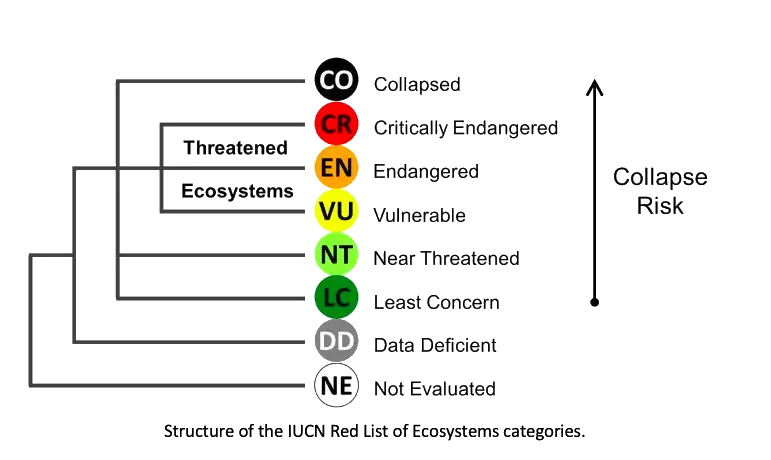

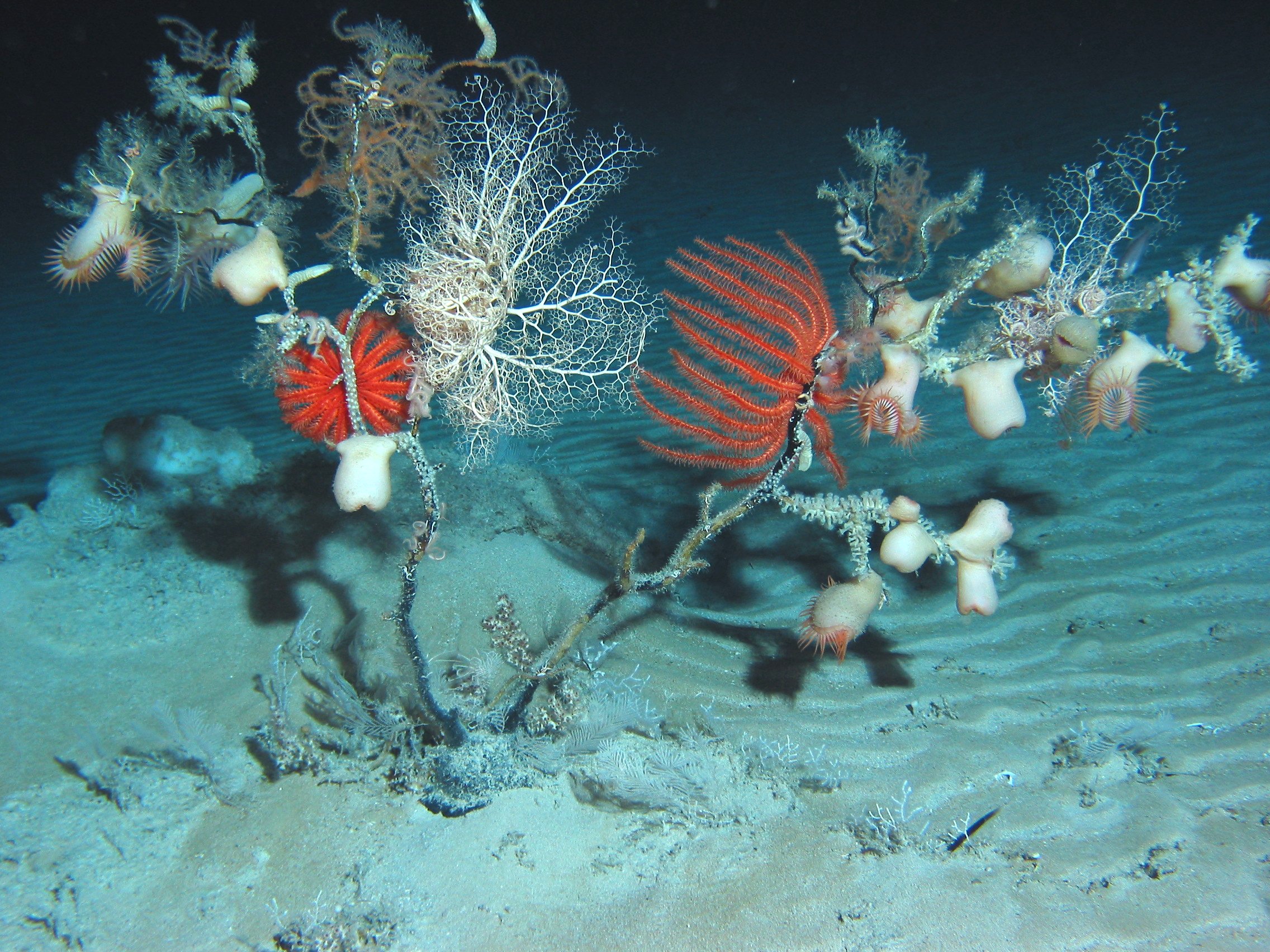

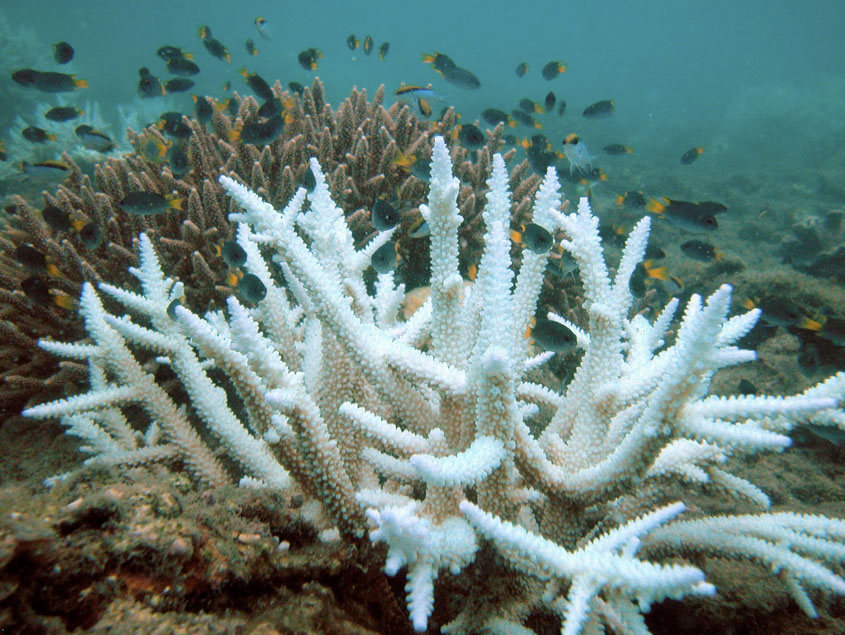

India is a good case in point. Marine systems receive limited attention and there is a need to mainstream ‘real’ issues into conversations about climate. The changing climate dynamic of the Indian Ocean entails a range of consequences from perturbations to the monsoon to cascading impacts on fisheries, agriculture, and the people dependent on them. Despite these looming threats, most of the recent press on the subject discusses little else other than extraction and harvesting resources under the blue economy umbrella. However, this extraction-focused mode is still in its early stages in some sectors, and there is potential for course correction even if we start now.

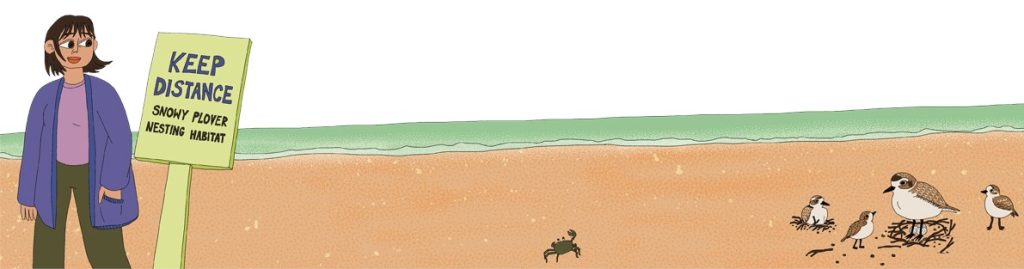

While countries should of course benefit from fish and other marine resources, planning needs to have an eye on future scenarios—not only in terms of continued availability of resources, but also in terms of inclusion, equity, and justice. Some geographies need special attention. In the Indian mainland, these can be states dealing with overfishing and distress migrations. On the other hand, with their large Exclusive Economic Zones and their remoteness, Indian island systems such as the Lakshadweep Islands and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands are more comparable to Small Island Developing States, which have their own peculiar set of challenges. These regions need new approaches that simultaneously integrate the blue economy with the challenges to blue justice.

One way to get climate action going is the arena of communication. Experts point to some unhealthy trends in this domain too, across the globe. On the one hand, there is little attention to solutions related to meaningful adaptation or feasible green energy transitions. On the other, an excessive focus on doomsday scenarios inures the general public into numbness, akin to doom scrolling or watching daily war reports on the news. Finally, there is a slow closing within the public sphere of marginal streams of knowledge that could transform on-the-ground and policy practices in controversial areas such as aquaculture, merely on account of communication capture by powerful actors.

Local governments in maritime nations struggle with the capacities to address the nuances of climate impacts in coastal areas. Preliminary enquiries in our areas of work in Odisha and Tamil Nadu, for instance, reveal inconsistent state funding for adaptation, absence of expertise within state Climate Cells, and an equation of climate adaptation with disaster management. Virtually none of the socio-technical infrastructure for climate in local and regional governments is sensitive to fisheries declines or marine ecosystem degradation (such as through marine plastics). The plethora of multinational projects that seek to address climate impacts largely rely on conventional disaster management techniques such as shoreline reinforcements, bunding, etc., that have proven poor track records. Other projects simply include plantations, often without attention to community tenurial arrangements over coastal commons.

Climate change strategies across the Indian Ocean lack a coastal-marine focus, specialist knowledge, and community engagement. Marine and coastal issues are often neglected in the larger narratives surrounding development, conservation, and climate change. Recentering coastal communities and ecosystems will require the building of capacities, but also investment of energy and diverse knowledge in strategic communications.

Several examples exist across civil society spaces, led by non-governmental organisations, universities, student groups, and individual actions. Some of these efforts are described in the articles in this issue. Not all efforts result in positive feedback for the system as a whole. The commercial interest in blue carbon sequestration against all odds, highlighted by Sisir Pradhan, is an example of negative implications of climate action. Surya Prabha and Sunil Santha’s work on seaweed farming draws attention to the difficulties inherent in crafting simplistic win-win solutions, where winners are few and losses multiple.

Climate change interventions also need funding and appropriate philanthropic engagement—and there is very little of that, at least for the oceans. When it comes to environmental issues, we find that marine issues receive only a fraction of the funding that terrestrial systems receive. Climate change with its imperceptible shifts (at least in its early years) as opposed to sudden visible catastrophes has been perceived as more of a benign risk, if at all. The few philanthropic dollars and rupees that actually do overcome climate deniers and their ilk often find their way into mitigation rather than adaptation projects.

Two oceans away in New York, each year Climate Week comes together as another bustling gathering. Drawing the world’s strongest advocates, innovators, and investors in climate action, the irony of its existence and performance did not escape us. In September 2024, we joined the ranks of participants who struggled to navigate Manhattan traffic and narrow streets across the dispersed venues of Climate Week. We entered and exited promising climate conversations, only to have the wind knocked out of us each time we encountered Manhattan’s glass towers of pure capital. Day 1 was a shocker, Day 3 almost comical, and by the end of the week, we longed for a space of less violent cognitive dissonance.

The Indian Ocean has been a space that wove in difference along with tumult. Whether in (climate) action or thought, between its unequal peoples and plans, the future imaginaries of the Indian Ocean must be guided by greater harmony and accord; features that make it an ocean that’s hot, for the right reasons.