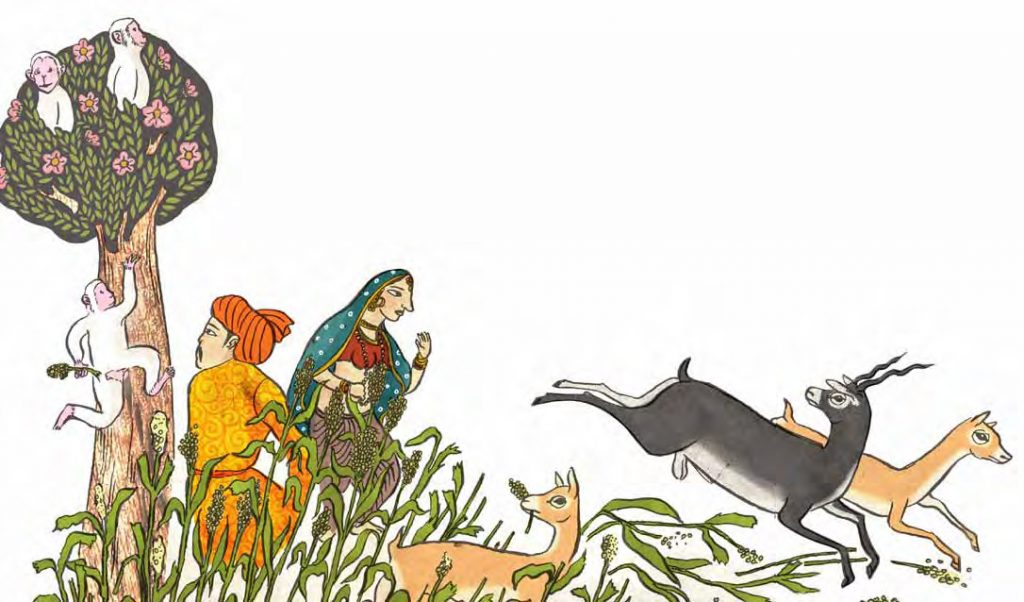

Once an integral part of her daily routine, it now has been weeks since she last wielded her hoe. “Things have changed since I hired a tractor and a neighbour sprays my fields with herbicides,” says Precious Banda, a farmer in Zambia. “Farming used to break my back, taking hundreds of hours, but life is easy now,” she adds. But she has also noticed changes around her farm. Most concerning for her: it has become difficult to find wild caterpillars and Bondwe (Amaranth leaves), which used to make her a delightful dish. Precious Banda’s story illustrates the situation of millions of farmers in the Global South.

Agricultural development is a top priority in much of the Global South. In Africa, for example, governments have ambitious goals for agricultural growth as part of the Comprehensive African Agricultural Development Programme (CAADP), with the aim to reduce poverty and hunger, which particularly affects farmers. But while agricultural development is necessary for improving livelihoods, it often clashes with biodiversity, which is rapidly declining worldwide. The Living Planet Index, representing over 20,000 populations of 4,392 species, shows an average decline in population size of 68 percent between 1970 and 2016. Scientists talk about a sixth mass extinction.

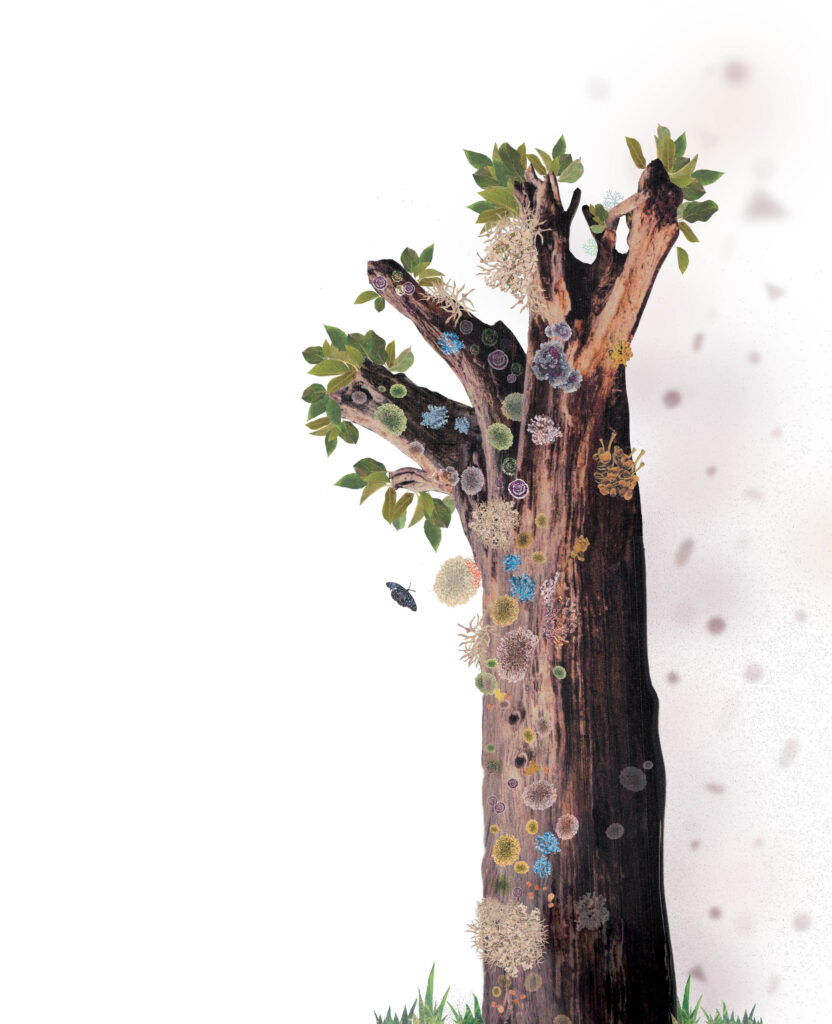

Losing the world’s remaining biodiversity could have dramatic effects on food security as it undermines ecosystem services such as pollination, soil formation, nutrient cycling, climate regulation, maintenance of water supplies, and pest and disease control. Biodiversity loss can also undermine farmers’ access to wild meat, honey, vegetables, fruits, tubers and nuts. In the case of Precious Banda, it is the loss of wild caterpillars and Bondwe that make her dishes less nutritious.

Agriculture affects biodiversity through both land expansion and intensification

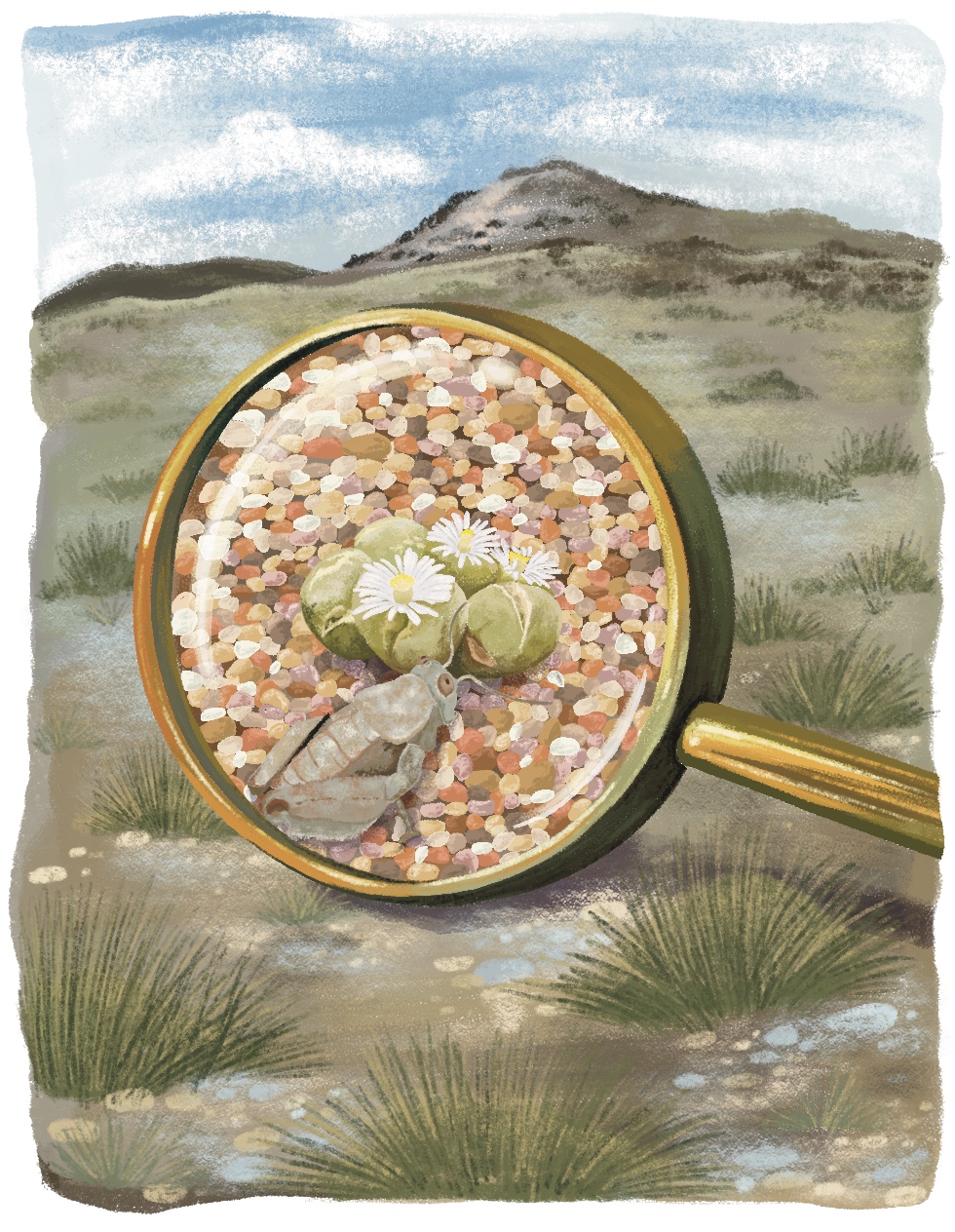

Agriculture affects biodiversity via two pathways: agricultural land expansion and intensification. In Africa, 75 percent of agricultural growth comes from the conversion of forests and savannahs into farmland, as a study in Science showed in 2021. Similar trends have been observed in other regions of the world. The loss and fragmentation of habitats threaten species that rely on large contiguous habitats for survival.

Intensification allows growing more food on existing land, sparing land for “wild” nature. As part of the Green Revolution, India tripled cereal production since the 1960s, while increasing farmland area by only six percent. In Africa, farmers still achieve only around 25 percent of their yield potential, according to a study by Wageningen University. However, intensification is often associated with greater use of agrochemicals such as pesticides and landscape simplification to ease the use of machinery.

The need to reconcile agriculture and biodiversity is gradually more recognised by researchers, policymakers, and farmers, among others. However, discussions on biodiversity-friendly agriculture focus mainly on conservation objectives and — to some degree — on reducing trade-offs with land productivity, which is important as low yields undermine land sparing. In contrast, the role of agricultural labour is often neglected. In a new paper in Biological Conservation, we argue that this is problematic given the heavy toil of agriculture for the world’s 550 million family farms, as exemplified by the story of Precious Banda. Ultimately, neglecting labour needs is not only bad for livelihoods but may also undermine the success of biodiversity conservation efforts. We, therefore, call for biodiversity-smart agriculture, which reconciles biodiversity conservation with not only land productivity but also labour needs.

Farmers strive to reduce the heavy burden of agriculture

Addressing agricultural labour issues is key to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Raising agricultural labour productivity can help to increase farmers’ income, thereby reducing poverty. Moreover, manual agriculture is burdensome. Cultivating one hectare of maize takes smallholder farmers close to 1200 hours, much of which is spent working with simple hand hoes in extreme heat and humidity (climate change will make this even worse).

“I can still feel it,” says Precious Banda as she recalls her farming experiences without tractors and herbicides. “I often felt bad but could not have done it without my children, sometimes they could not go to school,” she adds. The International Labour Organisation of the United Nations estimates that 70 percent of all child labour is in agriculture, affecting 112 million children. Furthermore, despite the prevailing notion of labour being abundant in the Global South, agricultural labour shortages have become increasingly common in many regions due to ageing, outmigration and structural transformation.

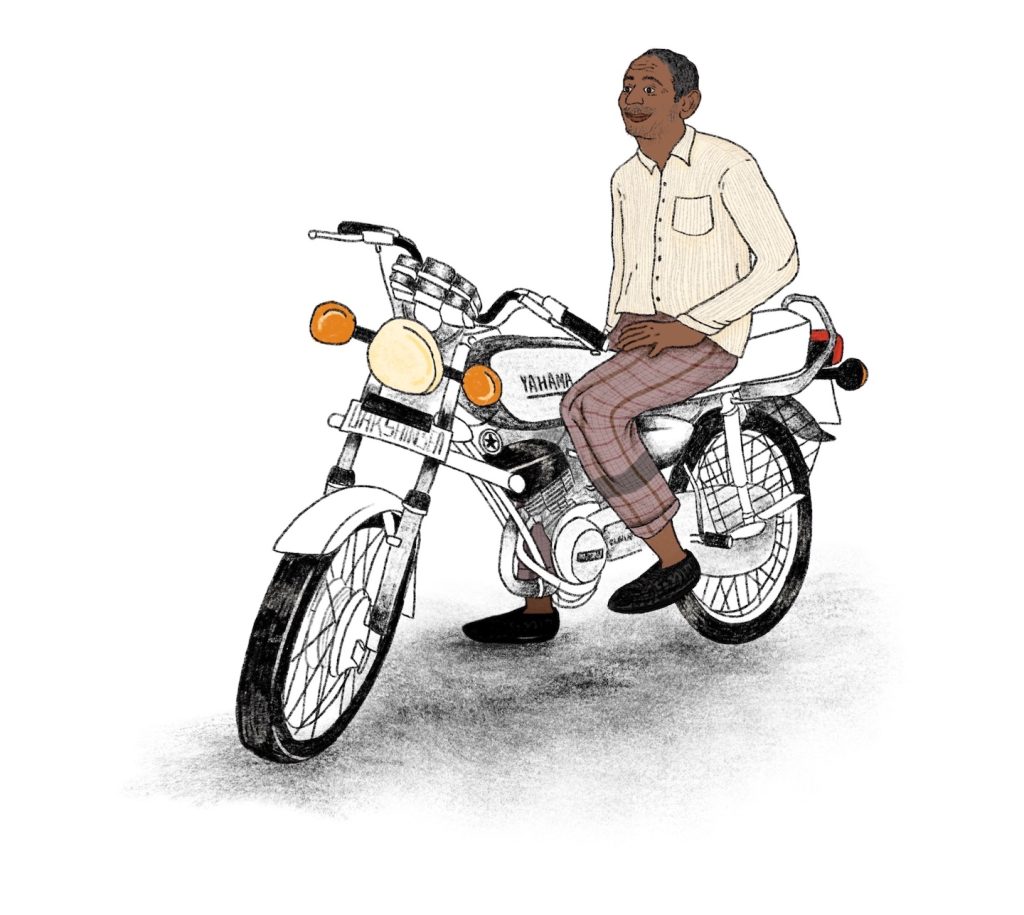

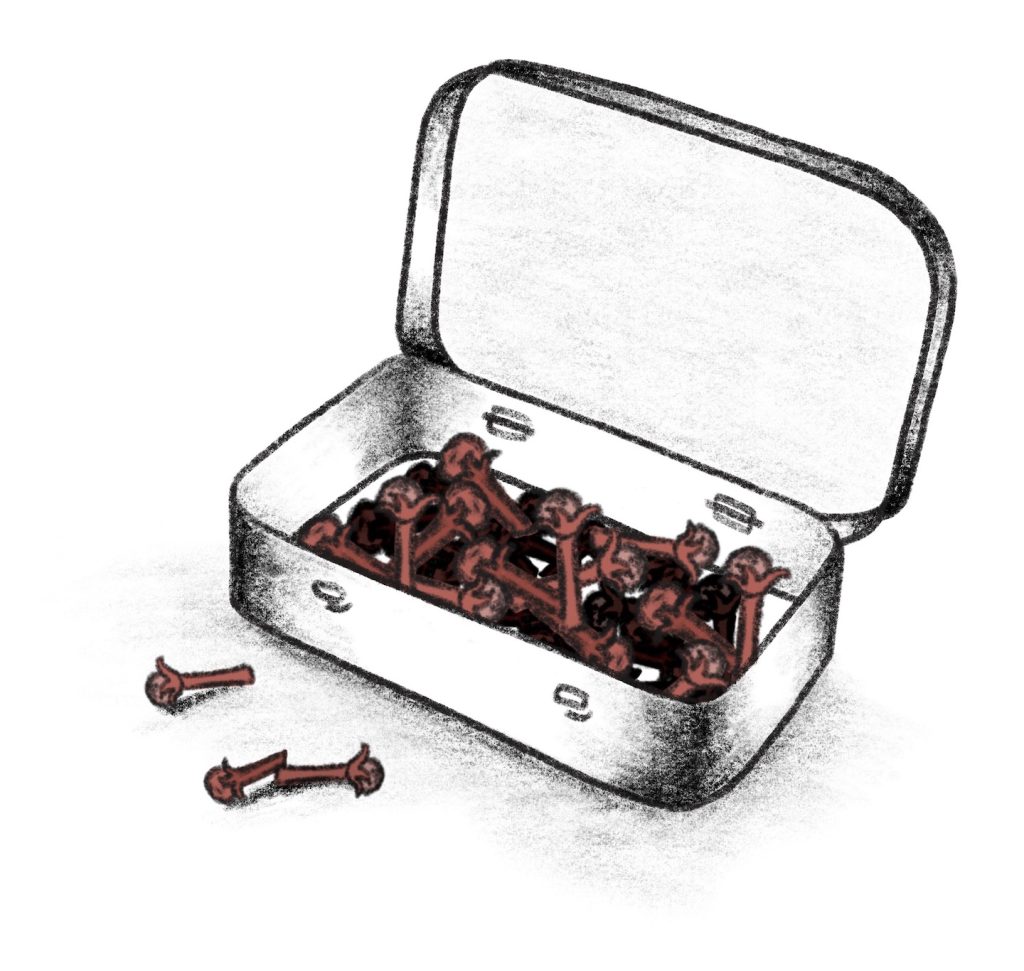

For many farmers, labour-saving technologies such as mechanisation and herbicides are therefore very appealing. In Zambia, farmers like Precious Banda, using tractors for land preparation need only 10 hours per ha — as compared to 226 for non-mechanised farmers, as a recent study in Food Policy has shown. In Mali, a study by Steven Haggblade and co-authors from Michigan State University shows that herbicides reduce weeding workloads by up to 90 percent. In Burkina Faso, William Moseley from Macalester College and Eliza Pessereau from the University of Wisconsin-Madison found that herbicides are often referred to as “mothers’ little helpers”. It is not surprising that the adoption of such technologies has accelerated rapidly across the Global South. Steven Haggblade and co-authors speak about a “herbicide revolution”.

Labour-saving technologies can negatively affect biodiversity

But while appealing and beneficial to farmers, such technologies can negatively affect biodiversity. The case study in Zambia suggests that tractors allow farmers to cultivate more land, which is good for them but bad for the African savannah. A comparative study in Benin, Kenya, Nigeria and Mali published in Agronomy for Sustainable Development suggests that mechanisation can lead to the removal of on-farm trees and hedges and the altering of plot sizes and shapes, leading to a loss of farm diversity and landscape mosaics.

Precious Banda experiences confirm this. “When I first approached the tractor owners, they sent me away,” says the Zambian farmer, “I had to pay someone to remove a couple of trees and stumps and now they are happy to serve my fields.” The same has already happened in much of Europe and the US, among others. Agrochemicals can also have negative effects. Pesticides can affect insect populations, soil biota, groundwater, lakes, and rivers, in particular when unregulated and when management practices are poor.

… and biodiversity-friendly practices can increase labour burdens

At the same time, many solutions to make agriculture more biodiversity-friendly are often met with resistance from farmers. Many organic or agroecological farming practices that would be good for local biodiversity are not adopted by farmers because they come with a high labour burden.

In China, intercropping is said to suffer from a “slow death” due to labour shortages. In a meta-analysis led by Sigrun Dahlin from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, planting basins were found to increase agricultural labour for land preparation by an astonishing 700 percent. A study in Zimbabwe by Leonard Rusinamhodzi, now with the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA), equates such solutions to “tinkering on the periphery”, as they create more problems than solutions for farmers. The increased labour burden of such technologies can be particularly pronounced for women.

Given these labour dynamics, it is not surprising that farmers typically adopt technologies and practices that ultimately lead them to a low-labour/low-biodiversity situation. This pattern has been observed across the world, first in the Global North but now increasingly in the Global South. In Indonesia, for example, our paper shows that farming systems have evolved toward oil palm monocultures with broadcast mechanical and chemical weed, pest and nutrient management, which are characterised by low labour intensity and high yields — but which are bad for biodiversity.

Biodiversity-smart solutions are good for nature and people

To successfully reconcile food production and biodiversity conservation, we need biodiversity-smart agriculture, which is high-yielding, requires little labour, and is biodiversity friendly. At the farm level, this requires efforts to reduce the biodiversity trade-offs associated with labour-saving technologies such as mechanisation and pesticides, and to reduce the labour trade-offs associated with biodiversity-friendly farming practices.

In parts of the Global North, one solution could be fleets of small agricultural robots, which help to overcome the yield penalties and labour requirements associated with agroecological farming, potentially leading to an ecological utopia as a recent article in Trends in Ecology and Evolution suggests.

In the Global South, less expensive solutions are needed. One potential solution is scale-appropriate mechanisation, where machines are adapted to farm size and not the other way around. This is because two-wheel and small four-wheel tractors are better suited to manoeu- vre around trees and hedges and other landscape features. In Arsi-Negele (Ethiopia), our paper shows that farming systems have evolved toward the low labour, low biodiversity, and high productivity scenario until the mid-1980s. But since then, they started to move to the low labour, high biodiversity, and high productivity scenario, through labour-saving technologies compatible with high biodiversity, as well as reforestation efforts.

With regard to pesticides, integrated pest management, which aims to reduce pesticide use with biological (e.g., crop rotations) and mechanical (e.g., precision sprayer) solutions could help to reduce trade-offs between yields, labour and biodiversity. In contrast, simply refraining from pesticides, would not be ideal as it decreases yields and therefore undermines land sparing. A recent review in the Annual Review of Resource Economics led by Eva-Marie Meemken, now at ETH Zürich, indicates that crop yields in organic farming are 19–25 percent lower than in conventional agriculture. Avoiding pesticides such as herbicides also comes with great labour needs, much of which is shouldered by women as discussed above.

Next to reducing the trade-offs of labour-saving technologies, such as mechanisation and pesticides, biodiversity-friendly measures are needed, including both production-integrated measures (e.g., patch cropping, intercropping) and set-aside measures (e.g., trees, hedges, flower strips). A recent study in Nature shows that tree islands can improve biodiversity in oil palm plantations in Indonesia, without compromising yields. But more research is needed to understand how such measures can be designed to minimise trade-offs regarding agricultural land and labour productivity.

In many cases, labour-saving technologies could help to increase the uptake of measures toward biodiversity conservation. For example, studies suggest that labour-saving mechanisation may be a missing link to a more widespread adoption of Conservation Agriculture, which is good for soil health and biodiversity. Similarly, smart mechanisation solutions could facilitate strip intercropping systems, which are labour-intensive in their manual form, and the management of hedges and flower strips.

Biodiversity-smart agricultural solutions reduce the trade-offs between socio-economic goals and biodiversity conservation for individual farmers, increasing the chances of adoption. This is key in the Global South, where many governments have few resources to otherwise compensate farmers for biodiversity-friendly farming. However, innovative certification or payments for ecosystem services schemes may still be needed where biodiversity conservation comes with more costs than benefits for individual farmers.

Ideally, such schemes should be designed to reward farmers for actual sustainability outcomes and not the practices pursued, and to take into account not only local but also global effects. Such farm-level solutions have to be accompanied by efforts at the landscape level, for example, land-use management to preserve biodiversity hotspots, habitat mosaics and patch connectivity. The case study from Ethiopia shows that multifunctional landscapes can be planned to “work for biodiversity and people”.

More efforts needed to scale up

Developing biodiversity-smart agricultural development requires paradigm shifts in both policymaking and research and development. For example, conservation ecologists must pay more attention to economic and social sustainability. Without explicitly accounting for labour issues, conservation efforts can hardly be successful. At the same time, agricultural scientists have to embrace multiple goals beyond yields.

Our paper shows that many solutions for biodiversity-smart agricultural development already exist. If they can be scaled, they can help us to feed the growing population, improve the livelihoods of millions, and protect the world’s remaining biodiversity conservation before it is too late. And for Precious Banda, the farmer in Zambia, they would allow her to continue her “easy life” as well as have her delightful dish with caterpillars and Bondwe.

Further Reading

Daum, T., F. Baudron, R. Birner, M. Qaim and I. Grass. 2023. Addressing agricultural labour issues is key to biodiversity-smart farming. Biological conservation 284: 110165.doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2023.110165.

Daum, T. 2021. Farm robots: ecological utopia or dystopia? Trends in ecology & evolution 36(9): 774-777. doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2021.06.002.