I was sitting in a taxi be squashed in between Malagasy people, carrying my huge sketchbook full of hand-drawn diagrams, when I felt I had gained a little personal victory on my PhD journey.

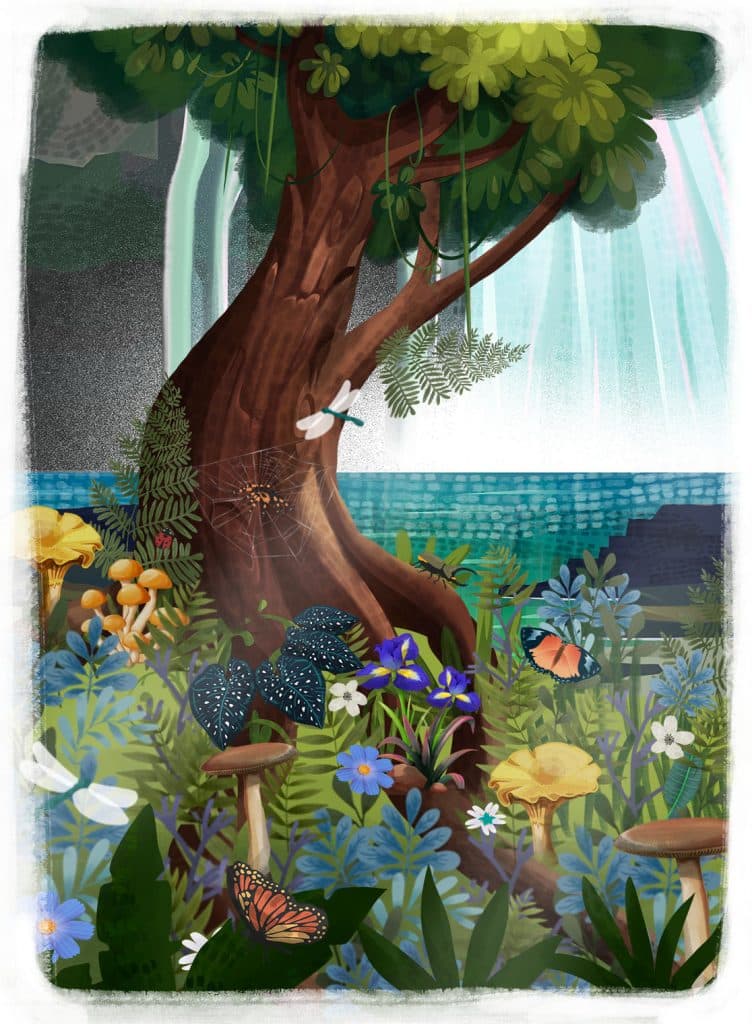

September 2019: It was my second time travelling to Madagascar— a world biodiversity hotspot and dream destiny for many—for my PhD research. I was excited by the possibilities ahead. My research consisted of interviewing practitioners from nature conservation organisations to hear their views on conservation education programmes. Despite the widespread belief that conservation education is a panacea for a sustainable future, the practitioners themselves often wonder whether their programmes have long-term impacts. In turn, I was trying to understand how these education programmes, which often target children living close to protected areas, influence the conservation of biodiversity.

The challenge

I decided to rent a room in the country’s capital Antananarivo, or just Tana as people call it, because most of the big conservation organisations were headquartered there. Doing research in Madagascar as a foreigner born in Barcelona and studying in Finland, required being respectful and striving to understand the cultural context as much as possible. Thus, I embraced the Malagasy lifestyle. And that included using public transport: taxi be. Taxi be are large minibuses that travel all around the city and, according to the Lonely Planet guide, “they are of limited use to travellers because of the difficulty to work out the route and where bus stops are”. But I was not put off by the challenge. Who said that the PhD journey would be an easy one anyway?

Increasing knowledge

It was one of my first afternoons in Tana, and I was having lunch with my colleague Rio in the city centre. I explained to him my determination to use taxi be, and that I had been searching for printed maps and online apps to increase my knowledge before getting on the first taxi be. Of course, these didn’t exist. Fortunately, Rio decided to take me under his wing. We walked together to one of the main bus stops where, during rush hour, you had to run to be the lucky person to squeeze into the already packed taxi be. After we managed to hop on one, Rio patiently explained:

“There are always two people working in the taxi be: the driver and the collector. The collector collects the standard fare of 500 Ariary (around €0.11) and he is the one shouting the final destination of the bus, so people know if it is convenient for them to get on”. Soon, we were approaching my home, so when the collector asked “Misy miala?” (Is there someone getting off?), Rio replied loudly: “Misy miala!” (Someone is getting off!).

Collaboration with others

For a while, I was only brave enough to attempt the same route I had done with Rio: from the city centre to home and vice-versa. I was scared of not knowing where to get on and off the bus, or which line to take. But as I started to schedule dates for my first interviews, I realized that I would never master the art of using taxi be unless I conquered my fear. I also realized that I couldn’t do it alone. Hence, every time an interview was scheduled, I would also ask for directions to get there by public transport.

Despite my careful planning, things often didn’t go as planned (this is exactly why problem solving is a skill you learn as a researcher). Tana is sprawled across two main hillsides and is full of steep and narrow streets, which translates into huge traffic jams. I am not a punctual person in my private life, but I wanted to arrive on time for my interviews. I would often leave home well before my meetings, only to end up sitting in a taxi be for two hours, stuck in a traffic jam. Sometimes, tired of sitting, I would get off and walk for a while, hoping that the traffic jam would disappear and that I could get an alternative taxi be. This meant, however, that I needed to ask for directions in my poor Malagasy. Yet, slowly, I started to understand how to get around the city.

Changing perspectives and cultural practices

In my interviews, I wanted to understand practitioners’ assumptions about the role of education in conservation. This turned out to be a difficult task because for many of the interviewees, it was their first time reflecting on the linkages between activities, outcomes, and impacts. Due to this, I decided to use a participatory research method: instead of me asking questions and writing notes, we would draw. Well, maybe not exactly draw, but we would create diagrams to identify the pathways that connect their education programmes with conservation goals. That is how I ended up buying a huge sketchbook that I carried along to the interviews.

Despite being born in the Mediterranean culture, my perception of personal space had been strongly transformed after years of living in Finland. Personal space is essential for Finns. Often, on Finnish buses, people would rather leave a seat unoccupied than sit next to a stranger, to allow for personal space. That was absolutely not the case in Madagascar. Taxi be were often packed with people, and even the aisle would be transformed into a seat by placing a wooden plank across the seats on either side. The first few times, I felt uncomfortable and ashamed when entering with my huge sketchbook, silently apologising to others for taking up so much space. But, soon my perspective changed as I understood that the Malagasy idea of personal space was completely different. After this, I embraced—and somehow enjoyed—the trips being squashed between others.

Diversifying options

I was starting to feel confident about commuting by taxi be when I decided to venture outside the capital. Some of my interviewees were from smaller organisations that worked only in certain regions of Madagascar. For one of those visits, I travelled overnight by taxi brouse (minibuses that travel around the country) to the coastal city of Tamatave. On arriving, I received a call from Tsiry, the practitioner I wanted to interview. He asked if we could meet at their education centre, located 30 minutes outside the city. I thought to myself: If I can use public transport in Tana, why not in Tamatave? I left with my backpack and my big sketchbook without hesitation. After being directed to different bus stations, I managed to get the right bus, arriving at my destination exactly at lunchtime. Tsiry and their colleagues invited me to share lunch with them.

We conducted the interview after the meal. Then, Tsiry offered to give me a lift back to Tamatave on his motorbike. I happily accepted because I was exhausted, but I also thought it would be great to have another new experience under my belt. However, the motorbike suddenly stopped as we were riding. “How strange. This has never happened before,” Tsiry said, as he tried to fix it. No luck. Someone passing by stopped and gave it a shot too. Still no luck. Suddenly, a cyclo-pousse (a rickshaw pulled by a cyclist) came to a halt and offered to take us. Tsiry and I looked at each other—could a cyclist carry a motorbike? It was the moment to find out. We put the motorbike on top of the cyclo-pousse and clambered into the rickshaw ourselves. To our surprise, we slowly managed to reach the city. Tsiry repeated once again, laughing: “This has never happened before.”

Leaders of change

It was one of my last days in Tana. For two months, I had met and been inspired by passionate conservation practitioners working across the country. I was sitting in a taxi be, squashed in between Malagasy people, feeling proud of my own learning process with public transport. A whole range of strategies had helped me achieve my goal: from increasing my knowledge thanks to Rio, to asking others for directions, to changing my perspective of personal space and diversifying my transportation options.

In a similar way, the results of my research also showed that there isn’t a single way to achieve positive change through education, but rather that practitioners had different views on how the change was brought about. Five pathways of change emerged on the role of education in conservation across the 15 organisations I interviewed. For some, it was about increasing knowledge. Others stressed the importance of building an emotional connection to nature and changing certain traditional cultural practices. Others believed that change should happen at the community and societal level, highlighting the role of collaboration amongst stakeholders. And a few others emphasized that education approaches need to be accompanied by other structural solutions, such as access to alternative livelihoods and policy changes. Finally, many highlighted the importance of fostering future leaders: youth who would have agency over their natural resources.

It was time for farewells, and I was feeling a mix of emotions. I felt privileged to have met all those practitioners who were leaders of change themselves. People like my friend Lova, who worked persistently to implement conservation education programmes with boundless energy, despite the lack of time and resources. At the same time, I was doubtful about the practical implications of my research. It had not answered the question about whether education has an impact on conservation. But complex problems never have a straightforward solution. Yet, reflecting on the pathways of change was probably a first step towards a more comprehensive evaluation, and to be able to design transformative interventions. For years to come, education will probably remain a cornerstone of conservation initiatives. But, what if the end goal went beyond biodiversity conservation? What if education could also support and celebrate the richness of cultural diversity? What would those education programmes look like? Unfortunately, my time in Madagascar was up, so those would remain questions to explore in the future.

Further Reading

Brias-Guinart, A., K. Korhonen-Kurki and M. Cabeza. 2022. Typifying conservation practitioners’ views on the role of education. Conservation biology 36(4): e13893. doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13893.