Click here to read this article in Português.

DISCOVERY OF THE FAVEIRO

In Minas Gerais, a southeast Brazilian state known for its mineral wealth, there is another kind of natural treasure, which is still hidden: the faveiro-de-wilson tree (Dimorphandra wilsonii) from the legume family. Its story probably started a long time ago, but the species was known to science only in 1968, when a woodsman, Wilson Nascimento, came across a few individuals of the species in the Paraopeba municipality. The following year, this tree was described by Dr. Carlos Rizzini of the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden Research Institute, who had employed the woodsman as a research assistant. The scientific as well as common name of the species honour Mr. Wilson, who passed away shortly after the discovery.

It is curious how such a large tree species found in the vicinity of a metropolis was discovered so late. It was assumed that the species was never very abundant in nature. 15 years later, in 1984, Dr. Rizzini returned to that region and counted only 18 individuals of the species, both in Paraopeba as well as in the neighbouring municipality, Caetanópolis. Since he had encountered so few individuals, he believed that this species could be at risk of extinction.

Following this, the faveiro-de-wilson was forgotten about until 2003, when it was ‘rediscovered’ by researchers from the Parks and Zoo-Botanical Foundation of Belo Horizonte’s Botanic Garden. They visited the Paraopeba and Caetanópolis municipalities, where, in the midst of extended pastures of the invasive alien grass Urochloa decumbens (also known by its synonym Brachiaria or “braquiária” in Portuguese), they spotted a dozen old and peculiar faveiro-de-wilson trees.

This encounter led to several questions: Is the species rare? Does it only occur here? Is it facing extinction? What do we know about its biology and ecology? To answer these questions, the researchers began seed collection, nursery reproduction, and studies on phenology and population genetics. On realising that it was a rare and poorly documented species, finding more individuals and protecting this mysterious species became their priority. Committed to finding more faveiro-de-wilson individuals, the researchers ignored all the discouragement aimed at their attempts to protect a species considered a “lost cause”. They decided to carry out direct searches throughout the state of Minas Gerais. To help with this difficult task, they had an idea: creating and distributing “wanted” posters and leaflets with information about and photos of the species, as well as the team’s contact details. And thus, the long search for the faveiro-de-wilson began.

THE TREASURE HUNT

The search resembled a treasure hunt, except without a map for guidance. Outreach materials in hand, the group of researchers went to “hunt” for the faveiro-de-wilson, putting up posters everywhere and approaching local people, mostly in the country-side. They handed out leaflets with images and passed around samples of faveiro’s leaves, fruits, and seeds, which could be touched and smelled. The team asked if people knew the species and could help them locate individuals. Those who had the closest contact with nature and were interested in collaborating became special partners, who were later referred to as “faveiro hunters”.

The absence of a general mechanism to protect the species in its natural habitat led to the creation of a state decree in 2004, which declared a ban on the logging and exploitation of the faveiro-de-wilson in Minas Gerais. In 2006, the conservation status of the species was assessed and subsequently published in the IUCN Global Red List’s “Critically Endangered” category. Another couple of years later, the faveiro-de-wilson was also included in the Minas Gerais and Brazilian Official Red Lists.

In the following years, with logistical support from the State Forest Institute (IEF, acronym in Portuguese) and sponsorship from a cement company and a non-governmental organisation, the tree searches were reinforced and the research was extended to include physiology and reproductive biology. Other activities were also initiated at the same time, including the reintroduction of the species in suitable habitats and spreading environmental awareness through meetings, chats, and presentations in schools, at public squares, and other places. Thus, a simple project became the Faveiro-de-Wilson Conservation Programme, whose work was mainly focused in the central region of Minas Gerais, in the transition or ecotone zone between two biodiversity hotspots: the Cerrado (a vast tropical savannah) and the Atlantic Forest.

Although the conservation programme was focussed on a single species—the faveiro-de-wilson (D. wilsonii)—researchers stumbled upon another morphologically similar species during their surveys in the region. The faveiro-da-mata (Dimorphandra exaltata), native to the Atlantic Forest, is likewise rare and little investigated. Until then, it was known only from herbarium records collected in the eastern region of Minas Gerais and in some municipalities in the states of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. This was the first time that they observed it in the central region of Minas Gerais and such a discovery would bring more challenges and surprises.

CREATING A CONSERVATION ACTION PLAN

Thanks to community involvement, the treasure hunt for faveiro-de-wilson yielded good results. Up until 2013, 219 adult individuals had been recorded in 16 municipalities in the central region of Minas Gerais. They were able to show that the species was endemic to this region. With all the data and information gathered during the surveys, there was an impetus to create a Conservation Action Plan (CAP) for the species—Faveiro-de-Wilson CAP. This was done in partnership with the Brazilian National Centre for Plant Conservation of the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden Research Institute (CNCFlora/JBRJ, acronym in Portuguese) and involved 30 stakeholders from 10 institutions.

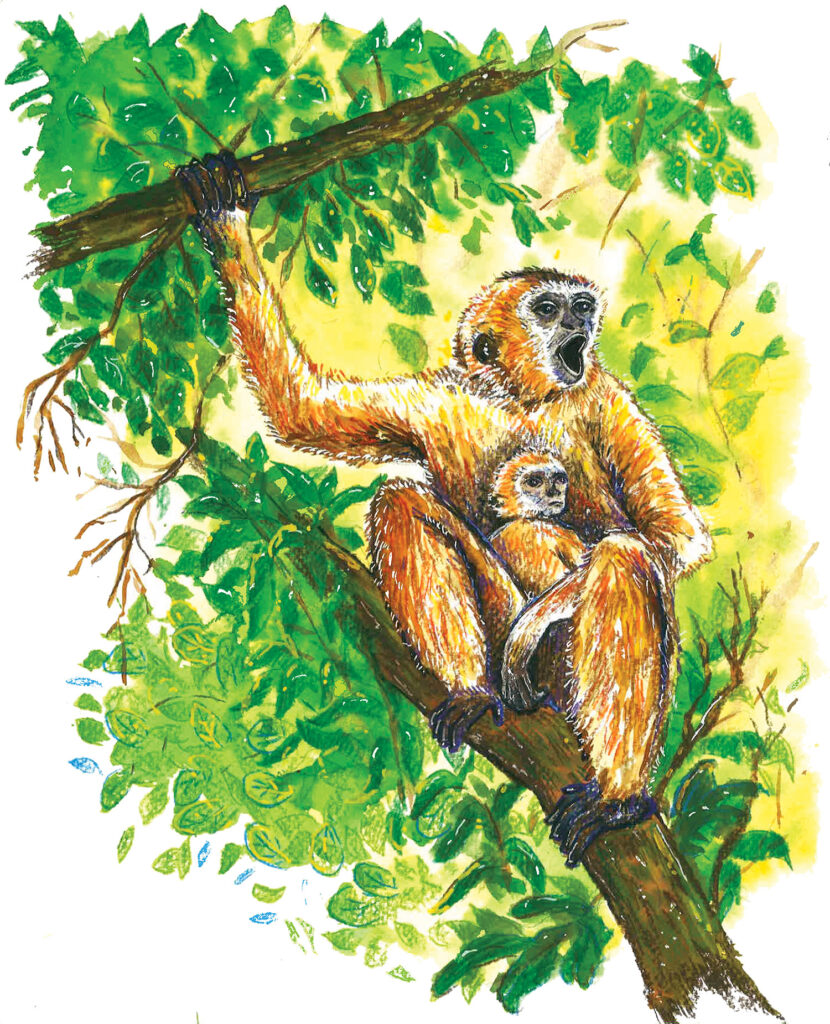

Five years later, in 2020, most of the conservation actions were implemented/executed by the stakeholders involved in the Faveiro-de-Wilson CAP. It was noted that faveiro-de-wilson and faveiro-da-mata are not used for commercial purposes. However, their pods/favas, although dry, are palatable and nutritious for animals, including wild species (e.g. tapir, paca, deer, cotia, and macaw) as well as cattle and horses, who also help disperse the seeds. Moreover, since the pods fall in the period when the pastures are dry, they are beneficial for farmers whose cattle feed on them. This fact has been used to advocate for the conservation of this species. However, although both species produce many fruits and seeds, the recruitment is low, and growth is slow and uneven. Additionally, the young plants have to compete with the aggressive alien grass, braquiária, as well as survive being trampled by cattle and predated on by insects, all of which leads to many losses, including in reintroduction attempts.

TRACING THE ORIGIN OF THE FAVEIRO

From the start, a genetic comparison was sought between the faveiro-de-wilson and the faveiro-do-campo (Dimorphandra mollis), a non-threatened and common species in the Cerrado with a wide distribution in Brazil. But after faveiro-da-mata was discovered where the researchers knew that the three species converged, they were all considered in the genetic studies performed by the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG).

This led to a surprising discovery in 2019: the faveiro-de-wilson is a probable natural hybrid of faveiro-da-mata and faveiro-do-campo!

Such a revelation prompted researchers to make several adjustments along the way. For example, the illustrated educational booklet, which was being written for schools, ranchers, faveiro hunters, stakeholders and other partners, was published in 2020 under the title “Preserving the Rare Faveiros”, in order to also include faveiro-da-mata and faveiro-do-campo.

A milestone was reached in 2020, with a total of441 adult faveiro-de- wilson trees being georeferenced and marked in 24 municipalities. However, none of these trees were found inside Protected Areas and the vast majority of them are located in deforested landscapes. This makes the conservation of the species more challenging.

Additionally, 451 individuals of faveiro-da-mata were also found, georeferenced, and marked in the same region. For both species, the researchers observed that the main cause for drastic reduction was not any specific uses of the plants, but simply the destruction of their habitat. Based on this new information and expanding knowledge, CNCFlora/JBRJ has now re-evalua- ted the faveiro-de-wilson and down-listed the species from Critically Endangered to Endangered, also including the faveiro-da-mata in the same category. Both species assessments have been submitted and the faveiro-da-mata assessment has already been published on the IUCN Global Red List.

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

CNCFlora/JBRJ recently joined forces with national and international institutions (e.g. IUCN SSC CSE-Brazil and CEPF) to develop the Conservation Action Plan for Threatened Faveiros Species (Dimorphandra), which includes faveiro-de-wilson and faveiro-da-mata as targets species, and faveiro-do-campo as beneficiary species. This made it possible to redefine the objectives and priority actions, as well as to expand the efforts undertaken for the conservation and recovery of their populations. This change was very important because the Cerrado and the Atlantic Forest, where these species occur, are under severe pressure from agricultural expansion and livestock rearing. Thus, conservation efforts from multiple angles are needed in order to succeed. Moreover, these efforts to restore and protect the faveiros and their habitat require national and international collaboration among stakeholders to drive investment and conservation outcomes.

Thousands of people have been involved in the conservation programme over the years—from different sectors (public, private, and non-governmental) and from different cities. This includes school students, local communities, faveiro hunters, the fire brigade, and rural landowners, who safeguard the two rare faveiros on their properties with great pride. It is also worth mentioning that in 2015, the Faveiro-de- Wilson Conservation Programme was awarded the National Biodiversity Award for the best Brazilian nature conservation initiative from the Ministry of Environment under the public service category. Through our joint efforts, we hope to continue expanding our work to protect these peculiar faveiros trees in a region which should be remembered not only for its mineral resources, but also its green treasures.

This article has been translated into Portuguese and is available in the online version of the issue (www.currentconservation.org/issues/)

Further Reading

Fernandes, F. M., A. C. R. Pereira, A. C. Roque and S. C. Fonseca, S.C. 2020. Preservando os raros faveiros. Belo Horizonte: Fundação de Parques Municipais e Zoobotânica.

Fernandes, F. M. and J. O. Rego.2014. Dimorphandra wilsonii Rizzini (Fabaceae): Distribution, habitat and conservation status. Acta Botanica Brasilica 28: 434–444. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-33062014abb3409.

Muniz, A. C., J. P. Lemos-Filho, H. A. Souza, R. C. Marinho, R. S. Buzatti, M. Heuertz and M. B. Lovato. 2020. The protected tree Dimorphandra wilsonii (Fabaceae) is a population of inter-specific hybrids: Recommendations for conservation in the Brazilian Cerrado/Atlantic Forest ecotone. Annals of botany 126: 191–203.

https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcaa066.